For a broader take, consider looking at its Wikipedia entry in another language — particularly in a language culturally closer to the subject. You’ll open yourself up to a world of perspectives, says Daniel M. Russell, online search expert and Google research scientist.

This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from someone in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

The other day, I was talking with a friend about Leonardo da Vinci, that great polymath of the Italian Renaissance. As we talked about his artistic output and his legacy, it seems there’s some debate about whether he was the greatest artist of all time or merely a worthy competitor to Michelangelo and other contemporaries. But how can one get a sense for the man some 500 years later?

Being a research scientist who specializes in search engines, my thoughts turned to how I would research this online. Is there a way to get a sense of the legacy of a famous person? What would that mean? To capture my curiosity, I wrote down this research question.

How can you get a good sense for different cultural interpretations of an idea — in particular, for Leonardo and Michelangelo? Is there a way to do this with online research?

It’s a fairly open-ended question and one you can spend a long time answering. A historian may say you need to read extensively about a person’s life and work, but having the time to devote to a single issue is a bit of a luxury.

I wondered: “What about Wikipedia? How could we use it more effectively?” There’s a lot of debate about how accurate and reliable Wikipedia is, but I find that for many topics, it’s fairly reliable. This is especially true once you know a bit about how to do online research there. If you’re not already in Wikipedia, the fastest way to search is to add the context term “Wikipedia” to your search query. The results will be primarily from Wikipedia and Wikimedia.

If the topic you’re searching is fairly rich, you’ll see an indented set of items. These are “deep links” into a specific section of the article; click on them to jump there.

If you want to search for, say, Leonardo da Vinci only within Wikipedia, use the site: operator (go to google and type in “site: Wikipedia Leonardo da Vinci”). The results will be limited to Wikipedia.

To answer my research question, I found that doing a site search with the two artists’ names (type in “site: Wikipedia.org Leonardo da Vinci Michelangelo”) brought up Wikipedia articles where both are mentioned. It was a great way for me to quickly learn about their connections. While they’re usually named together, Leonardo and Michelangelo just barely worked at the same time. Leonardo was already 23 when Michelangelo was born, and he was artistically active for 37 years. Michelangelo began his professional career when he was 17 and was creative for around 52 years, although often in sculpture and architecture rather than painting.

You’ve probably been using Wikipedia for a while, but you may not have noticed there are entire other worlds of information in it to examine. Call up the Wikipedia entry about “cats,” and on the left hand side you’ll see a column labeled “Languages.”

Wikipedia comes in 287 languages, with more being added every day). Those links on the left point to the equivalent article in another language. A gold star next to a language link means that this is a featured article — and the editors are indicating that this article is of exceptionally high quality and often used as an example for other Wikipedia authors. It’s always worth checking out articles in other languages that have a star.

Although you may have known about the other languages, what you might not have realized is it’s not the same article that’s been translated into all the world’s different languages. Even fairly straightforward articles can be different, and they’re well worth looking at for comparison purposes. After clicking on a language, you can then use Google Translate to convert the article into a language you do read.

Look at the “contents” of the “cat” article in English and the Spanish-language “cat” article (when I did, I translated it into English to read). You can find the contents located directly below the introductory section. Note how different they are.

For some reason, the Spanish “cat” entry goes into much greater detail about cat diseases (there are 12 subsections) than the English entry (where it’s covered in 1 subsection). I have no idea why. The Spanish entry also covers the effects of secondhand tobacco smoke on the rate of oral cancers among cats. (Yes, secondhand smoke is bad for cats, too.) Are the cats in Spanish-speaking countries more likely to get sick?

Now the topic of “cat” is fairly noncontroversial. But when you compare topics that are culturally, historically or politically loaded, you’ll find that the differences become even greater. (The Wikipedia editorial board locks down the most controversial articles that attract a great deal of vandalism. The entry on “Hilary Clinton” is one such example — ordinary people can’t edit it; only fairly trusted Wikipedia editors can.)

As you can see, reading entries in different languages can give you, the online researcher, a set of different perspectives. Now let’s return to my original question of comparing Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Take a look at the Italian-language article and the English-language article (I translated the former to read it). It makes sense that the Italian entry would be more comprehensive than the English entry, but it’s also interesting to read the different choices that the editors in each language made about what to cover and in what depth. For example, just the section on the personal life of Leonardo in the Italian article is longer (12,000-plus words) than the entire article about Leonardo in English (8,000-plus words).

These differences become especially obvious when you look at the Italian-language article about Michelangelo’s painting Battle of Cascina — it’s a detailed and well-documented article. Meanwhile, the English-language entry is barely a few hundred words. These kinds of cross-cultural comparisons are fascinating to make, and they’re potentially valuable when doing research. If you ever find yourself frustrated by the lack of depth of the Wikipedia article in your own language, try another language — ideally one that’s closer to home for the material.

After noticing that I was bringing up multiple side-by-side browser windows to compare Wikipedia articles in different languages, I wondered: “Could I find an online tool that would help me do this?” A rule of thumb I use when I find myself doing something repeatedly is to look for a tool to help with the task.

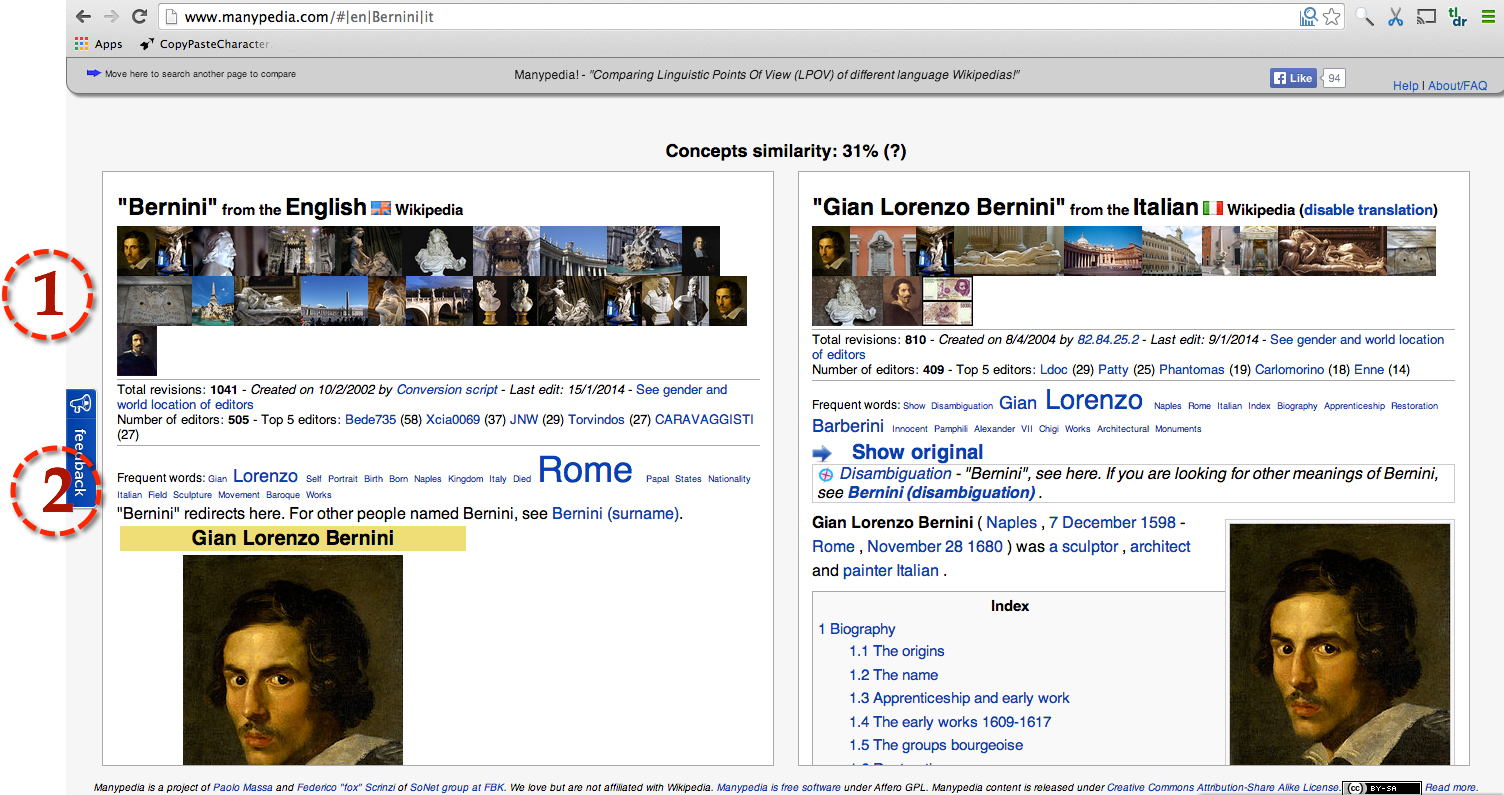

Manypedia.com does exactly that. It lets you look up a single topic and then look at the Wikipedia articles from different languages alongside each other. For example, when I look up the Italian sculptor Gian Bernini (who was born just 79 years after Leonardo died), I can see the English- and Italian-language (shown below, in translation) entries at the same time.

I’ve added two numbers to the above screen capture to point out two interesting features in the Manypedia interface:

(1) is the list of all the images from the Wikipedia article (each shown as a small thumbnail). Notice how the list of pictures is very different between the two articles. Bernini’s great work The Hermaphrodite isn’t mentioned in the English article, yet it shows up in the Italian article. You can spot this immediately by observing the differences in the image summaries.

(2) is a kind of word cloud (the font size indicates how often a word appears in the article) just below the image summary for the Wikipedia entries. Again, a quick scan shows significant differences between the articles. In the Italian article, “Lorenzo” (it appears 47 times) and “Barberini” (14 times) are most important, and in the English entry, “Rome” (106 times) and “Lorenzo” (47 times) dominate.

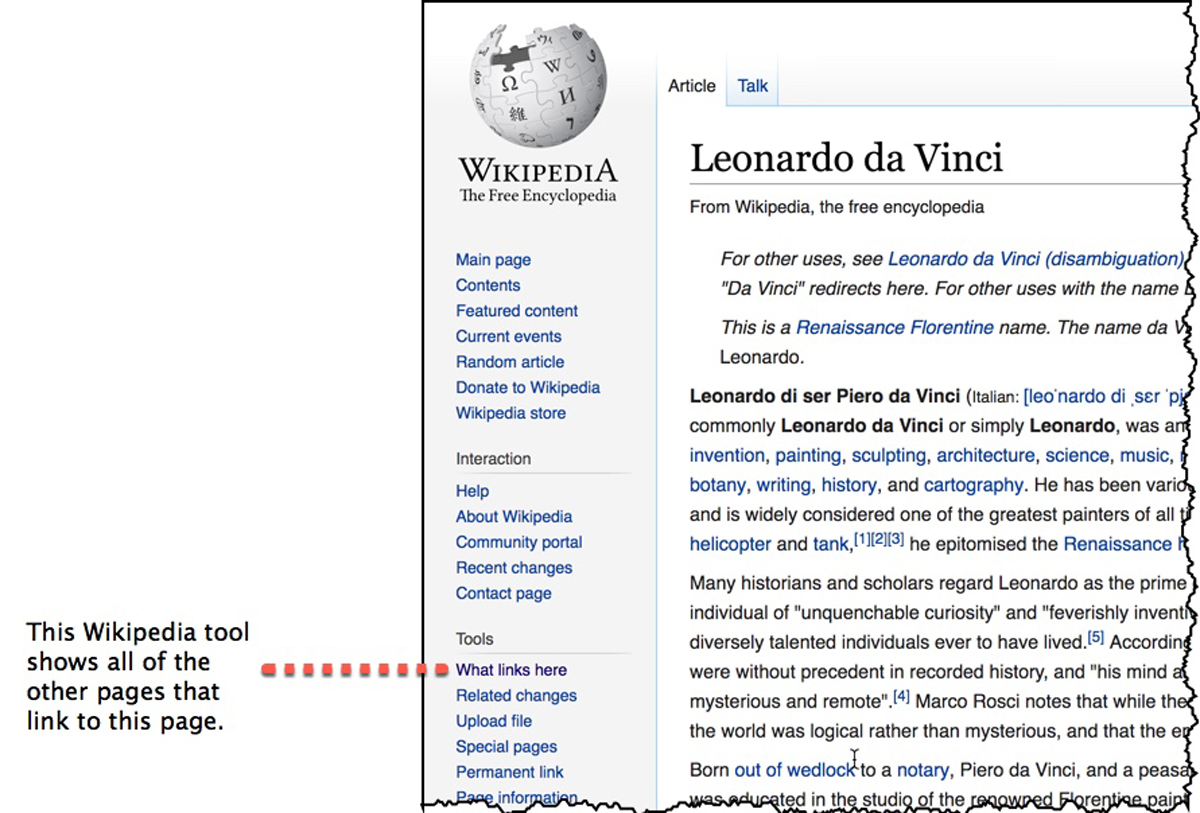

Wikipedia also has another clever method for giving context that goes beyond the ordinary. The Wikipedia tool “What links here” appears in the left-hand list of links on a typical Wikipedia page (below).

When you click on “What links here,” you’ll get a long list of all the other Wikipedia pages that have a link to this one. In this case, I was able to see all the other Wikipedia pages that link to Leonardo’s page.

Scanning that list gave me an overview of the other people, places, times, projects and influences that somehow connect to Leonardo. It’s as though someone pulled out all the key concepts from Leonardo’s article and presented them to me as a list. I often look at “what links here” when I’m trying to get a sense of what connections exist between my main topic and the rest of the world.

For instance, reading through the list of pages that link to “Leonardo da Vinci,” I can see there’s a connection to Cesare Borgia, a well-known person of the age. When you roll over that link, a pop-up summary appears. If it looks intriguing, you can open this article in a new browser tab.

I’ll end with a recap of my three research lessons about Wikipedia.

1. Wikipedia comes in multiple languages.

When you’re looking up an article on a topic that is highly culturally specific, be sure to look in that language as well. Famous people, places and things tend to have longer and more detailed descriptions in the language that they’re associated with.

2. Pay attention to Wikipedia stars.

The gold stars mark articles that are especially well written and complete and have good references. If you’re looking at an article that seems a bit sketchy or lightweight, look for the same article in another language. If it’s got a star, there’s a good chance that reading the starred article (in translation) will be more useful than the inadequate article you were reading.

3. “What links here” is a great way to scan the surrounding people, places, and things that have articles linking to your main topic.

The list of linked articles is sometimes surprising; it’s worth checking out when you’d like to get a quick overview of a topic. At the very least, you’ll find a list of the people and places that figure into the story.

I encourage you to start looking at Wikipedia articles in languages that are appropriate for a topic but in a language you don’t read, write or speak. You can use Google Translate to convert any articles into a language you do read.

Want to try it out yourself? Look at the English-, Turkish- and German-languages Wikipedia entries for Göbekli Tepe, a prehistoric site from around 9100 BCE that was found in central Turkey. As you read them, notice: In what ways are the articles in each language different? What could these differences tell you about the cultural perspectives of each?

Happy searching.

Excerpted from the new book The Joy of Search: A Google Insider’s Guide to Going Beyond the Basics by Daniel M. Russell. Copyright © 2019 Daniel M. Russell. Reprinted with the permission of The MIT Press.

Watch his TEDxPaloAltoHighSchool talk: