Decades before Twitter and Facebook, the Soviet state was a leader in perceptual manipulation technology. Meet the mighty flying propaganda machine of the 1930s: the Maxim Gorky.

One of Russia’s most prestigious cemeteries is set just south of downtown Moscow, adjoining a convent built in the 16th and 17th centuries. It contains the graves of Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol and even Josef Stalin’s second wife, who killed herself in 1932 and is commemorated by a wistful white sculpture. Of all the numberless monuments, headstones and columbarium plaques, among the most beguiling is an enormous relief of an airplane that is affixed to the crenellated brick walls. A tablet gives the name of this machine as the Maxim Gorky, and although I lived across the street for several years and must have seen the memorial half a dozen times, the aircraft is little-remembered in the West except among aviation and history buffs, and I couldn’t have said more than a few words about it until I came across it recently in a catalog I translated for a Moscow exhibition. The Maxim Gorky was, as I learned, considered an incandescent achievement of Soviet technology — and its story is particularly germane now.

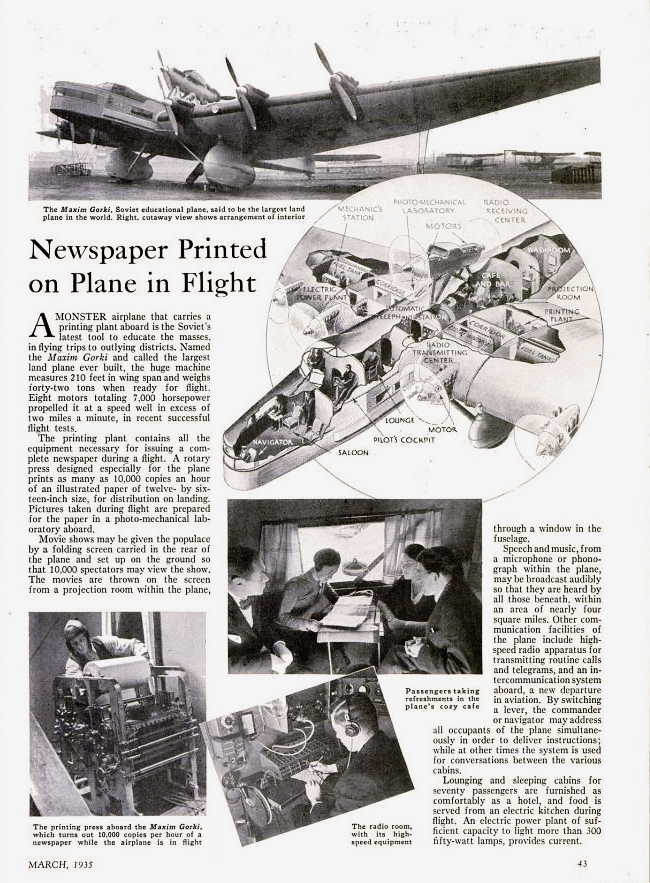

The state-controlled media in Putin’s Russia has won notice for the way it has cast the Kiev government, engaged in a conflict with pro-Russian separatists, in the worst possible light. But decades earlier, the Soviet state was a leader in this sort of perceptual manipulation. It invested enormous resources into its propaganda efforts, and in its formative years deployed the latest technologies to spread its message and glorify the Party. One of the most noteworthy examples was the colossal, eight-engine Maxim Gorky. It was created entirely for propaganda purposes and first flew in 1934. On board it carried its own printing press, and the plans called for a messaging system that a present-day observer calls “a prototype of Twitter.” (This is Ramiz Aliyev, writing in the catalog of the Moscow show, which was about artistic representations of aviation during the Soviet era; it took place at Moscow’s Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center.) There were even calls for the plane to beam slogans onto the clouds using a projector. The plane was described quite simply as a gigant, a giant.

