The US has a housing problem. Not only are there too few homes, those that we have are gluttons, using almost twice as much energy per home as those in Europe. Only Canada’s homes — most of which endure long and biting winters — use more.

America’s leaky, inefficient homes produce nearly one-fifth of the country’s energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, a number that has probably crept higher as the pandemic has kept people at home. That’s because most homes are stubbornly stuck in a previous generation. The median age of a US home is 37 years, and it’s not getting any younger. Many houses and apartments are still heated and powered by fossil fuels. If we’re going to meet the Paris Agreement goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent from 2005 levels by 2050 — as many states and municipalities are still striving to do — we have some work to do.

More than 40 percent of our energy use at home comes from electricity, and the absolute amount has risen seven-fold from six decades ago.

More than 40 percent of our energy use at home comes from electricity, and the absolute amount has risen seven-fold from six decades ago. Greenhouse gas emissions from household electricity use have dropped 31 percent since 2005. But the dip is largely the result of a decline in coal power plants, not changes in home energy use.

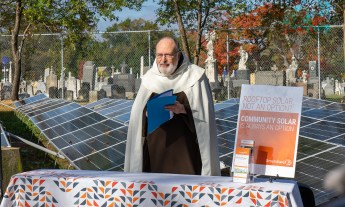

Fortunately, eliminating electricity-based emissions is relatively easy. Many homeowners can put up solar panels today and reap enough energy savings to cover the investment in about eight years — and sometimes less. For those who can’t, pushing utilities to phase out fossil fuel power plants in favor of solar, wind and other forms of renewable energy would be a boon. Eliminating carbon from the grid alone would slash nearly half of household emissions.

Unfortunately, taking care of the rest won’t be so easy. “Heating is still the largest portion of household energy use,” said Benjamin Goldstein, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan who was the lead author of a new study that looked at how US homes could eliminate fossil fuels. Across the country, millions of home furnaces still burn natural gas, oil and even coal. That’s one reason fossil fuels still account for 80 percent of the country’s energy use. To fully wean ourselves from carbon, we’ll have to tackle home heating, too.

In short, we need to rethink housing from the ground up, Goldstein says. “We need to have a bunch of actions, from individual to structural changes, in order to make the housing stock meet the carbon goals.” Because a new home built today will likely be around in 2050, we have no time to waste.

For new homes, there’s a relatively straightforward solution, and that’s simply to build them better. Several states have adopted stringent building codes when it comes to energy efficiency in new homes. In Massachusetts, most towns now require new homes to be at least 15 percent more energy efficient than those built to the current standard code, with incentives for builders to strive for even greater improvements. The construction costs are higher, but the state says that homeowners can expect to save money from day one in most cases.

Improving buildings’ energy efficiency will also go a long way toward alleviating energy poverty.

Still, there’s room to improve these codes. Travis Anderson, director of design at Placetailor, a Boston-based architecture and development cooperative, says the most underestimated factor in energy efficiency is airtightness — how well the home is sealed off from the outdoors. He came to that realization when tweaking models he developed for the city of Boston, which is looking to zero out carbon emissions in its housing portfolio by 2050. That discovery had surprising benefits. When Anderson improved a home’s sealing, he was able to use less insulation, install lower performance windows, and lower costs, while still meeting stringent energy targets. “You can’t make a building too airtight,” he said. “I think code is still lacking in that regard.”

Improving buildings’ energy efficiency will also go a long way toward alleviating energy poverty. Renters are at the mercy of their landlords when it comes to efficiency. According to a survey by the US Energy Information Administration, an estimated 25 million low-income renters forgo food or medicine to pay for energy bills. Renters making under $15,000 per year spend more than 15 percent of their income on energy costs, compared with just 1.4 percent for households making more than $75,000. A well-insulated apartment with efficient appliances would not only slash a renter’s carbon emissions, it would free up money to spend on other necessities.

In California, dozens of cities have taken another approach to cutting carbon emissions: They have effectively banned new natural gas hook-ups. This has pushed homebuilders to use only electric appliances and heating, preparing homes for a carbon-free grid. Electric heat pumps, much improved in recent decades, can provide heating and air conditioning to these homes at a fraction of the energy use of conventional systems. And when powered by solar or wind, they have zero emissions.

But we can’t necessarily switch over to electric homes and call it a day. “These houses still use a lot of energy,” Goldstein said. When he and his colleagues analyzed energy use in 93 million homes across the US — 78 percent of the housing stock — they also modeled what it would take to reach the Paris Agreement’s goal of reducing emissions by 80 percent from their 2005 levels. Decarbonizing the grid and electrifying homes were a necessity. So, too, were other substantial measures.

Starting in the early 1980s, the median size of a new home has swelled from around 1,600 square feet to 2,300 square feet today.

For one, Goldstein said our homes should probably go on a diet. Starting in the early 1980s, the median size of a new home has swelled from around 1,600 square feet to 2,300 square feet today. In their paper, Goldstein and his coauthors recommend that houses slim down by 10 percent nationwide, returning the median size to what it was in 2001. Existing homes will need significant retrofits. In some places, communities will have to grow a bit denser and make do with fewer single-family homes. Goldstein’s recommendations for each state vary significantly depending on what their cities look like today. But nationwide, the changes are relatively modest: Hitting the Paris Agreement’s 2050 target will require just a 25 percent increase in housing density and a 3 percent reduction in single-family homes.

Packing more homes and apartments into smaller spaces might seem like a hard sell in the COVID-19 era, when space has become a luxury. But the pandemic may make some of the changes Goldstein is proposing a little more palatable. Extended families, now often scattered in large homes throughout the country, have been warming to the idea of multigenerational housing for decades, and despite the added difficulties of social distancing with multiple generations under one roof, 61 percent of the millions of Americans who moved during the pandemic moved in with a family member, according to the results of a recent survey. This not only brings families together, but it also helps lower everyone’s household footprint.

We might find a lesson in multigenerational housing’s continued appeal even in the face of a crisis: Climate-friendly housing may not look exactly like today’s homes and households. But in their own way, they’ll be better. And we’ll be better for it.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article here.

At any time around the world, countless people are flipping a switch, plugging in or pressing an “on” button. So how much electricity does humanity use? Learn the answer in this TED-Ed video: