When the World Health Organization officially declared a pandemic on March 11 2020, the planet had already warmed by around 1.2℃ since pre-industrial times. However, the pandemic began a sudden and unprecedented drop in human activity, as much of the world went into lockdown and factories stopped operating, cars kept off the roads and planes were grounded.

There have been many monumental changes since then, but for climate scientists, this period has also brought some entirely new and sometimes unexpected insights.

Here are three things that we have learned:

1. The pandemic has not had a dramatic effect on climate change

In both the short and long term, the pandemic will have less effect on efforts to tackle climate change than many people had hoped.

Despite the clear and quiet skies, research I was involved in found that lockdown actually had a slight warming effect in spring 2020. Why? As industry ground to a halt, air pollution dropped and so did the ability of aerosols, tiny particles produced by the burning of fossil fuels, to cool the planet by reflecting sunlight away from the Earth. This impact on global temperatures was short-lived and very small (just 0.03°C), but it was still bigger than anything caused by lockdown-related changes in ozone, CO2 or aviation.

Looking further ahead to 2030, simple climate models have estimated that global temperatures will only be around 0.01°C lower as a result of COVID-19 than if countries followed the emissions pledges they’d already had in place at the height of the pandemic. These findings were later backed up by more complex model simulations.

Many national pledges have been updated and strengthened over the past year, but they still aren’t enough to avoid dangerous climate change. As long as emissions continue, we will be eating into our remaining carbon budget. In fact, the longer we delay action, the steeper the emissions cuts will need to be.

2. Climate science has adapted to operate in real time

The pandemic made climate scientists think on our feet about how to get around some of the difficulties of monitoring greenhouse gas emissions — and CO2 in particular — in real time. When many countries’ lockdowns were beginning in March 2020, the next comprehensive Global Carbon Budget setting out the year’s emissions trends was not due until the end of the year. So climate scientists set about looking for other data that might indicate how CO₂ was changing.

We used information on lockdown as a mirror for global emissions. In other words, if we knew what the emissions were from various economic sectors or from countries before pandemic lockdowns and we knew by how much activity had fallen, we could assume their emissions had fallen by the same amount.

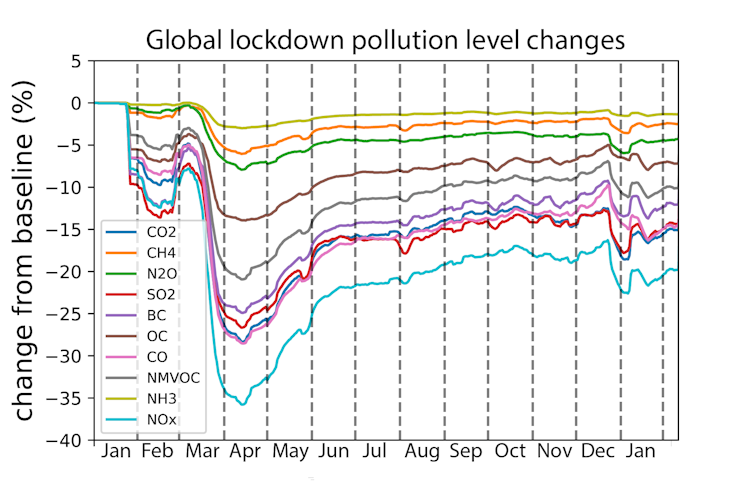

By May 2020, a landmark study combined government lockdown policies and activity data from around the world to predict a seven percent fall in CO2 emissions by the end of the year (a figure later confirmed by the Global Carbon Project). This was soon followed by research by my own team, which used Google and Apple mobility data to reflect changes in 10 different pollutants, while another study tracked CO2 emissions using data on fossil fuel combustion and cement production.

The latest Google mobility data shows that although daily activity hasn’t yet returned to pre-pandemic levels, it has recovered to some extent. This is reflected in our latest emissions estimate, which shows — following a limited bounce back after the first lockdown — a fairly steady growth in global emissions during the second half of 2020. This was followed by a second and smaller dip representing the second wave in late 2020/early 2021.

Image: Courtesy of Piers Forster

Meanwhile, as the pandemic progressed, the Carbon Monitor project established methods for tracking CO2 emissions in close to real time, giving us a valuable new way to do this kind of science.

3. Lockdowns can’t help save the climate

The temporary halt to normal life we’ve now seen with successive lockdowns is not enough to stop climate change, and it’s also not sustainable. Like climate change, COVID-19 has hit the most vulnerable the hardest. We need to find ways to reduce emissions without the economic and social impacts of lockdowns and find solutions that also promote health, welfare and equity. Widespread climate ambition and action by individuals, institutions and businesses is still vital, but it must be underpinned and supported by structural economic change.

My colleagues and I have estimated that investing just 1.2 percent of global GDP in economic recovery packages could mean the difference between keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C and a future where we are facing much more severe impacts — and higher costs.

Unfortunately, green investment is not being made at anything like the level needed. Many more investments will be made by governments over the next few months, and it’s essential that strong climate action is integrated into them. While the stakes may seem high, the potential rewards are far higher.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Watch this TED-Ed Lesson on what it takes to power the world now: