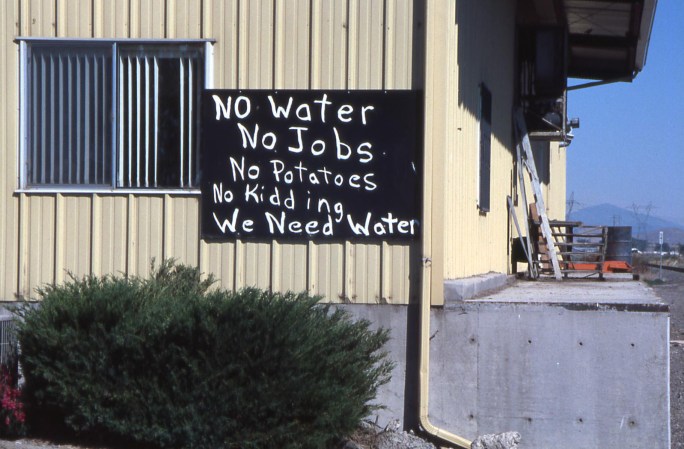

Most disasters come with heart-breaking visuals — innocent victims, burned wreckage. Our looming water disaster is invisible. Will anyone notice before it’s too late?

Last week in Fresno, California, in the middle of areas hardest hit by the state’s five-year drought, Donald Trump voiced the opinion that “there is no drought.” Instead, he blamed the whole problem on the state’s water management policies; columnists, writers and politicians denounced him (again) as a morally bankrupt fabulist.

But just as he so often plays to our hopes and fears, Trump had aimed his rhetoric right at our Achilles’ heel — the enormous human capacity for denial. If there’s one thing that Americans love to deny, it’s how fast we are burning through the nation’s freshwater supply. Sure, we can worry about California and its dried-up lake and river beds. But the rest of the country? The rest of the world?

Cynthia Barnett first started looking into the relationship between humans and water around 15 years ago, when she was a journalist in Florida. The state was in the grip of an intense, multi-year drought, groundwater levels reached new lows, hundreds of sinkholes opened up and wildfires raged. What was going on? As Barnett started investigating, she soon realized the state’s century-long spree of real estate development had drained wetlands and diminished the state’s freshwater access (including making massive incursions into the treasured Everglades).

She soon saw that water wasn’t — isn’t — only Florida’s problem; the global water crisis is growing ever more intense. Barnett, who went on to write various books exploring society’s relationship with water, explains why we need to develop a responsible and realistic water ethic of the world’s freshwater supply — and why that goal seems so elusive.

First, the problem. Shortages of freshwater aren’t the future — they are here now. Four billion people already face water shortages, with two thirds of the world’s population living under conditions of severe water scarcity for at least one month each year. Half a billion people face severe shortages all year round, as freshwater comes under increasing demand from growing populations, increased living standards and the expansion of irrigation. And while most of the people facing severe shortages live in countries such as India and China, the United States has a significant population — 130 million people — likely to be affected.

Then, the goal. Barnett’s wants the world — person by person, country by country — to adopt a water ethic. That means “living with water in a way today that doesn’t jeopardize the ability of future generations and ecosystems to live well with water, too.” She likens the necessary shift in attitude to the one that led to a sharp decline in littering since the 1970s. “Practically speaking, it means using less and polluting less,” she says. The idea has been around for years. It dates back to the early, 19th-century days of the conservation movement, and started picking up more followers in the 1930s, through the work of environmentalist and Wilderness Society founder Aldo Leopold. Then, it really picked up steam in the late 1960s and 1970s, when water pollution reached alarming new highs. In the 1990s, the movement became more international thanks to people like Sandra Postel, who founded the Global Water Policy Project. But the concept has not yet caught serious traction with the public. So, while a Youtube video on water scarcity produced by a United Nations entity has had almost 170,000 hits, that talking dog has had more than 170,000,000. The math doesn’t look good.

We settled one of the most water-rich continents in the world, and in only a few generations managed to make freshwater the single-most degraded of all our natural resources

Then, the problem with the goal. Unlike most other pressing social issues, water has a big problem: invisibility. Smog and pollution are highly conspicuous — the dwindling water supply isn’t. With more than 60 percent of the planet’s freshwater packed in the polar icecaps and 30-odd percent of it lying in the ground beneath our feet, it’s hard to get passionate about something you can’t really see. “I’m convinced that people would live differently if they knew what was happening to water,” says Barnett. She points out that in drought-plagued California, people have heeded the call to use less water and farmers have introduced measures to conserve water. (While figures still vary widely by region, per person water use had dropped to 67 gallons a day in April 2016, down from 123 gallons in September 2014.) But that’s California. Unless there’s an obvious crisis, people don’t or won’t see the problem, “You hear people voicing a lot of confidence in the groundwater they can’t see, even if their lake water is dropping,” she says. “They don’t understand that the two are connected.”

Water denial is real. The 20th century saw massive feats of engineering send oceans of water flowing to American homes and lawns — and it has created a false illusion of abundance. “That great achievement has grown into entitlement,” says Barnett. Perhaps the best emblem of that entitlement and denial? America’s beloved tapestry of landscaping, the verdant sward of green surrounding so many houses. “The lawn is America’s largest crop,” Barnett wrote in her 2011 book Blue Revolution, describing the country’s more than 60,000 square miles of endlessly irrigated, emerald lawns as the nation’s 51st state — area-wise, it’s right between Wisconsin and Georgia. And all that grass needs a lot of water.

“We settled one of the most water-rich continents in the world, and in only a few generations managed to make freshwater the single-most degraded of all our natural resources,” Barnett says. “I think it’s fair to say that, for the first time since the environmental protections of the 1970s, children growing up in America today are not inheriting waters as clean and abundant as when they were born.”

Goal One: End denial on a personal level. Changing people’s minds about water starts with changing their minds about the weather. “Climate change frightens and divides us to such an extent that many people simply refuse to talk about it at all,” Barnett wrote in her book Rain. Instead, she thinks, we should talk about the weather. “People love to talk about the rain,” she says. “Rain is a conversation we all take part in.” She hopes that if we learn to appreciate wet weather, that interest can extend to efforts to conserve, reuse and recycle rainwater. Los Angeles, for example, was built to withstand floods, and historically had planned and built infrastructure to push rain and floodwater out to sea. Today, the city is beginning to remake its relationship with rain, to give floodwater a place to go and reuse it over and over again. Efforts to keep water local in wetlands and aquifers are key if future generations are going to have water.

Goal Two: End denial on an industrial level. While awareness of water will start with people, says Barnett, government and business have no incentive to change unless people speak up. To be successful, any water ethic has to be embraced by industry, since agriculture and energy draw the largest share of the country’s water resources. “The ethic has to be a new way of living with and valuing water in every sector of the economy,” Barnett said at a recent conference.

History shows that change is possible. In 1969, pollution-fueled flames erupting on stretches of Ohio’s Cuyahoga River sparked public outrage, spurring the passage of the Clean Water Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and finally putting industries on the hook for reckless, toxic dumping. A new groundswell of support for a new freshwater ethic will have to come from the people, too — but the outrage will have to come without a river on fire.