How can humans survive if the world gets drier? Here’s one scientist’s answer … so-called “resurrection” crops.

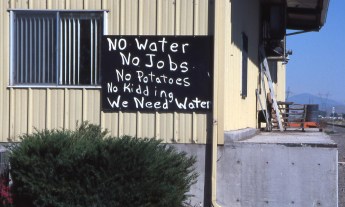

Ever since humanity began to farm our own food, we’ve faced an unpredictable frenemy: rain. It comes and goes without much warning, and a field of lush leafy greens one year can crackle, dry up and blow away the next. Food security and fortunes depend on rain, and nowhere more so than in Africa, where 96% of farmland depends on rain instead of the irrigation common in more-developed places. It has consequences: South Africa’s ongoing drought — the worst in three decades — will cost it at least a quarter of its corn crop this year.

Biologist Jill Farrant (TED Talk: How we can make crops survive without water) of the University of Cape Town in South Africa says that nature has plenty of answers for people who want to grow crops in places with unpredictable rainfall. She is hard at work finding a way to take traits from rare wild plants that adapt to extreme desiccation and use them in food crops. As the Earth’s climate changes and rainfall becomes even less predictable in some places, those answers will grow even more valuable. “The type of farming I’m aiming for is literally so that people can survive as it’s going to get more and more dry,” Farrant says.

Extreme conditions produce extremely tough plants. In the rusty red deserts of South Africa, steep-sided rocky mounds called inselbergs rear up from the plains like the bones of the earth. The hills are remnants of an earlier geological era, scraped bare of most soil and exposed to the elements. Yet on these and similar formations in deserts around the world, a few ferocious plants have adapted to endure under ever-changing conditions.

Farrant calls them resurrection plants. During months without water under a harsh sun, they shrivel and contract until they look like a pile of dead gray foliage. But rainfall can revive them in a matter of hours. Her time-lapse videos of the revivals look like someone playing a tape of the plant’s demise in reverse.

The big difference between “drought-tolerant” flora and these tough plants: metabolism. Many different kinds of plants have developed tactics to weather dry spells. Some plants store reserves of water to see them through a drought; others send roots deep down to subsurface water supplies. But once these plants use up their stored reserve or tap out the underground supply, they cease growing and start to die. They may be able to handle a drought of some length, and many people use the term “drought tolerant” to describe such plants, but they never actually stop needing to consume water, so Farrant prefers to call them drought resistant.

Resurrection plants, defined as those capable of recovering from holding less than 0.1 grams of water per gram of dry mass, are different. They lack water-storing structures, and their niche on rock faces prevents them from tapping groundwater, so they have instead developed the ability to change their metabolism. When they detect an extended dry period, they divert their metabolisms, producing sugars and certain stress-associated proteins and other materials in their tissues. As the plant dries, these resources take on first the properties of a honey, then rubber, and finally enter a glass-like state that is “the most stable state that the plant can maintain,” Farrant says. That slows the plant’s metabolism and protects its desiccated tissues. The plants also change shape, shriveling to minimize the surface area through which their remaining water might evaporate. They can recover from months and years without water, depending on the species.

What else can do this dry-out-and-revive trick? Seeds — almost all of them. At the start of her career, Farrant studied “recalcitrant seeds,” such as avocados, coffee and lychee. While tasty, such seeds are delicate — they cannot germinate if they dry out (as you may know if you’ve ever tried to grow a tree from an avocado pit). In the seed world, that makes them rare, because most seeds from flowering plant are quite robust. Most seeds can wait out the dry, unwelcoming seasons until conditions are right and they begin growing. Yet once they start growing, such plants seem not to retain the ability to hit the pause button on metabolism in their stems or leaves. After completing her Ph.D. on seeds, Farrant began investigating whether it might be possible to isolate the properties that make most seeds so resilient and transfer them to other plant tissues. What Farrant and others have found over the past two decades is that there are many genes involved in resurrection plants’ response to desiccation. Many of them are the same that regulate how seeds become desiccation tolerant while still attached their parent plant. Now they are trying to figure out what molecular signaling processes activate those seed-building genes in resurrection plants — and how to replicate them in crops. “Most genes are regulated by a master set of genes,” Farrant says. “We’re looking at gene promoters and what would be their master switch.”

Now, to add those resilient genes to useful crops. Once Farrant and her colleagues feel they have a better sense of which switches to throw, they will have to find the best way to do so in useful crops. “I’m trying three methods of breeding,” Farrant says: conventional, genetic modification and gene editing. She says she is aware that plenty of people do not want to eat genetically modified crops, but she is pushing ahead with every available tool until one works. Farmers and consumers alike can choose whether or not to use whichever version prevails: “I’m giving people an option.” Farrant and others in the resurrection business got together last year to discuss the best species of resurrection plant to use as a lab model. Just like medical researchers use rats to test ideas for human medical treatments, botanists use plants that are relatively easy to grow in a lab or greenhouse setting to test their ideas for related species. Boea hygrometrica, also known as the Queensland rock violet, is one of the best studied resurrection plants so far, with a draft genome published last year by a Chinese team. Also last year, Farrant and colleagues published a detailed molecular study of another candidate, Xerophyta viscosa, a tough-as-nails South African plant with lily-like flowers, and she says that a genome is on the way. One or both of these models will help desiccation researchers test their ideas — so far mostly done in the lab — on test plots.

Understanding the basic science first is key. There are good reasons why crop plants do not use desiccation defenses already. For instance, there’s a high energy cost in switching from a regular metabolism to an almost-no-water metabolism. It will also be necessary to understand what sort of yield farmers might expect and to establish the plant’s safety. “The yield is never going to be high,” Farrant says, so these plants will be targeted not at Iowa farmers trying to squeeze more cash out of already-lush fields, but subsistence farmers who need help to survive a drought like the present one in South Africa. “My vision is for the subsistence farmer,” Farrant says. “I’m targeting crops that are of African value.”