This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from people in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

Racism does not occur exclusively in flashpoint moments of violence; it is also like a poisonous mist that slowly kills us. This reality of interpersonal racism is often described as “everyday racism” or “casual racism.” Yet these phrases may falsely imply that the severity and dangers of racism should be downplayed.

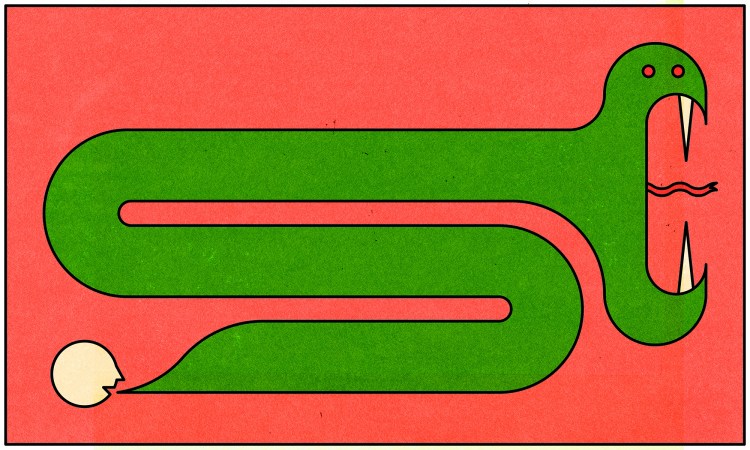

In 1970, Harvard psychiatrist Chester M. Pierce PhD coined the term “microaggression” to describe the dismissive, insulting and disrespectful treatment suffered by Black individuals at the hands of non-Black individuals, and this word is often misunderstood as minor or inconsequential racist actions. However, microaggressions are not small, nor should they be taken lightly. Microaggressions can be better understood as “death by a thousand cuts,” which can be detrimental to a person’s health, safety, opportunities, livelihood, personhood and more.

Microaggressions have become so ubiquitous that those who commit them might not consider them to be racist.

While overt acts of racism — such as physically harming someone due to racist beliefs — are what we most commonly associate with interpersonal racism, racism takes many forms. Microaggressions have become so ubiquitous that those who commit them might not consider them to be racist.

Below are examples of some common comments and questions that are rooted in racism, with explanations of why they should be avoided.

1. “I don’t even see you as [racialized identity].”

When we say something like this, not only does it ignore and minimize the identity of the other person, but it also indicates that in systems of white supremacy, we can only humanize individuals when we separate them from their racialized identity. Sharing our perceptions about someone’s racial or ethnic group is never complimentary – it’s actually insulting and racist. It’s crucial to work on why we might view someone as an “exception” to our racist assumptions instead of evaluating how the assumptions we may hold are racist.

2. “You must be good at [insert activity stereotypically associated with a racial or ethnic group].”

The fallacy that race has a biological basis has resulted in the untrue notion that certain racialized groups have particular skills or proclivities for particular activities. The best way to figure out someone’s interests and talents is to get to know them personally, not to make assumptions based on their racialized identity.

3. “You are so articulate/well spoken.”

When we act surprised that an individual exceeded our racist assumptions about them, it says more about us than it does about that person’s capacity. These harmful statements reveal the racist perception that racialized people are at an “intellectual or cognitive disadvantage” to white people. In general, we should compliment people on the substance of their work, not their ability to communicate that work. However, this praise may be appropriate in the case of oratory or speech-related actions.

No one is entitled to know the details of someone’s racialized identity or ethnic heritage.

4. “Do you know [other racialized person]?” or “You look just like [other racialized person].”

A major aspect of dehumanization is the failure to recognize that people are individuals and are not connected to every member of their racialized group. Assuming that all members of a racialized group know each other or look alike is racist. When commenting on who looks like or may know whom, we should be mindful whether we are making a genuine observation based on what we know to be possible or whether we’re making racialized assumptions.

5. “What are you?”

This question is often heard by people whose external appearance cannot be easily categorized based on popular understandings of racial groups (and, unfortunately, “a human being” never seems to be a satisfactory answer). The question stems from the impulse to easily and quickly categorize a person by racial group and strips someone’s personhood away from them (the goal of racism). No one is entitled to know the details of someone’s racialized identity or ethnic heritage.

6. “Where are you really from?”

Usually asked as a disbelieving follow-up to “Where are you from?”, this question typically does not come from genuine interest in someone’s national or cultural origin. It actually comes from the racist inclination to racialize and categorize people according to race.

If someone tells you where they are from, believe them. Unless our job is to check passports or work on the census, we don’t need to know where someone is from. Even if this line of questioning is not meant to be offensive, it is a common microaggression that racialized people experience. It’s important to learn about people in intentional and authentic ways, accept the personal information they choose to share without interrogating them, and check our biases along the way.

In getting smarter about interpersonal racism, it’s common to reflect on what we may have gotten wrong in the past and to want to reach out to people whom we have said harmful things to and make amends. Since racism creates power dynamics, it’s likely that the harmed person didn’t speak up about it because they weren’t in a position of power to do so or because our actions violated the basic tenets of a relationship based on mutual respect. This is one reason why it can be uncomfortable to get smarter about racism — we gain greater context and understanding about how we have failed in the past.

It is not the responsibility of the people we have harmed to make us feel better or alleviate our guilt.

While it can be upsetting to know we’ve done something harmful, acknowledging harm is not nearly as upsetting as experiencing harm. Learning is a blessing, not a burden, and learning about the ways in which we can stop ourselves from being harmful is a privilege. If you have hurt someone — as many of us have at some point or another — the best way to demonstrate improvement is to do better. But we must take responsibility for our own improvement, not make it the responsibility of others.

If you realize while reading this that you may have done something that was problematic or hurtful to another person, stifle the impulse to immediately reach out. Instead, first examine what led you to take that action in the first place and how you can work to prevent similar action in the future. Also consider whether it would cause more harm or distress to reach out or if the best course of action is for you to simply do better in the future.

It is not the responsibility of the people we have harmed to make us feel better or alleviate our guilt. We must take care not to center our own feelings rather than recognize the work we must do going forward. Sit with the discomfort that you have done something racist, and let it motivate you to avoid such behavior in the future.

Reprinted with permission from the book Read This To Get Smarter about Race, Class, Gender, Disability, and More by Blair Imani copyright © 2021. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Watch her TEDxBoulder Talk here: