Ancient Peru was home to many cultures, most of them still quite mysterious to modern archaeologists. But as Sarah Parcak directs her citizen-science platform at the Peruvian landscape, the invisible past could make a comeback.

A mummified macaw with orange and blue feathers. The body of an ancient priestess, whose arms and legs were covered in tattoos. A large sculpture in the shape of a face (which looks a bit like a frown emoji).

These objects have been unearthed by archaeologists in Peru in the past decade years alone. The arid cold of Peru’s highlands and the dry heat of its coastal desert do an incredible job preserving artifacts — just one reason that Sarah Parcak is excited to turn her attention to the South American country. A pioneer of “space archaeology,” Parcak and her team analyze satellite imagery to identify possible ancient human sites that are otherwise hidden from view. Parcak’s work has gained her much acclaim, but this time, the project is no longer hers alone. With the TED Prize, Parcak has built a citizen science platform, GlobalXplorer, to let anyone with internet access try a little space archaeology in their spare time. Peru is the first country users will search.

It would take archaeological teams working on foot several lifetimes to survey all of Peru. With the power of satellites and the crowd, it could happen in a matter of months. Why Peru? Three reasons, says Parcak. First: the ideal past. While people are familiar with the Inca and Machu Picchu, Peru is home to archaeological sites from many different cultures in many different time periods. Second: the ideal climate, mentioned above, which has preserved the past so well. Third: the ideal timing. The Peruvian government is highly motivated to curb the looting of cultural artifacts, but needs data to fuel their efforts.

Below, a look at some of Peru’s ancient cultures, along with the big questions archaeologists still have about them. There’s a chance that new sites found with GlobalXplorer could offer new clues in solving these mysteries.

Peru’s early cultures, sharp timekeepers. In 2006, archaeologists uncovered an ancient astronomical observatory just a few miles outside Lima, with the aforementioned frowning sculpture inside. This ancient temple dates back 4,200 years, and on December 21 and June 21 — the solstices, which mark the beginning and end of the harvest season — it would align with the sunrise and sunset. The site was built by one of Peru’s pre-ceramic cultures, which dotted the landscape from about 3000 to 1800 BC. The site suggests that their artistic skill and scientific understanding were way ahead of what we previously assumed.

In 2007, another site pointed to ancient Peruvians’ penchant for time-keeping. The Thirteen Towers of Chankillo — a series of pillars, each 7 to 20 feet high, almost like Stonehenge in a straight line — showed the sun’s position throughout the year. A long corridor funneled viewers to the right spot for observation. Could these pillars have inspired the Inca, who also tracked the movement of the sun?

In their report, the archaeologists who found the 4,200-year-old temple noted their luck, as treasure hunters had dug a 20-foot hole right above the site. The temple could have been found and stripped clean. With each object looters take, they undermine our ability to understand the people who created a site. Chase Childs, project manager for GlobalXplorer, says this means the race is on. “Looters are doing a great job of uncovering these sites,” he says. “There’s real urgency.”

What are the Nazca Lines about? An owl-like figure carved in a mountain. An enormous spider in the desert. A monkey with a spiraling tail. When commercial airlines began flying over southern Peru decades ago, people started noticing these ancient geoglyphs — now known as the Nazca Lines, for the Nazca culture that lived there from 100 to 600 AD. The Nazca-Palpa Project has done a long-term study of these lines, and their research suggests that they were pathways for ceremonial processions, perhaps intended to bring renewed water. The Nazca may have found these ceremonies increasingly important as their region changed from a river-rich delta to one of the driest places on Earth.

But a newer discovery offers another possible explanation. In 2014, archaeologists studied similar lines created by the Paracas, a culture that collapsed around 100 BC and gave way to the Nazca. Some Paracas lines stretch for nearly two miles, and archaeologists believe they were created to point people coming down from the highlands toward trading posts. Like billboards on the highway, the lines might have gotten longer and flashier as trading sites competed.

Nazca sites are in danger too. “There’s a lot of illegal mining going on,” says Parcak. Childs adds that because the area is isolated, it’s especially susceptible to looting. “When you look at [satellite imagery] of this region, you can see entire towns that have been looted. Imagine all that history, gone,” he says. But satellite images are revealing potential new sites. “That’s with four of us looking for a couple of days,” he says. “Imagine setting loose 10,000 people and having them looking for months.”

The mysterious priestesses of the Moche. The Moche thrived in Peru from 200 to 850 AD, and are known for their beautiful pottery and giant adobe mounds, with intricate wall murals inside. One major theme running through their art? Human sacrifice, with goblets of blood being offered to the gods. Archaeologists have debated whether the Moche sacrificed elites to ensure prosperity, or if their sacrifices were more about war as cities vied for power. Recent evidence suggests the latter. In 2013, archaeologists analyzed oxygen isotopes found in the remains of 34 Moche sacrifice victims, to determine where they had lived. The results showed that, over time, the victims came from further away, suggesting conquest.

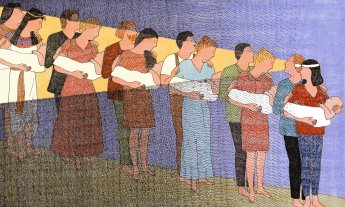

Another mystery of this culture: what role did female elites play? Archaeologists have uncovered tombs of women who seem to have been priestesses or queens — or both. In one case, a woman’s skeleton was found in a red tomb, with a copper mask and sandals. She was raised on a platform, surrounded by the bodies of sacrifices. A tall silver goblet stood beside her — the same kind shown in Moche art. In another tomb, a 1,500-year-old female mummy was found with a cache of gold objects and fine weapons, symbols of power you wouldn’t necessarily expect to see buried with women. Unwrapping this mummy took months, and when archaeologists finished, they were surprised to find the woman’s arms, legs and feet covered in tattoos — some of geometric patterns and some of animals.

New Moche sites may make these practices clearer. But finding these sites will be a challenge, as the Moche used mud bricks that don’t show up as well in satellite imagery. “They’re earth-built structures, so they won’t look like buildings,” says Childs. “What you’ll be looking for is some kind of visible change in a landscape. You’re going to look and say, ‘Is that bump just a hill, or is it manmade?’” GlobalXplorer users will get a field guide with examples of structures from all these cultures, so they can give an informed opinion.

The Sicán, an ancient water cult. In 2011, archaeologists found the tomb of a Sicán priestess buried with eight corpses, possibly intended to accompany her into the afterlife. The finding was fascinating — but not as interesting as what the team discovered a year later when they dug below. Here, they found a basement tomb, built to flood with water. They found four waterlogged bodies inside — one of them wearing pearls, turquoise and beads, and covered with a copper sheet with a wavelike pattern. The Sicán lived along the Peruvian coasts from 800 to 1375 AD and have been characterized as a “water cult.” According to legend, the Sicán believed themselves to be descendants of Naylamp, a god who emerged from the sea and walked ashore on crushed shells. Ancient ceremonial knives show Naylamp sitting cross-legged on a throne. In 2010, archaeologists excavated a Sicán temple and found a throne identical to the one Naylamp sits on in their iconography. The finding suggests that Sicán rulers may have considered themselves demigods. But the flooding tomb? Indiana Jones fans might suspect it’s a booby trap, but experts think the burial at sea could be related to renewing water during a drought, or attached to ideas of the ocean as a space of rebirth.

We’ll need new sites in order to understand. Childs stresses that it’s not just artifacts that tell the story of a people. “Archaeologists are rarely interested in pretty things,” he says. “It’s, ‘Where was this pot found? What was inside it? Was it buried with someone? Was there a particular orientation?’ These things can tell us something about religious beliefs.”

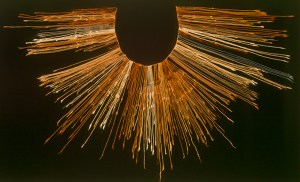

The unusual records of the Inca. The Inca ruled Peru from 1438 to 1532 AD, and their cities still inspire awe. “They were incredible architects,” says Parcak. “They selected stones like puzzle pieces, and then pounded them together so they fit almost perfectly without mortar.” Interestingly, however, the Inca didn’t keep written records. Instead, they used quipus, an intricate system of colored and knotted strings. Experts today are baffled by them. They could be a record-keeping system, with knot placement denoting numeric value, or they could be a set of coded histories. Archaeologist Hiram Bingham, who located Machu Picchu in 1911, spun a fascinating tale about them in his book Inca Land. His story takes us to Tampu-tocco, a mythic origin city, akin to a Garden of Eden, from which the founders of the Inca empire emerged. According to Bingham, a soothsayer at Tampu-tocco believed that the gods disapproved of the invention of writing. So the king forbid it. Quipu rose up in its place.

In 1913, Bingham wrote in National Geographic about the excitement he felt when, “beneath the shade of the trees, we could make out a maze of ancient walls.” Though the locals called the place Machu Picchu, he was convinced he’d found Tampu-tocco — an idea long since rejected. Today, many think Machu Picchu was a sacred retreat, many think it was a royal estate and many think it was both. It’s unlikely GlobalXplorer users will locate an unknown site of its scale, but there could be noble estates or farmsteads out there. “Hopefully, we find cool stone buildings on top of mountains,” he says. “We may see stone construction on an exposed face that’s really isolated, or that’s been missed because you can only see it from a top-down perspective.”

It’s ironic — the high-tech, remote nature of all this searching may make Parcak’s work seem like a far cry from the days of Indiana Jones-style archaeology. But the urgency she feels to find ancient sites before looters do is the same kind of race against time that fuels every good Tomb Raider narrative.

Parcak doesn’t have the time to appreciate the irony, though. Her ultimate goal in Peru isn’t just finding these sites, but helping create a model for how a country’s ministry of antiquities and local populations can take ownership and responsibility for preserving ancient sites. The sites of all these cultures are in grave danger. “We don’t just want to find sites to say we found them,” she says. “We also want to find ways to help protect the cultural heritage we all share.”

.

Sarah Parcak’s GlobalXplorer invites the world to help locate and protect ancient sites. DigitalGlobe has the provided satellite imagery; National Geographic Society has contributed rich content and exploration support; archaeologist Luis Jaime Castillo Butters serves as co-lead investigator in Peru; and the Sustainable Preservation Initiative will support communities around sites. Start exploring »