After a long career as a game designer, Brenda Romero became an educator — teaching the next generation of artists, coders and mechanics how to create the world’s most popular media form. A game is the tool she uses to think about problems, to explain, to put concepts into form. As she says: “This is all I’ve ever done. I’ve been a game designer since I was 15 and this is my natural way of seeing things.”

In 2008, she began a design exercise that expanded into a series called “The Mechanic Is the Message” — analog (not video) games that use game mechanics, boards, pieces, and rules to help a player think through hard problems. Her game “The New World” was an attempt to explain U.S. slavery, and the experiences of the people caught in it, to her young daughter. “Síochán leat” (Gaelic for “peace be with you”) explores the complex history of Ireland and the Irish diaspora.

In her TEDxPhoenix talk, given in 2011, Romero mentioned a new game, an intriguing protoype called “Mexican Kitchen Workers.” We asked her to tell us more, and in an hour-long phone call while driving on Hwy. 17 on the way to her office in Santa Cruz, she did. The conversation has been lightly edited.

What was the genesis of Mexican Kitchen Workers?

“I was meeting with a client in Columbus, Ohio, and he was a restaurant owner. He was talking about the employees in the front of the house and how entitled they were. “They want this… they want that…” Somehow I knew that everybody he was referring to was white. And then he said, ‘On the other hand, take my Mexican kitchen workers …’ and it was like, if these words that came out of his mouth could float up and become illuminated — !

It was such an odd phrase that meant so much. So I started breaking into restaurant kitchens to find out who was in them. I’d say, ‘Oh I’m just going to use the restroom, and by the way can I see your kitchen?’ And they were filled with Mexicans, no matter where I was in the country. In kitchens, Mexican workers are seen as a disposable resource. As a restaurant owner, if somebody calls the INS and reports undocumented Mexicans, you kind of don’t care. The fines are not substantial enough to stop you. The person most hurt by it is the worker who might get deported. Treating your employees as a disposable resource actually means disrupting their lives, deporting their children.

The economics of it came about because U.S. subsidies on vegetables created this tremendous disparity in Mexico. Meanwhile, the U.S. demand for drugs created a tremendous culture of violence in Mexico. The demand that the Mexican government ‘do something’ about drugs creates instability. So people cross the border not only for work, but just to be safe.”

How the game works

How the game works

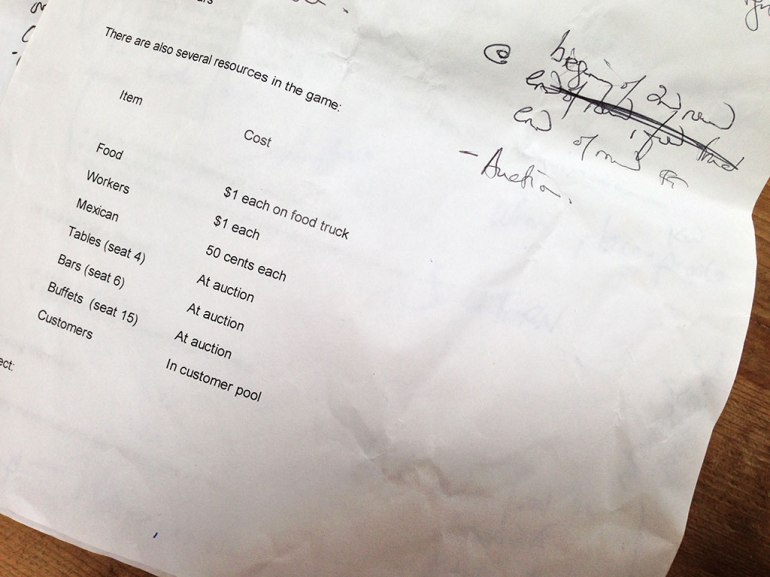

“There are five players and they’re all restaurant owners. The rules are modeled on real-world economics. Which means that if one of us chooses to use illegal, undocumented labor, price-wise we will destroy everybody else.

In its fourth iteration now, the game is looking at this system that propagates disparity because it needs to, while externally talking about how it’s all wrong. It’s a system that is blind to its brokenness. It’s a system that requires disparity.

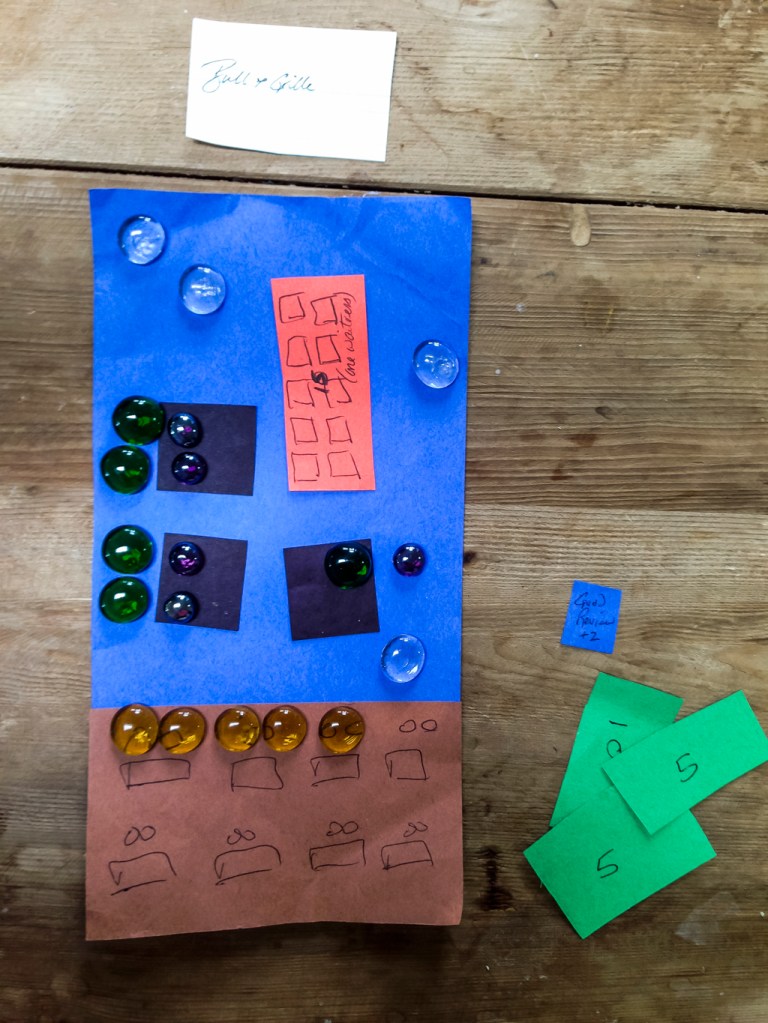

In play tests, some really unique things happened, right from the prototype. I had glass beads out, those flat marbles you use in vases with flowers, and people just naturally picked up brown ones to go in the kitchen, which was horrifying. They picked up the clear beads to be front of house.

The one point in the game that really bothers me is the disposable nature of the workers when they’re represented by game pieces. This isn’t like Monopoly, where you get a fake $200 bill or four houses. I’m exploring using real people in the game, so that when you hire them you see these real people — not resources, but real people with real lives. If I use real people, I would probably have them waiting around on chairs, just standing in small groups like the guys standing around in front of Home Depot. It should reflect reality — you’re not pulling them out of a bag. I want people to leave this game having a feeling for the actual people behind the system. We see the system as way too abstracted. We caused this problem, it’s because of us.”

The one point in the game that really bothers me is the disposable nature of the workers when they’re represented by game pieces. This isn’t like Monopoly, where you get a fake $200 bill or four houses. I’m exploring using real people in the game, so that when you hire them you see these real people — not resources, but real people with real lives. If I use real people, I would probably have them waiting around on chairs, just standing in small groups like the guys standing around in front of Home Depot. It should reflect reality — you’re not pulling them out of a bag. I want people to leave this game having a feeling for the actual people behind the system. We see the system as way too abstracted. We caused this problem, it’s because of us.”

A game about the complex economy of a slum

“The other game I’m working on is called Cité Soleil. It’s about life in a slum of Port au Prince, Haiti. By American standards, Port au Prince is a slum, so this is the slum of the slum. I’m not sure I can pull this off, but I think I can.

It is two games with two different rule sets, two different groups of players and two different goals played on the same board with the same pieces at the same time. It’s complex, but it is an accurate reflection of life in Cité Soleil and the complex economy that exists between people just trying to get by and those trying to maintain political pressure for those in power.

I’ve seen situations of power from both sides and the economic disparity they create. It’s either economic disparity or greed that sets the abhorent situation in motion. And then I make a game about it.”

Motivating factors

“When I was just doing these as design exercises, I wasn’t planning on turning them into a calling. But now I really feel what this is what I am supposed to do. I just gave an hourlong talk at Berkeley about the series I’m working on — they elicit tears from people in the audience. Which is not something I expected, but I’m obviously sitting pretty close to home with some of these issues.

I’m knee-deep in the Trail of Tears right now, for my game ‘One Falls for Each of Us,’ which looks at Native American issues. I was recently invited to speak by two native groups. I’ve never been invited to speak at a native event ever, so something is falling into place. This is where my heart lies.”

[ted id=1432]