The Soviet Union of the early 1930s, led by Stalin, was ragged and uneasy. In 1917, the communists had overthrown the government, prompting a civil war, but the country they seized was undereducated and underdeveloped. They enacted breakneck modernization plans, but were concerned about their hold on the peasantry, among others. The peasants were resentful for obvious reasons: Their harvests had been appropriated, leading to starvation, and they were forced onto collective farms. The Party also had an uncertain grip on the isolated and thinly populated regions of the Far North and Siberia. One of its responses was to hunt down opposition, both real and imagined, and by 1933 there were nearly 1 million people in forced-labor camps and colonies run by the secret police, notes historian Robert Service. Another was to amp up its propaganda.

It was natural that aviation should be the arena in which so many of these propaganda efforts played out. This was the airplane-mad era of Charles Lindbergh’s and Amelia Earhart’s record-setting flights. And aviation was alluring to Europe’s dictators, Scott W. Palmer, an expert on Soviet aviation at Western Illinois University, told me. Benito Mussolini took flying lessons. Adolf Hitler, at the beginning of the Leni Riefenstahl propaganda movie Triumph of the Will, is shown descending from the heavens in a plane. Stalin was portrayed as the father of his nation’s fledgling pilots.

The Soviets began a massive “aerofication” campaign and sought to copy America’s transcontinental air transport system, Palmer writes in his book on Soviet aviation. Between 1928 and 1932 the number of aircraft produced annually quadrupled, to around 2,500. Technology as a whole was fetishized in Soviet propaganda in this period — tractors and blast furnaces were exalted, and there were even “production novels” dedicated to construction projects — but aviation was at the pinnacle. “The airplane had emerged as the Soviet Union’s most prominent icon of progress and modernity,” Palmer writes.

The Maxim Gorky was the brainchild of magazine editor Mikhail Koltsov, who proposed building it to commemorate a literary anniversary of writer Maxim Gorky. (In the West, Gorky would later become notorious as the editor of a book lauding the construction of a canal that connected the Baltic and White seas and was built with forced labor, causing thousands of deaths.) The cost of the plane, first estimated at over 5 million rubles, was covered by public donations, and its design was based on that of Junkers aircraft from Germany, like many Soviet aircraft at the time. Construction began in 1933.

As described in Russian aviation specialist Maximilian Saukke’s 2005 book on the Maxim Gorky, the plans envisioned a printing press capable of producing 12,000 pages an hour, a darkroom, and a pneumatic post system and telephone switchboard for communications inside the aircraft. A loudspeaker system, named Voice from the Sky, would broadcast to people below.

Two other proposals were more fanciful. The first, which prompts the Twitter comparison, called for 18 illuminated letters to be affixed underneath the wings to beam messages from on high. Experts disagree on whether this was implemented. The other idea, voiced by A.A. Arkhangelsky, who ran a warplane division at the construction bureau responsible for the Maxim Gorky, was unrealized but is quoted by Saukke:

“Preferably during flight the plane will have the ability to show various images and slogans on the clouds or on a special smoke curtain created by the aircraft itself, by means of a special projector apparatus. These images and short slogans should be of a size that can be seen and read from the earth at a distance of around two to three kilometers.”

While the Maxim Gorky was being built, a propaganda squadron of smaller aircraft traversed the country. The Maxim Gorky, upon completion, was to be their flagship. The squadron touched down in towns and villages to deliver agitational messages and show movies. There are reports, says Palmer, of people camping out for as long as three days in subzero temperatures to get a glimpse of the aircraft. Pilots might take village elders aloft and point out to them that God was nowhere to be seen, helping to fulfill another Bolshevik goal, that of eradicating religion.

Admittedly the propaganda sheets that the squadron dispensed could be turgid and hectoring, such as one page proudly headlined “Thrown from a plane of the Maxim Gorky Propaganda Squadron.” Its author concludes a panegyric to the Revolution with an appeal for increased production of hemp products. But David Brandenberger, an expert in Soviet propaganda at the University of Richmond, told me that while the squadron may not have transformed the populace into dedicated Marxist-Leninists, it was persuasive in another way. Whether it was the flying machines themselves or the films they brought with them, “it’s going to produce a lot of people who at least have the impression that the Party is the bearer of progress and enlightenment.”

The public saw the Maxim Gorky for the first time on June 19, 1934, when it flew over Red Square for a celebration. While its reception among Russians was largely rapturous, this was not the case among foreigners. A U.S. Army assistant military attaché, quoted by Palmer, described it as “unbelievably ponderous in construction.” It was slow and had limited lifting capacity. In the end, it was something of a white elephant.

It seems clear today that the Maxim Gorky, and other contemporaneous aircraft garnished with superlatives, had a further purpose other than just impressing crowds or spreading the Soviet message, says John McCannon, an associate professor of history at Southern New Hampshire University. Machines that demonstrated a nation’s technological prowess could also send a warning to foreign powers, as was the case with Soviet aircraft that in this period were attempting to set polar flying records. “If I can fly a long-range bomber through the Arctic from Moscow and land in North America, as the Soviets did twice in 1937, that’s a signal I can drop bombs on Japan or Germany if I have to as well,” he said. In the Space Race, McCannon adds, the same idea applied to cosmic craft, which suggested their manufacturers’ facility for constructing intercontinental ballistic missiles. Today it’s not clear what Russia’s domestic propaganda efforts regarding Ukraine say about it, other than testifying to its capacity to construct a largely impregnable alternate reality.

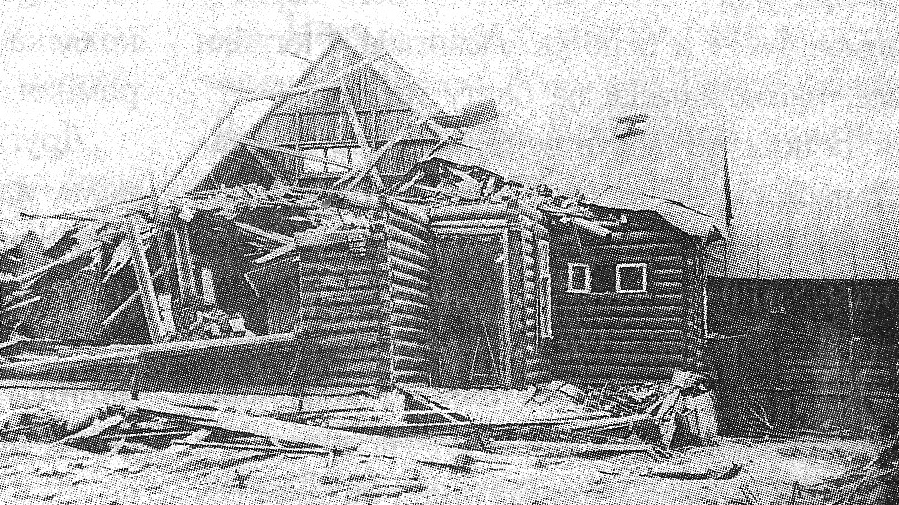

As for the Maxim Gorky, in 1935 it completed only 12 flights. On May 18, it was due to carry its builders and their families on pleasure trips over Moscow. Two smaller planes accompanied it, by their presence emphasizing the size of the flagship. An eyewitness, quoted in Saukke’s book, describes hearing music coming from the Voice from the Sky speakers as the planes passed overhead, and then seeing one of the fighters perform an aerial stunt — far too close to the larger plane. It crashed into the right wing of the Maxim Gorky and both planes fell to the ground in the suburb of Sokol, killing everyone on both aircraft, a total of 48 people. The pilot of the fighter, named Nikolai Blagin, was called an “aerial hooligan” by a Soviet defense official for trying to perform the maneuver so close to the larger aircraft. Nevertheless he was given an honorable burial. His memorial stone is near the relief of the supernally graceful-looking Maxim Gorky in the Moscow cemetery near my old apartment.

Featured image: Sailko/Wikipedia.