This tiny republic has the most startups per person and the fastest broadband speeds, and it offers something no other country does: e-residency. Estonia is aiming to create the ideal information society. Technology thinker and entrepreneur Andrew Keen goes there to find out how it works.

The future sometimes appears in the unlikeliest of places. The tiny country on the northeastern edge of Europe known as Estonia — or “E-stonia” as former president Toomas Hendrik Ilves calls it — has the most startups per person, the zippiest broadband speeds, and the most advanced e-government in the world.

Estonia has had the ill fortune to share a border with Russia and a sea with Denmark, Sweden and Germany, regional powers that have all been rather too related to the little Baltic republic. And yet this land of just 28,000 square miles is today — with South Korea, Israel, Singapore and its Scandinavian neighbors — one of the most wired and innovative countries. The government and people of Estonia are trying to invent the ideal information society and figuring out how to live well in cyberspace.

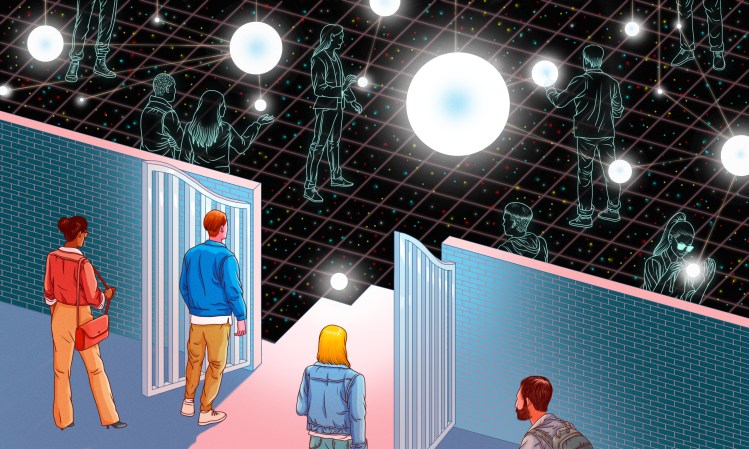

Estonia is the first country in the world to offer “e-residency”: an electronic passport that offers any businessperson the right to use legitimate Estonian legal or accounting online services and digital technologies. With this initiative, the country is disrupting the age-old intimacy between physical territory and citizenship. The e-residency program underwrites online identity by establishing fingerprints, biometrics and a private key on a chip.

“We want to be the Switzerland of the digital world,” says the director of the e-residency program in Estonia.

The goal is to have 10 million e-resident citizens by 2025, almost eight times the number of Estonia’s population of 1.3 million, according to the program’s director, Kaspar Korjus. He wants to create what he calls a “trust economy” for businesspeople around the globe — and a well-lit antithesis to the Dark Web, the digital hell infested with drug and arms dealers, pedophiles and criminals. “We want to be the Switzerland of the digital world,” Korjus says. Estonian Chief Technology Officer Taavi Kotka is more ambitious — we are becoming “the Matrix,” he tells me without smiling.

Given its inconvenient geography, Estonia has always struggled to find physical residents. E-residency creates a platform for a new kind of citizenship, Kotkus says. Not only is Estonia running a government in the cloud, it is also trying to create a country in the cloud: a 21st-century distributed community of people united by networked services rather than by geography.

Practically everything and everyone in Estonia is connected to the Internet: As measured in 2017, 91.4 percent of its citizens are Internet users; 87.9 percent of households have computers; 86.7 percent of Estonians have access to broadband; and 88.4 percent use it regularly. In neighboring Latvia, by contrast, 76 percent of its citizens are Internet users, while in Russia, Estonia’s former colonial ruler, that number is just 71 percent.

The country is planning a national test for digital competency in five areas, including the correct use of netiquette.

The education system has played an important role in this phenomenon. By the late 1990s, a government-backed investment fund was paying for Internet access for all schools, and teaching computer programming skills to kids as young as seven. “It’s like literacy,” one software engineer told me, describing how these skills are viewed in schools. The Estonian educational system has been redesigned to make people more responsible citizens. Schools have obligatory programs in “digital competence.” The country is even planning a national test for digital competency in five areas, including the correct use of netiquette. Education is “two steps ahead of the labor market,” says Kristel Rillo, who runs e-services at the Ministry of Education; he says that kids are turning out to be “two steps ahead of middle-aged workers in learning how to become digital citizens.”

But the most intriguing step in Estonia’s digital development is taking place outside the classroom. The key to its revolution is an identity card system that puts digital identity and trust at the heart of a new social contract. The mandatory electronic ID card, used by more than 95 percent of Estonians, gives everyone a secure online identity and offers a platform for digital citizenship featuring more than 4,000 online services, including voting, paying taxes and online storage of health and police records.

This online ID system is an attempt to “redefine the nature of the country” by getting rid of bureaucracy and reinventing government as a service. So says Andres Kütt, the chief architect of the Estonian Information System Authority. Kütt, a recent MIT graduate and former Skype employee, aims to integrate everyone’s data into a single, easy-to-navigate portal. Estonia wants to smash bureaucratic silos and distribute power down to the citizens so that government comes to them rather than their having to go to the government.

