Making a giant, 8-foot-by-10-foot portrait of Edgar Allan Poe with thousands of earthworms was just as messy and complicated a project as it sounds, but it was also incredibly fulfilling. Here’s how — and why — artist Phil Hansen did it and what he took away from process.

For the past decade, artist Phil Hansen has been thinking about making art with worms. Yes, you read that correctly: Worms!

While working with worms would be unimaginable for many, Hansen (TED talk: Embrace the shake) has built his career out of making pieces with whatever captures his imagination. So he’s made art from banana skins, karate chops, and chewed food, among many other non-traditional materials. He’s also the current Guinness World Record Holder for making the largest connect-the-dots puzzle in 2017.

The idea of using worms first came to him following a summer rainstorm over 10 years ago. As he strolled through a wet suburb of Minneapolis (where he’s based), he noticed the many displaced earthworms. “As I’m walking along, I’m doing the typical thing you do after a storm comes along: dodging on the worms on the sidewalk,” recalls Hansen. “Also, what was happening is that I’ve worked with so many different art materials that I have this other part of my brain that is always looking for multiples of things. I was thinking maybe there’s a way to make art with the moving worms. I love to ponder those random little things.”

When he got home, he did what few would do: He grabbed chopsticks and headed back out. That evening, he carefully picked up about 150 live worms. “It was probably quite the visual for neighbors looking out the window,” he says.

By then, Hansen had thought about how he could make a picture with a live, moving material. “it turned into this idea of making a mold,” he says. “It’s actually really simple. You make a mold, you put the worms in it, you pull the mold away and then the worms are in the shape of the picture.” Picture a mold without a bottom — like a stencil that you can lift in and out.

To poke fun at the proverb “The early bird gets the worm,” Hansen created a picture of a bird by putting the sidewalk worms into a hastily constructed mold. He calls it “cliche and silly” but it helped him come up with a process for working with live worms in the future.

For years, the idea of working with worms on a larger scale existed only in his mind. Although he was eager to do so, he had to wait until he had enough — enough studio space, money, logistical support and time.

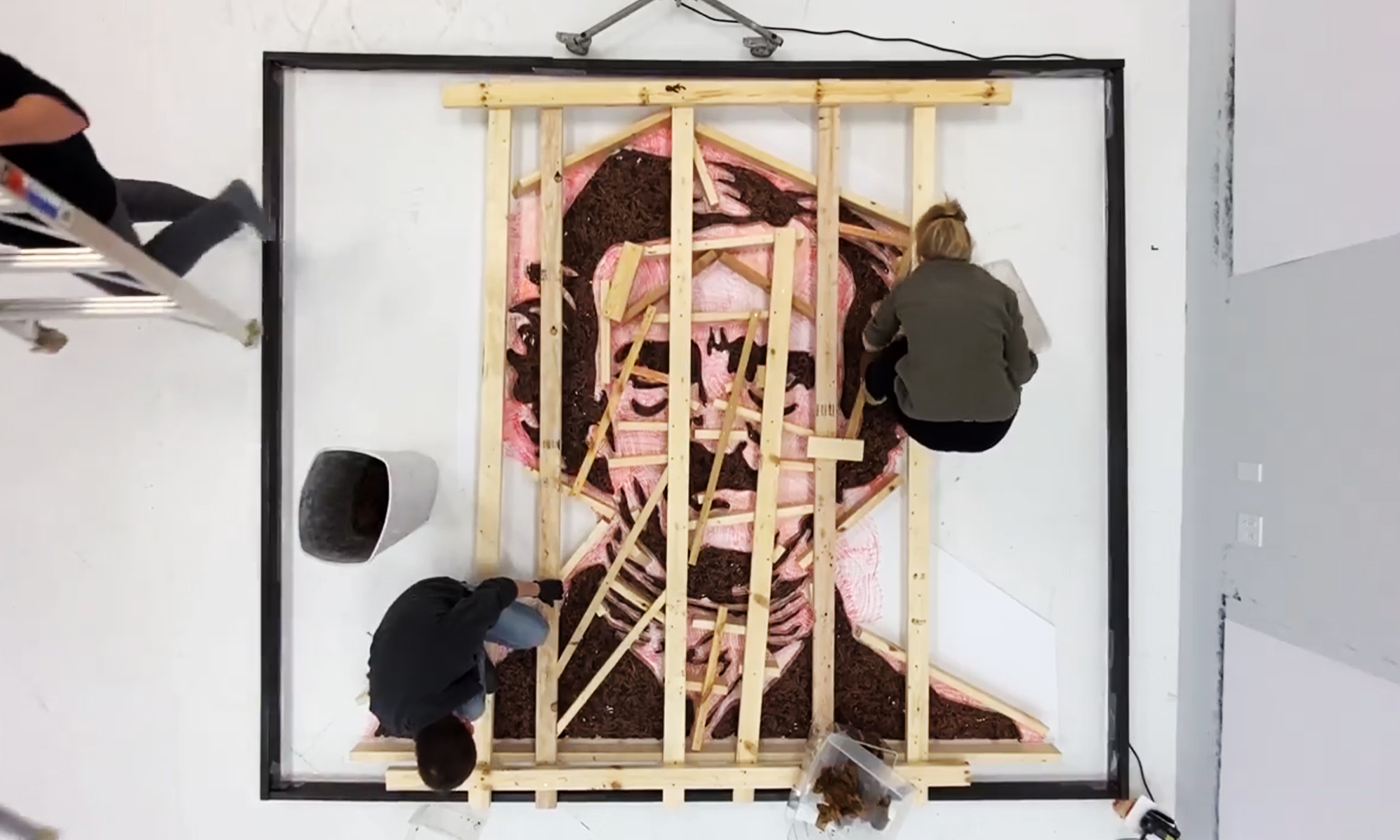

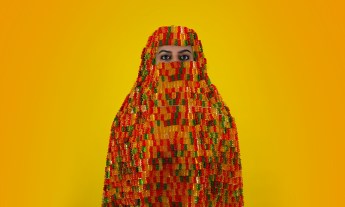

Last fall, Hansen garnered all the necessary resources and gave us what we never knew we needed: an 8-foot-by-10-foot portrait of Edgar Allan Poe made entirely from worms. Getting thousands of worms to conform to the shape and size of Poe’s head proved more difficult than the final portrait might suggest. Here’s a closer look into the intriguing — and, yes, kind of gross — process of creating the portrait and what Hansen learned along the way.

1. Let abundance inspire you

From burning matches to make an image of Jimi Hendrix and using 200 peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches to depict the Virgin Mary to arranging hundreds of baby doll arms and legs in the shape of “Octomom”, Hansen has shown that art can be made with just about anything — he just needs a big enough quantity of things.

“In life, we tend to see things in isolation; we see a singular of something,” Hansen says. “Yet when you see a multitude, it changes the experience. I’s lovely to see. Most of us have seen one or two worms here and there, but when you bring them all together it’s such a different visual. That plays out so much in life.”

Fun fact: Hansen originally planned to use thousands of worms to create a portrait of Kanye West. He thought it could be “entertaining and cool.” However, the idea slowly morphed into Edgar Allan Poe as a more fitting portrait subject. Poe, a 17th-century American writer and poet, is best known for his creepy contributions to detective- and horror-fiction, as well as his poem The Raven.

Hansen’s bird image was made from 150 worms; for this work, he would be working with many more multiples: 7,000 worms. But why 7,000? A test run using 500 worms barely filled Poe’s eye and part of his nose, so he knew he needed to scale way, way up. Hansen estimate he’d need 7,000 worms — and he ended up being right.

2. Making art is fun — but it takes lots of planning, time and labor

“Most people see art as enjoyable,” says Hansen, “and of course it is, but there’s also that side where it’s a lot of work.” After all, he couldn’t just dump worms onto the floor and command them to form Poe’s face. It took weeks of planning and preparation: around 200 hours. Meanwhile, making the actual picture took only about 10 hours.

Most of the work took place before any worms were even in the picture. Hansen started by sketching Poe’s face, using a portrait of the poet. But he wasn’t just copying what had previously been created. He had to draw the face with the appropriate level of detail so that it would still obviously appear to be Poe, even at an enormous scale.

So he distilled Poe’s facial features to their simplest form, rotated elements, and blew up the writer’s eyes so that they stared directly at the viewer. To determine the overall size of the portrait, Hansen scaled up based upon his face’s smallest feature — a fold near his eye. He used an old-fashioned projector to create a large version of his sketch which he traced onto foam core board.

After cutting the image out of foam core, he cut and glued plastic transparent sheets to create barriers preventing the worms from escaping. He hot glued, nailed, and screwed together wooden two-by-fours and made a giant frame so that it would be possible to pick up the mold.

Then came the worms. After visiting large outdoors stores, Hansen realized that they couldn’t provide him with enough. So, he turned to the internet, where you can buy anything — even thousands of worms. Five days later, a shipment of 7,000 worms — Canadian nightcrawlers to be exact — showed up at his studio.

When the worms arrived, they were covered in dirt and sediment. In what could have been an episode of TV’s Fear Factor, Hansen and a couple of his colleagues washed the worms — handful by handful — in water. Overall, it took them 18 hours to clean all of them. “Big piles of worms definitely are gross,” Hansen admits. “I feel like I’m one of the few people who has had that experience.”

They achieved their desired result: buckets of live, clean worms. But when Hansen and his team returned to put the worms into the huge mold for the portrait, the creatures were dirty again. As it turns out, they still had dirt inside them and were excreting it. After getting another bath, the worms were immediately dumped in the mold. The mold and frame worked just as planned: Poe’s squirming, writhing face emerged.

3. Art is about playing with people’s perception and perspective

To viewers, the finished artwork would appear to be that large picture of Poe’s face. Unsurprisingly, Hansen has a different view. He also made a short film of the piece that showcases the different steps and perspectives that went into the portrait, and he considers that to be an important part of the project.

“I tend to like art where there’s different ways of looking at it,” he says. The video offers just that.

When the camera zooms in, Poe’s face falls away and all that can be seen are the layers of worms wriggling together. According to Hansen, “there’s some aspect of humanity in there. How you look out at a sea of people, and we’re all just kind of doing our own thing going this way and that way.” When the camera zooms out, the worms recede and Poe’s face returns.

What does Hansen want people to take away from his project? He says, “Of course, I want people to laugh and be entertained. I [also] want people to consider the small things in life and look at them a little bit differently. Almost all of us have had that experience of seeing worms on the ground as we’re going on a walk.” His portrait could drive us “to just look at that experience in a new light.”

For Hansen, his work is also about shining a light on the artistic process. “Most artists, generally speaking — and I’m guilty of it too — want to maintain a little bit of mystery,” he says. “You don’t show all the steps because it’s fun to have people just see the ‘wow’ factor at the end, to not know the very boring, straightforward steps that you took to get there. ” In the video, he shows us some of the prep work, such as building the frame and dropping the worms into the shape of Poe’s face. By including the more mundane details and exposing his process, Hansen is changing viewers’ understanding of what art is and perhaps adding back some “wow” to the labor behind it.

4. Making art isn’t only about the before and during — it’s also about the after

After Hansen lifted off the mold, he let the worms wriggle around for about 6 hours. As time elapsed, the worms shifted and so did Poe’s face. Hansen did not show or exhibit the work to the public. Other than his colleagues, no one else really saw the finished product in person.

Even after the difficulty of making a portrait from living worms, Hansen was left with a greater task: “treating the worms decently,” as he puts it. He calls this the most challenging part of the project. What does one do with 7,000 live worms? Actually, it was 6,997 worms (three worms were accidentally crushed by the frame).

Unfortunately, he had no easy solution. While earthworms inhabit Minnesota, they’re actually not native to the area (and other parts of the northern US, for that matter). In fact, many earthworms in the US are species that can be traced back to Asia and Europe. In Minnesota, anglers are advised against throwing worms in the water after using them as fishing bait, according to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Still, he couldn’t fathom killing the thousands of worms that created his art. He released them in a wooded area right behind his studio.

5. Get comfortable with letting your ideas — and your career — evolve

In reflecting on the Edgar Allan Poe piece, one of Hansen’s main takeaways is to hold onto ideas, even if you think they are bad at the time. His advice: “Never take what appears to be sh**ty idea and completely get rid of it.” He explains, “We need to let those ideas sit in us and develop, and sometimes they’re not ready for prime time, and that’s okay. Just let ideas evolve.”

He initially deleted his early experimental video of the bird made from 150 worms. He thought it lacked meaning and nuance. But he kept the idea and it eventually evolved into his portrait of Poe.

In addition to letting his ideas evolve, Hansen has also become open to evolution in his career. He says, “I feel like anyone who makes a career in art always kind of finds their own path.” While he started out thinking of his art as something to be displayed on the walls and floors of galleries and museums, he has come to embrace it being exhibited to the public via YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Today, Hansen’s pieces don’t fit into a box — literally or figuratively, and he’s not sure how to classify his work. “I don’t think I would call myself a video artist, but I do feel like I’m crossing over where with more and more of my work, the permanence of it is completely irrelevant.”

Hansen typically works on five to six different projects at a time. One project that he’s particularly excited about involves working with urban gardener and TED speaker Ron Finley (TED Talk: A guerilla gardener in South Central LA). “Finley is giving artists regular old shovels to paint on,” Hansen explains. He spoke to Finley at the 2019 TED Summit, and “I was, like Ron, ‘Could I use the shovel to paint’?” Ron agreed, and next up, Hansen will employ a shovel as a paint brush. Wait, what? We can’t wait to see what he creates.

Watch his TED Talk here:

Watch this TED-Ed lesson to learn more about Edgar Allan Poe: