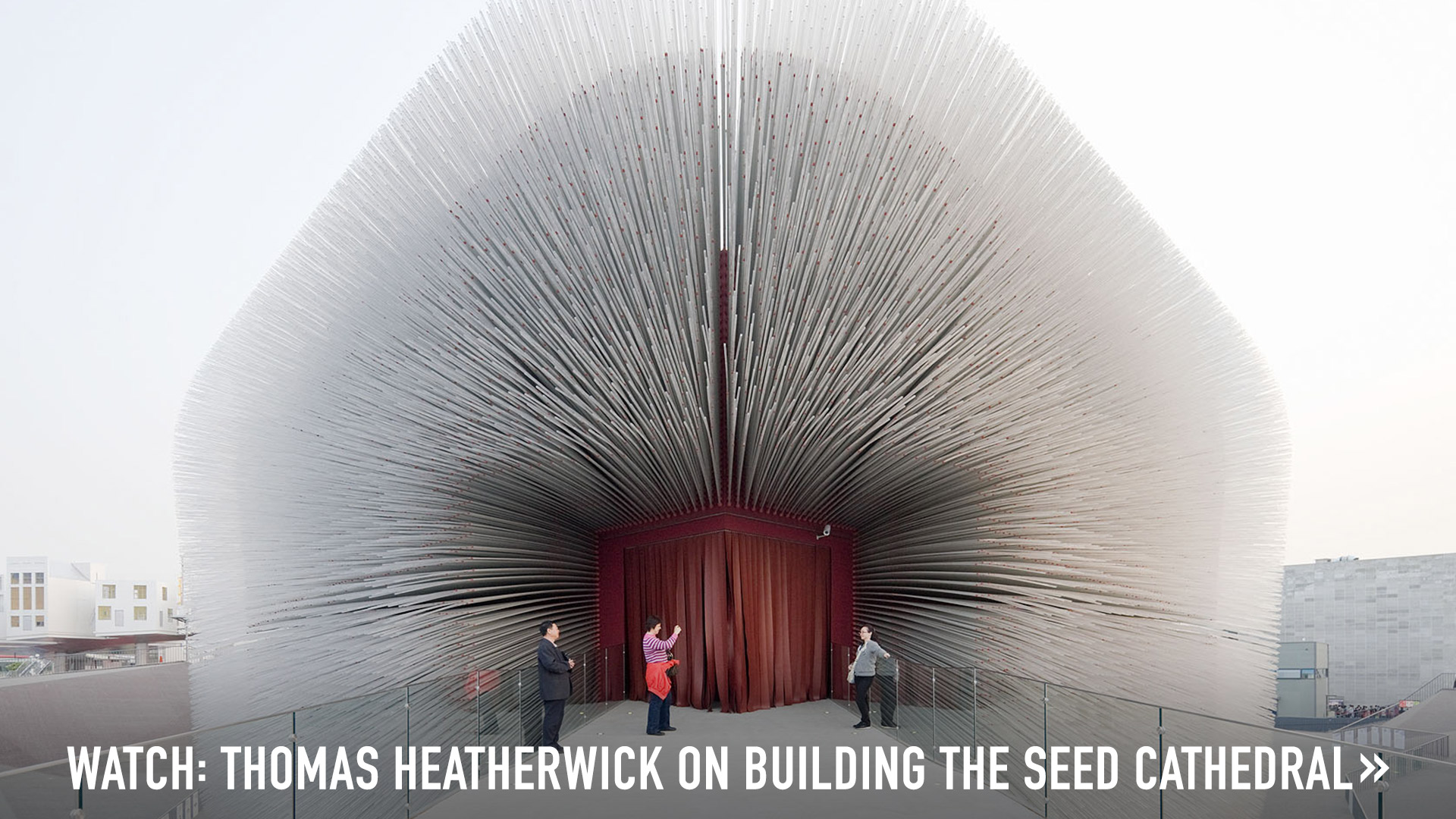

“I am in love with cities,” says British designer and architect Thomas Heatherwick (TED Talk: Building the seed cathedral). “It’s just incredible that we all live together, and together we add up to something incredibly rich.” Heatherwick has already come up with some pretty bold urban designs — including a garden-topped bridge across the River Thames, and London’s sleek new red city buses, wrapped in ribbons of glass. Here, the soft-spoken, 45-year-old architect describes how to bring a human scale and whimsical sensibility to urban life, to create a fabulous future fit for us all.

Every city has a unique chemistry. “We have a duty to protect the idiosyncrasies we discover in each city, and not treat them like luxuries,” Heatherwick says. Preserving that richness is a foundational philosophy for his London studio, founded in 1994 and now with a staff of 160 and design projects in metropolitan areas all around the world. “Otherwise we risk forgetting the unique local factors that make a place special. Sadly, these are vanishing, making the equator and the Arctic Circle all look the same.” For Pier55 in Manhattan, a public park and performance space, Heatherwick has come up with an undulating topography of lush lawns and pathways on a structure that juts into the Hudson River, with sweeping city and water views that celebrate the city’s dynamic skyline and its relationship with the sea.

The best signature style is no signature style. Some architects have a distinct style that can be spotted a mile away: the biomorphic forms of Zaha Hadid, for instance, or Frank Gehry’s sculptural sheets of metal on roofs and facades. Heatherwick says his main interest is making things different. “It feels rude to go around the world imprinting your [design] DNA everywhere,” he says. “Every project needs its own philosophy, and that will lead the outcome.” So a set of artist studios in Wales are clad in hand-crinkled, paper-thin steel, while his design for the Bombay Sapphire gin distillery in Laverstoke, England, has arched glasshouses connected to historic brick mill buildings.

Design is physical work. Often involving axes. Designers are makers and tinkerers, and in the Heatherwick Studio you’ll find axes, chisels, chainsaws and other hand tools and see staff mixing concrete and experimenting with materials like copper, bronze and paper. (The “Spun” chair, for instance, is made from rotation-molded plastic.) They also use computers and 3D printers, of course, but Heatherwick warns against depending on technology for too much creative firepower. “If something is complex, we give up and think computers can do it all, but computers can’t think. In fact, they handicap some parts of the thinking process,” he says. “Let’s keep a balance between hammers and 3D printers. After all, how many objects do you really love that have been 3D printed?”

The greatest project of all is day-to-day life. “We realized in a moment of navel-gazing that the biggest project we’ve had is the studio itself and how our work and approach has evolved over 20 years,” Heatherwick says. “We’re not experts at anything, but we’re experts at not being experts, and we’ve developed a system to do this.” That means thinking large and then zooming in close, doing research and analysis, hunting down the real problem to solve, and asking questions and breaking that down “until the real thing is discovered.” At the studio, designers test and experiment with materials to see how people respond to its touch and feel. “There is a great responsibility, because some of the things we create are among the biggest objects made by we wee humans,” he says.

America is a land of opportunity. After establishing his reputation in the UK and taking on projects in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, the US now looms large for Heatherwick. High-profile assignments on the drawing board include the new Google headquarters in Mountain View, California (with Danish architecture firm BIG), and a multimillion-dollar public space and artistic centerpiece for the Hudson Yards development on the west side of New York City. “There is a sense of possibility in the US, and a phenomenal energy,” he says. That’s especially true of New York, a city he’s been visiting for more than 40 years. “The passion and enthusiasm ran out in the 1970s and ’80s, but in the last ten years the confidence has come back. The wind is in the sails again, and that is a great relief.”

Provocations: The Architecture and Design of Heatherwick Studio is on show at the Cooper Hewitt in New York City until January 3, 2016. Image of the proposed Garden Bridge in London courtesy of Arup.