“The old model is broken,” Kütt says. “We are changing the concept of citizenship. This technology creates trust. It’s transparent. All agencies can access this data, but citizens have the right to know if their data has been accessed. In the old world, citizens were dependent on government; in Estonia, we are trying to make government dependent on citizens.”

In Estonia, citizens are empowered to watch the operations of government, and although the government can look at their data, it must notify them when it does so.

The ID system is supposed to be the reverse of Orwell’s Big Brother. In Estonia, citizens are empowered to watch the operations of government, and although the government can look at their data, it must notify them when it does so. Kütt gives me an anecdote of how the system works. He’d driven to a lecture in Tallinn to demonstrate the ID system. When he looked at his data, he saw that a police officer had accessed his information 30 minutes earlier. Following up in his online records, he found that an unmarked police car had followed his car because his license plate was dirty. The police accessed his records, checked his driver’s license, and decided not to stop him. The point of this story, according to Kütt, is to stress the accountability of government in this system. Nothing can be done secretly — the transparency is designed to protect individual rights and compound the trust between citizens and their government.

The most important aspect of the ID system is the creation of trust. Everyone I spoke to in Estonia, from startup entrepreneurs to policy makers to technologists to government ministers, agreed with Kütt on this point. Estonian trust in government is, in fact, much higher than the EU average. A 2014 study found that 51 percent of Estonians trust their government, in contrast with the EU average of 29 percent.

There are extremely significant potential consequences of the Estonian government’s entry into the data business. One result might be a new rivalry between sovereign governments and Silicon Valley’s private superpowers. “Governments are realizing that they’re losing the digital identities of their citizens to American companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple. And they are waking up to the realization that they have a responsibility to protect the privacy of these citizens,” says Linnar Viik, another architect of the ID card and a serial tech entrepreneur dubbed by the press “Estonia’s Mr. Internet.”

Personal data is what’s made these private superpowers so wealthy and powerful. Although the ID system doesn’t stop Estonians from using Facebook or Google, the database is designed as a rival ecosystem, a secure public alternative designed to benefit citizens rather than corporations. One of today’s great challenges is to reinvent the relevance of government in the new digital world, and that’s where the longer-term significance of the ID system may lie, according to Viik. “The government’s role is to protect the privacy of its citizens,” he says. “It’s an extension of public infrastructure, the 21st-century version of the welfare state.”

To some readers, particularly those who cherish their privacy, this ID system and its radical transparency might sound dystopian. But one of the unavoidable consequences of the digital revolution is the massive explosion of personal data on the network. Like it or not, this data is only going to grow exponentially with smart homes, smart cars, smart cities and all the other smart objects driving the Internet of things. We don’t have a choice about any of this. But we do have a choice about the amount of transparency we demand of the governments or corporations that have access to our personal data.

The country’s revolution remains a work in progress, and many ordinary Estonians remain indifferent to a lot of these digital abstractions.

Does this country without borders offer a preview of our 21st-century fate? Stuff may happen there first. Will it happen everywhere else next? Perhaps. The Estonian model comes with three important caveats.

First, it’s important to remember the country’s ahistorical exceptionalism. Like other startup nations such as Israel, Estonia has reinvented itself because of its good fortune in being able to stand outside history. Just as Israel began in 1948 without any legacy institutions or traditions, so the post-1991 Estonian digital revolution occurred because a new generation of technologically literate policy makers and politicians filled the vacuum created by the retreating Soviet bureaucracy.

Second, there is the distinctively unexceptional nature of the Estonian economy. Estonia is a relatively underdeveloped place, especially in comparison with postindustrial economies like the United States or Germany. A tech megabillionaire could buy Estonia outright if he wanted. Its per-capita GDP of around $17,600 is ranked 42nd in the world (above middle-rank economies like Russia and Turkey but a third of Singapore’s $52,900), and the average monthly wage, after taxes, of its workforce of 675,000 is under 1,000 euros. Reports of Estonia as the next Silicon Valley are, to be polite, slightly exaggerated.

The third caveat is separating its appearance from its reality. All the policy makers and legislators with whom I spoke have, in the best Silicon Valley fashion, drunk the Kool-Aid and loudly proclaim the triumph of their “country in a cloud.” But the truth is less triumphant. The revolution remains a work in progress, and many ordinary Estonians remain indifferent to a lot of these digital abstractions.

Nonetheless, Estonia matters because the government is prioritizing what Ilves calls “data integrity.” This prim-sounding issue will surely come to dominate conversations about 21st-century politics. What the republic on the northwestern edge of Russia can do is offer an alternate model of a transparent, open and fair political system, one that is the antithesis of the monstrous purveyor of untruth that’s emerging on its eastern border. One that prioritizes trust and is built upon the integrity of data. One, above all, that makes all of us accountable for our online behavior.

Excerpted from the new book How to Fix the Future by Andrew Keen. Published by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2018 by Andrew Keen.

Watch Andrew Keen’s talks from TEDxBerlin and TEDxDanubia: