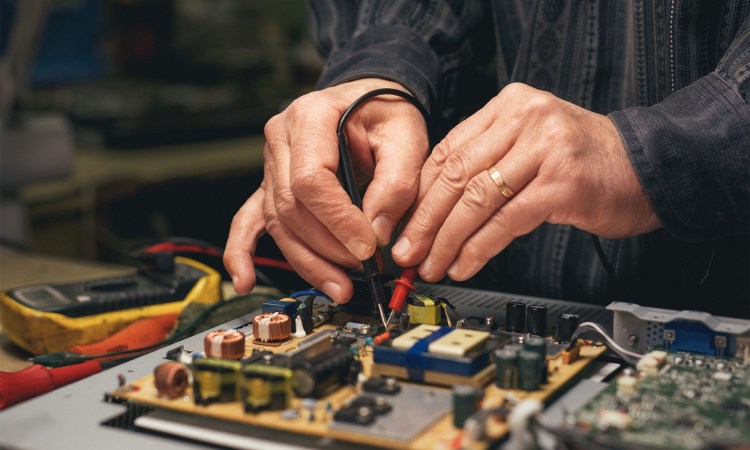

Roman Hottgenroth is surrounded by lamps, dishwashers and vacuum cleaners. Computers, smartphones and TV receivers are piled high on tin shelves behind him. A group of washing machines rattles loudly in test mode, only somewhat drowned out by the bass thumping from a hi-fi system an employee is checking.

None of these products work properly, and that’s the point.

Here at Stilbruch, the department store in Hamburg, Germany run by the city’s sanitation department, only goods that others have thrown away are offered up for sale. But before they are sold, they are checked and, if necessary, repaired in Hottgenroth’s 7,500-square-foot workshop. The process is something of a dying art. “Unfortunately, [repair] is no longer intended for most appliances,” says Hottgenroth, Stilbruch’s operations manager.

But that may be changing. Across Europe, legislation is pushing back against a waste-based economy and restoring something that companies have gradually taken away from citizens: The right to repair what they’ve bought.

At over 10 million tons per year, e-waste is the fastest growing waste stream in Europe.

Hottgenroth sees every day how many appliances end up in the trash. Although often all they need is a fresh battery or receiver, “spare parts are hard to come by, and all the components are soldered, glued or riveted,” he says. This is why, while his employees can fix many products, many others are unsalvageable. “Because of their design, devices often break just when you try to open them.” In addition, there is usually no longer any provision for upgrading and adapting devices to new technical standards.

“This should be banned,” Hottgenroth says flatly.

Some political leaders agree. In November, the EU Parliament called on the European Commission to make routine repair of everyday products easier, systematic and cost-efficient. It said that warranties should be extended, and that replacement parts should be improved and made more accessible, as should information enabling general repair and maintenance.

The EU’s existing eco-design regulations could be an instrument to reach these goals. These mandates were established years ago to improve the energy efficiency of products sold in the EU.

But in March, the first eco-design regulation that will define standards for repair and useful life will come into force. Manufacturers of washing machines, dishwashers, refrigerators and monitors will have to ensure that components are replaceable with common tools. Instruction manuals must be accessible to specialist companies. And producers must supply spare parts within 15 days.

Cell phones, computers and tablets, however, have not yet been regulated by an EU eco-design directive, and constitute some of the most harmful consumer waste. To this end, individual member states have moved ahead with their own regulations.

This month, France will introduce an anti-waste law with a repair index. A grade of 1 through 10 will appear on the labels of washing machines, laptops, smartphones, TVs and lawnmowers. This score will be calculated based on criteria such as ease of disassembly, access to repair information, and price and availability of spare parts. The French government is also promoting modular product design and is aiming to have 60 percent of electronic equipment in France be repairable by 2026.

Nearly 80 percent [of EU citizens] would rather repair their devices than replace them. And a majority think that manufacturers should be legally obliged to facilitate the repair of digital devices.

Europe is one of the largest markets in the world, which means that new EU design guidelines and right to repair mandates could force manufacturers across the world to make more durable products. The shift can’t come soon enough. At over 10 million tons per year, e-waste is the fastest growing waste stream in Europe. In Germany alone, two million tons are generated annually. Repairing products and extending their useful life could play a key role in mitigating the environmental consequences of all this waste.

And that’s exactly what a large majority of EU citizens want. Nearly 80 percent would rather repair their devices than replace them. And a majority think that manufacturers should be legally obliged to facilitate the repair of digital devices or the replacement of their individual parts.

Such products have existed for some time — companies like Fairphone and Shiftphone produce sustainable, repairable smartphones, for instance. But with the EU’s new legislative mandates on the horizon, bigger players are getting ahead of the game.

Apple has launched a repair program for independent businesses, in which companies can get Apple parts, tools, training, service guides, diagnostics and resources to perform a variety of out-of-warranty repairs. Last year the German outdoor gear company Vaude began providing customers with an index showing how repairable each of its products are. Electrolux, a leading manufacturer of electrical appliances in Europe, has been preparing for the directive and will be ready to comply once it takes effect in March.

“We will now ensure that the specific parts, according to the legislation, will be available directly to consumers,” says Viktor Sundberg, vice president of European & environmental affairs at Electrolux. “And we will make the repair information available to independent repairers for the categories requested.”

It’s a movement that has as much to do with altering mindsets as fixing gadgets.

Is that sufficient? For Dorothea Kessler of iFixit Europe, the EU Parliament has indeed sent a strong signal that the continent must embrace a more sustainable circular economy. But it’s only a start. “We will certainly have to wait a few more years for feasible measures to emerge for the most important product categories,” she says. In the process, she believes it won’t be easy for the EU to stand up to the manufacturers’ lobbies.

Consumer and environmental organizations have also welcomed the EU Parliament resolution with cautious optimism. “The right to repair was already in the Green Deal of December 2019 as a buzzword,” says Elke Salzmann of the Federation of Consumer Organizations in Germany, referring to Europe’s commitment to become the first climate-neutral continent. “But we have to take care that the promise will be obliging.”

In the meantime, iFixit has been assigning a repairability rating to every new device on the market for years and provides free step-by-step instructions for do-it-yourself repairs in 11 languages for 70,000 products. Its online forum allows users to exchange ideas with other tinkerers.

The online community, founded in California, now has three million monthly users in Europe and ten million worldwide. To Kessler, it’s a movement that has as much to do with altering mindsets as fixing gadgets. “Our philosophy is that something doesn’t belong to you if you can’t open it,” she says.

This story originally appeared in Reasons to Be Cheerful and is republished here as part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems.

When you toss a broken toy or old pair of socks into the trash, those things inevitably end up in ever-growing landfills. Sustainable materials expert Andrew Dent shares why we need to get smarter about the way we make — and remake — our products: