Trying to understand what’s actually going on in the world’s climate seems like it might be truly impossible. For one thing, there are so many different factors at work. Everything from how light travels through the atmosphere to how the winds move the ocean around to how rain hits the ground has an effect on what actually happens on Earth both now and in the future. That also means there’s absolutely no use in looking at each piece individually … to understand what’s really going on, the climate jigsaw puzzle needs to be complete.

That, says climate scientist Gavin Schmidt, is where climate modeling comes in. The discipline synthesizes data from multiple sources, including satellites, weather stations, even from people camping in the Arctic and submitting measurements of the ice they see around them. Climate modeling, Schmidt says, gives us our best chance of understanding the bigger picture of the world around us. “We take all of the things we can see are going on, put them together with our best estimates of how processes work, and then see if we can understand and explain the emergent properties of climate systems,” he says. These four silent animations show what he means.

Cloud patterns over North America

[vimeo 93164059 w=500 h=281]

“This is a simulation of clouds over North America, taken from a very high-resolution climate model,” says Schmidt. His pithy description of this particular animation: “it’s dynamic, chaotic, and yet coherent.” Understanding and tracking the patterns within weather systems of the past means that scientists can experiment with what might happen in the future if you changed any of the contributing factors. “We’re trying to understand what happens to that chaos and dynamism and those patterns if you kick the system,” he says.

Watch particles swirl in the world’s atmosphere

[vimeo 93164060 w=500 h=281]

In this animation, different types of atmospheric particles are represented by different colors. “The easiest to see are the reddy-orange particles; those are dust, and you can see them streaming them off the Sahara,” says Schmidt. Also worth noting: white particles (pollution from burning coal and volcanoes); red dots (fires); and blue swirls (sea salt being whipped up into the air by the wind). “All of these particles in the air also affect the climate,” Schmidt says. Bringing together such disparate data in order to see how they all work together allows scientists to consider different future scenarios — and then plan for them.

Real vs. prediction: Watch the world’s climate change throughout the 20th century

[vimeo 93164875 w=500 h=375]

This animation shows what happened to the world’s temperature in the 20th century — alongside the best guess of a sophisticated prediction model. “Some things aren’t the same; there’s weather that’s different in both cases, and you do see slightly different patterns,” says Schmidt, but in the main he says he’s happy that the two turned out to be so similar, showing that the model is solid. Another lesson from this comparison of reality and a simulation model: “You do see climate changes emerging in both cases.”

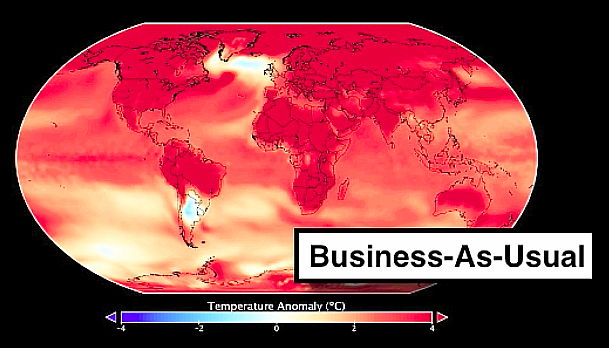

3 ways the climate might look in the future

[vimeo 93168472 w=500 h=375]

Here, compare three different climate projections. Says Schmidt, “we’re collectively making decisions every day that make one of those futures more or less likely.” Bottom left, how the world’s temperatures will change if we aggressively try to combat climate change; top, what happens if we work pretty hard; bottom right, what happens if we just keep trucking along as we are today (hint: a not-pretty blood red world, below). Why is this useful? “It’s important to note we do have an element of control,” says Schmidt. “For better or worse, we are masters of our climate destiny. There are choices to be made.” As for Schmidt himself, his dream is that in the future, climate change discussion will be a thing of the past. “I hope in 50 years’ time someone will ask, ‘What happened with climate change?’ and the answer is that we reduced emissions and it didn’t happen.” Is he optimistic this might actually happen? “Sometimes,” he laughs.