Physicians Raj Panjabi and Seth Berkley are on a mission to ensure that every person in the world has access to decent medical care. In a conversation, they discuss the obstacles standing in their way and the bold ideas that could help overcome them.

Around the world right now, more than one billion people don’t have access to basic health care. That means no checkups, no vaccinations, no medications, all because of the environment in which people live. They might be too poor to visit a clinic, or they might live too far from one, but the result is the same, and often fatal. It’s a problem that troubles many.

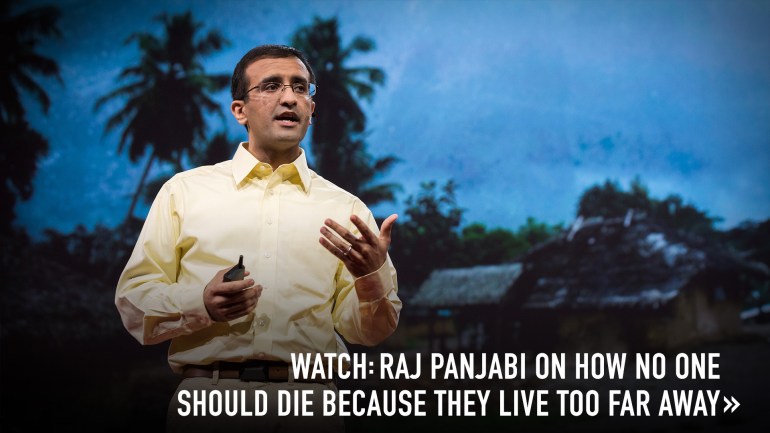

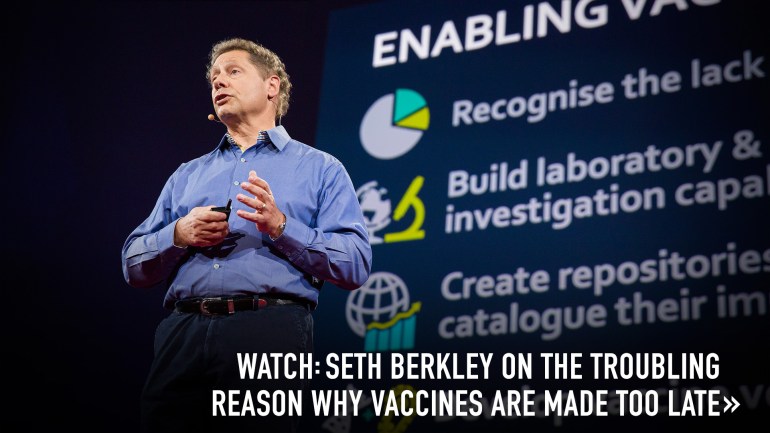

Take physician Raj Panjabi, TED Prize winner and co-founder of Last Mile Health, who trains community health workers to bring care door-to-door in remote communities in Liberia (TED Talk: No one should die because they live too far from a doctor). Or epidemiologist and physician Seth Berkley, who leads Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, an international organization that provides vaccines to children in the world’s 73 poorest countries (TED Talk: The troubling reason vaccines are made too late). Both are obsessed with the healthcare gap, and they recently connected over Skype to discuss it. We boiled down the chat into six smart ways to think about the future of global health care.

1. Think beyond conventional ideas of what a health care system looks like.

Good health care isn’t just about hospitals and clinics — or even just doctors and nurses. Good health care, Panjabi and Berkley agree, requires extending the reach of care directly into the homes of people in vulnerable communities. Training community members to be health workers is one of the best ways to do that. That’s how Last Mile Health works: Villages nominate community members for the program, and then outreach nurses train these people in 30 basic skills so they can diagnose and treat common ailments. Last Mile Health’s community health workers have already conducted over 100,000 patient visits in Liberia, and the organization is now supporting the Ministry of Health’s program to serve 1.2 million people by 2021.

“A lot of things doctors do can be done by less educated workers,” says Berkley, before trading impact stories of community health workers with Panjabi. In Ethiopia, for instance, community health workers have cut child mortality rates in half; in Pakistan, female health workers stepped in to provide care in a society where it’s taboo for men to treat women; in India, “Accredited Social Health Activists“ have transformed the well-being of people living in villages. The common thread connecting these workers? They’re professionalized. “For a long time, the philosophy was community health workers should be volunteers in poor countries,” says Berkley. “But this is a professional movement, with supervision and quality.”

Important to note: community health workers are not working alone. “We recognize they’re not going to succeed unless they’re integrated with the existing health care system,” says Panjabi. “In Liberia, nurses coach the workers and provide services alongside them.” If a community health worker suspects a more serious medical issue than they can treat, they connect a patient with a trusted doctor or nurse farther away. “It isn’t about putting health workers out there who aren’t connected to anything,” agrees Berkley. “You want them trained, you want them supervised, you want them to have referral systems, you want them hooked into supply chains, and that implies engagement with the government. Sometimes that makes it more difficult, but in the end, it’s the only way to take things to scale.”

2. Homegrown health workers provide a priceless benefit: trust.

During the Ebola crisis, Last Mile Health worked with Liberia’s government and several partners to train thousands of community health workers to tend to their neighbors. The workers helped stop the spread of the disease, while continuing to deliver care to children and pregnant women. In nearby Guinea, by contrast, some communities were hostile to the outside health workers who came in to treat them. In one startling case, eight health workers were killed by villagers who believed the workers were spreading the disease. Unlike the people in Liberia who followed health workers’ instructions, many people in Guinea hesitated to change traditional funeral practices like kissing the deceased, leading to widespread transmission of the disease.

The difference in the two countries: before the epidemic began, Last Mile Health had already established a baseline of trust by working on a super-local basis. Communities knew the workers who were coming to their doors. “I think one of the most under-leveraged tools in health care is the home visit,” says Panjabi. “When you recruit a neighbor, a relative, an already-trusted friend and bring care to the home level, powerful things can happen.” In southeastern Liberia, that helped the epidemic stay contained.

3. Local health workers can fill in critical data gaps.

Remote areas, say Panjabi and Berkley, are often blind spots for health statistics. While a national average might determine that 81 percent of children have been vaccinated, that figure can mask holes. In distant communities, the average might be 22 or even eight percent — or there might be no records at all. “Without having sub-national data, we don’t know where to focus. We can go to a country and say, ‘Your vaccination coverage is not good,’ but then where do you start?” says Berkley. To combat this information vacuum, he and the team at Gavi have requested that the World Health Organization start reporting its statistics at a district level.

So, how to collect this data? Community health workers can help. “They can be the trackers,” says Panjabi. As trusted sources, they can administer surveys and explain how the responses will be used — illustrating to people that they’re part of a bigger story.

4. Community health workers can play a key role in vaccine delivery.

Trust is also vital when it comes to vaccines. Community health workers are in an excellent position to combat fears and explain how vaccinations prevent children from getting a disease — and stop epidemics in their tracks. Local workers can also help solve another problem that’s often overlooked: vaccine delivery. While Gavi usually has enough vaccines available for diseases such as pneumonia, rotavirus and even Ebola (after a speedy campaign to develop and stockpile it), delivering them requires transport that can handle rough, off-road terrain, a “cold chain” (refrigerated storage from warehouse to truck to delivery site), and people who know how to administer the shots. “Connecting all these pieces is a challenge,” says Berkley. “You might have a refrigerator with no electricity, supplies with no refrigerator … But if you don’t have the health worker, forget the rest.”

Right now, because of local regulations, community health workers in most areas are not licensed to give vaccinations. But both Panjabi and Berkley think they could, if there were better systems to engage nurses in training and supervising them. Panjabi is using the 2017 TED Prize to build the Community Health Academy, a digital platform to modernize how community health workers learn. He sees enormous potential in collaborating with organizations like Gavi to create training tools and make sure kids get vaccinated safely and effectively. Panjabi and Berkley also raise the possibility of creating vaccination certification courses for community health workers and their supervisors.

5. Vaccinations forge connections between people and providers.

Vaccinations can be a gateway to reaching people who’d previously been excluded from health care. In 2015, for example, 65 million children received vaccinations through Gavi. Many vaccinations come in multiple parts, and each interaction gives caretakers and family members a chance to meet health workers. Gavi estimates that, in total, this can add up to 195 million points of contact with the primary health care system. “That’s an opportunity to reach not only the child but also his or her parents and siblings with other health services,” says Panjabi.“That’s extraordinary.”

Establishing good provider-patient relationships is essential. “When you have people connected to the system, it’s not only about delivering preventive care and curative care — it becomes your early warning system,” Berkley says. Some infectious diseases, like Ebola, first flare up in remote communities; if health workers are already there, diseases get noticed sooner. “The workers see their patients and say, ‘Oh, this is a strange disease. We need to investigate it, get samples to the lab and respond,’” says Berkley. “That basic system is just as important as isolation chambers and hospitals. Had that worked [with Ebola], there would have been small outbreaks. We never would have had it spread to urban areas and had bodies piling up in the streets.”

6. Powerful success stories can inspire and motivate others.

Last Mile Health and Gavi both partner with national governments, which are generally inclined to focus on serving urban areas due to their large, dense populations. But Panjabi and Berkley urge national public health officials to try thinking small instead. “We’re asking for a mental shift,” says Berkley. “Studies show that although it is more expensive and difficult to reach those living in isolated areas, you have a bigger effect.”

Last Mile Health shows how this approach can pay off on multiple levels. In a study of Konobo, one of Liberia’s most remote districts, community health workers linked with clinics boosted the care for children with respiratory infections by 51 percent, care for children with diarrhea by 60 percent, and maternal care by 40 percent in four years. While results like these are great because they mean many lives have been positively affected, they matter for another reason: they tell a story of hope. Demonstrating dramatic improvements in one place can inspire other communities and regions to participate. On a national level, small but powerful wins like this can spur governments and other organizations to launch larger-scale programs.

Hope is a powerful force, says Panjabi. “Once people stop seeing their kids die, all of the sudden things change. We’ve seen communities build clinics with their bare hands because they realize how powerful modern medicine can be.”