Ranging in age from 17 to 25, they are challenging their country’s gender norms by learning engineering and coding, and setting their sights on infinity and beyond.

In Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, a dedicated group at the Kyrgyz Space Program is intently focused on building their nation’s first-ever satellite and prepping it for a 2019 mission. The surprise: the team consists of roughly a dozen young women between the ages of 17 and 25 — and Kyrgyz Space Program is the name they’ve given themselves.

Kyrgyzstan is a sparsely populated country in the mountains of Central Asia whose economy is based on agriculture and mining; more than 30 percent of people here live below the poverty line. And it’s not one of the 72 countries with an official space agency.

And yet, in March 2018, journalist Bektour Iskender (a TED Fellow) colaunched a free course to teach girls and young women how to build a satellite. “Women in our country are physically and spiritually strong. All we need is to believe in ourselves and get external support,” says Kyzzhibek, a 23-year-old on the team. “The mission of this program is not just about learning how to make and launch a satellite. It’s just as important to be a role model for girls afraid to explore and discover their talents.”

So … why did a news reporter start a space program? The story starts back in 2007, when Iskender cofounded a project he called Kloop. An independent, Bishkek-based journalism school, Kloop gives young people ages 14 to 25 the tools and chops to produce high-quality reporting, with an emphasis on politics, human rights, culture, music and sports. It encourages peer-to-peer learning by enlisting older students to teach the younger ones. And it changed education and journalism in Kyrgyzstan forever.

Kloop’s stories took aim at corrupt politicians, exposing serious abuses such as election-related bribes and fraud. Soon, the upstart reporters began scooping traditional press outlets. Today Kloop is recognized as one of the top five news sources within the country, surpassing even BBC Kyrgyz Service.

Then, in 2016, Iskender began thinking about a new frontier for Kloop: space. He met Alex MacDonald, another TED Fellow and a program executive for NASA’s Emerging Space initiative, which encourages and enables nascent space programs around the world. MacDonald told him about small, relatively inexpensive satellites that people who aren’t aerospace engineers can build and use. “I’ve been a fan of space exploration since I was a kid, so when Alex told me that you could build a launchable satellite for $150,000, I joked, ‘I’d love to send one to space!’” recalls Iskender. “But Alex started to convince me that Kloop should start its own program.”

It seemed like a stretch: what was the connection between a youth-led media company and space technology? The answer: computer programming. Coding courses were already part of the Kloop curriculum. “We work with open government data in our investigations, extracting data related to corrupt officials, and so on. For that, you need coders, which are expensive. So we decided to grow our own,” says Iskender.

Their data journalism courses were successful, so Kloop decided to add robotics instruction, to teach student journalists to operate drones for aerial reporting. That was when Iskender noticed a huge gender gap. “Despite an open call for the course, of the 50 people who showed up for it, only two were female,” he says. “It was reflective of a problem in Kyrgyz society: girls are brought up with an attitude that technology is not for them.”

This gender imbalance was a problem. “Kloop is known in our country as the most feminist-friendly, LGBT-friendly media outlet — maybe in the whole of Central Asia,” he says. “We have the largest number of female camera operators, for example, and our sports editor is an 18-year-old girl. We also have a brilliant video engineer who is also a young woman.”

In response, Iskender and Kloop cofounder Rinat Tuhvatshin considered setting up a girls-only robotics course in 2017. Then, they thought, Why not integrate satellite building into the course? Iskender says, “A satellite-building school for girls only — what a strong message it would be for our patriarchal society, to have Kyrgyzstan’s first satellite built by a group of young women!”

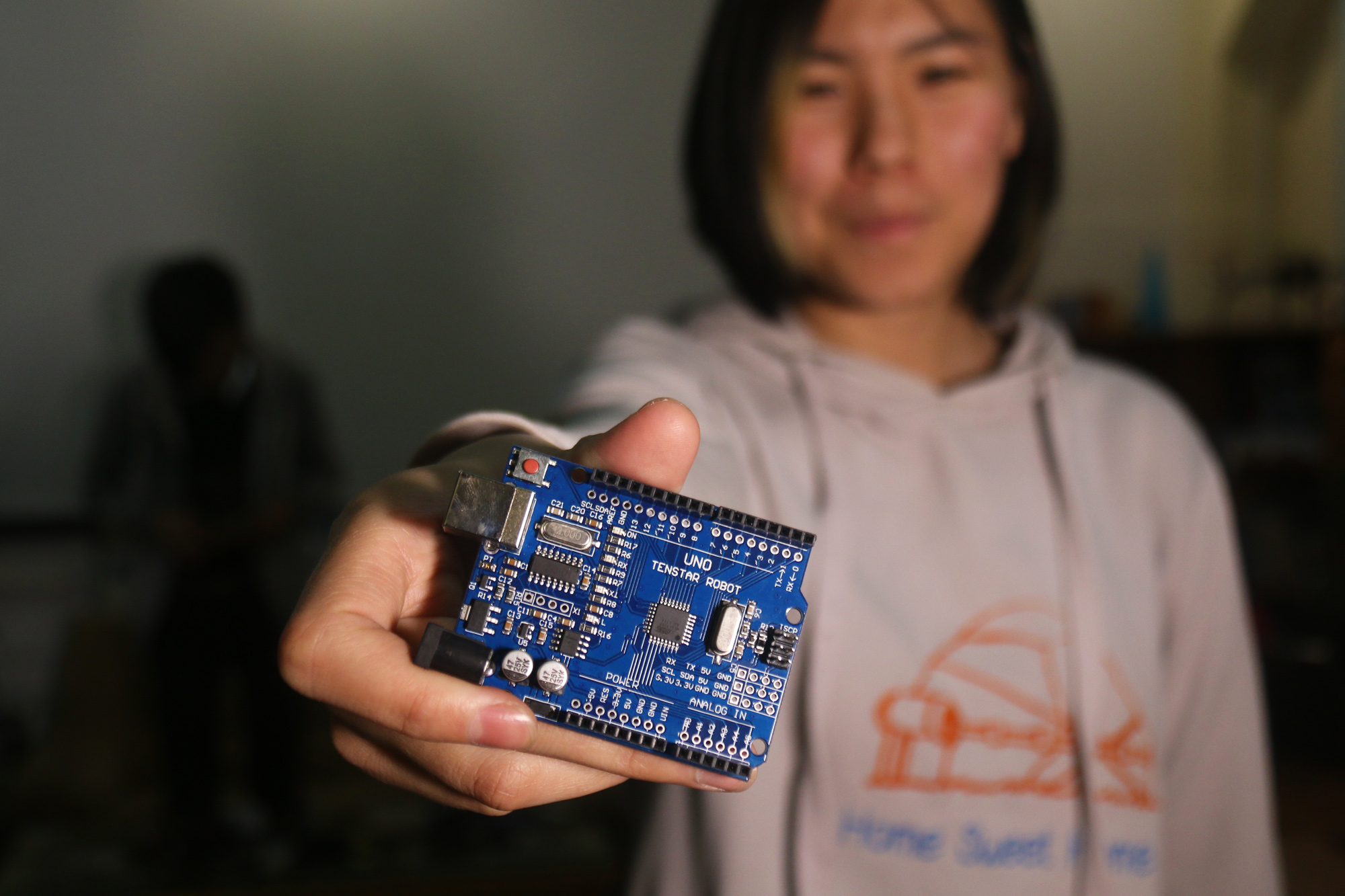

Kloop put out a call for women and girls with some coding experience to join the class. About 50 young women turned up, and now, a dedicated group of a dozen meet twice a week at Kloop’s office, where they’re led by two alumni of Kloop’s programming course. They’ve spent the first part of the class learning engineering basics, including how to solder and work with Arduino hardware. They’re also receiving instruction in coding (if they’re not already proficient) and 3D printing.

What are they building? A CubeSat. CubeSats are microsatellites typically used to conduct scientific research in low Earth orbit. Each cube is 10x10x10 cm, and can be customized to take all sorts of different measurements, shoot photos or even host a tiny science experiment. CubeSats are cheap to build, and they’re cheap to put into orbit too; because they’re so small, they can squeeze into the payload of someone else’s spacecraft. “We don’t have to build a rocket, fortunately,” says Iskender. “That would be too expensive and complicated for us at this stage.”

For their first satellite, the team has pretty humble goals; they want to launch a working device that is able to send and receive signals. However, they’ve recently gotten funding — the program is supported by Patreon donations, and Kloop is also seeking private grants — for a second satellite, which will be more complicated. The group is looking into several experiments, including one that would prove whether it’s feasible to use space junk as rocket fuel. “They’re exploring the idea of directing the sun’s rays toward orbiting garbage to vaporize it and use the energy to propel the CubeSat,” says Iskender. “They’re also considering using it to take satellite imagery of the Tibetan plateau, one of the least photographed places in the world from space.”

“We’d like to involve girls in more areas mainly occupied by boys, not only space exploration,” Iskender says. But he worries that Kloop’s gender-busting efforts may have limited impact in Kyrgystan, a nation where young women are still kidnapped and wed against their will. “How do we change this?” he asks. “You can publish stories, and we do, but that’s not enough. Having Kyrgyzstan’s first space program be launched by young women — it destroys all the norms beautifully.”

Just ask Kyrgyz Space Program member 21-year-old Aiganysh. “At first I thought this idea was crazy; now I clearly see that it’s brilliant,” she says. “This experience has definitely changed my mindset. It’s made me believe that with passion, anything is possible.”

All images courtesy of Kloop.

If you’d like to support the Kyrgyz Space Program, visit its Patreon page.

Watch Bektour Iskender’s TED talk here: