Matt Kenyon’s art doesn’t just cast a sardonic eye on the systems around us, it also infiltrates and subverts them. He walks us through some of his projects.

Wickedly funny and infused with technology, the work of Matt Kenyon makes you stop, makes you think. His culture-jamming, interactive works enlighten, startle and often make shocking use of his own body. As cofounder of the Interventions in Capitalism research group at RISD and cofounder of SWAMP (“Studies of Work Atmospheres and Mass Production”), Kenyon (TED Talk: A secret memorial for civilian casualties) is always pushing forward his mission to use propaganda as a starting point for cultural subversion. He shares the evolution of his artistic practice.

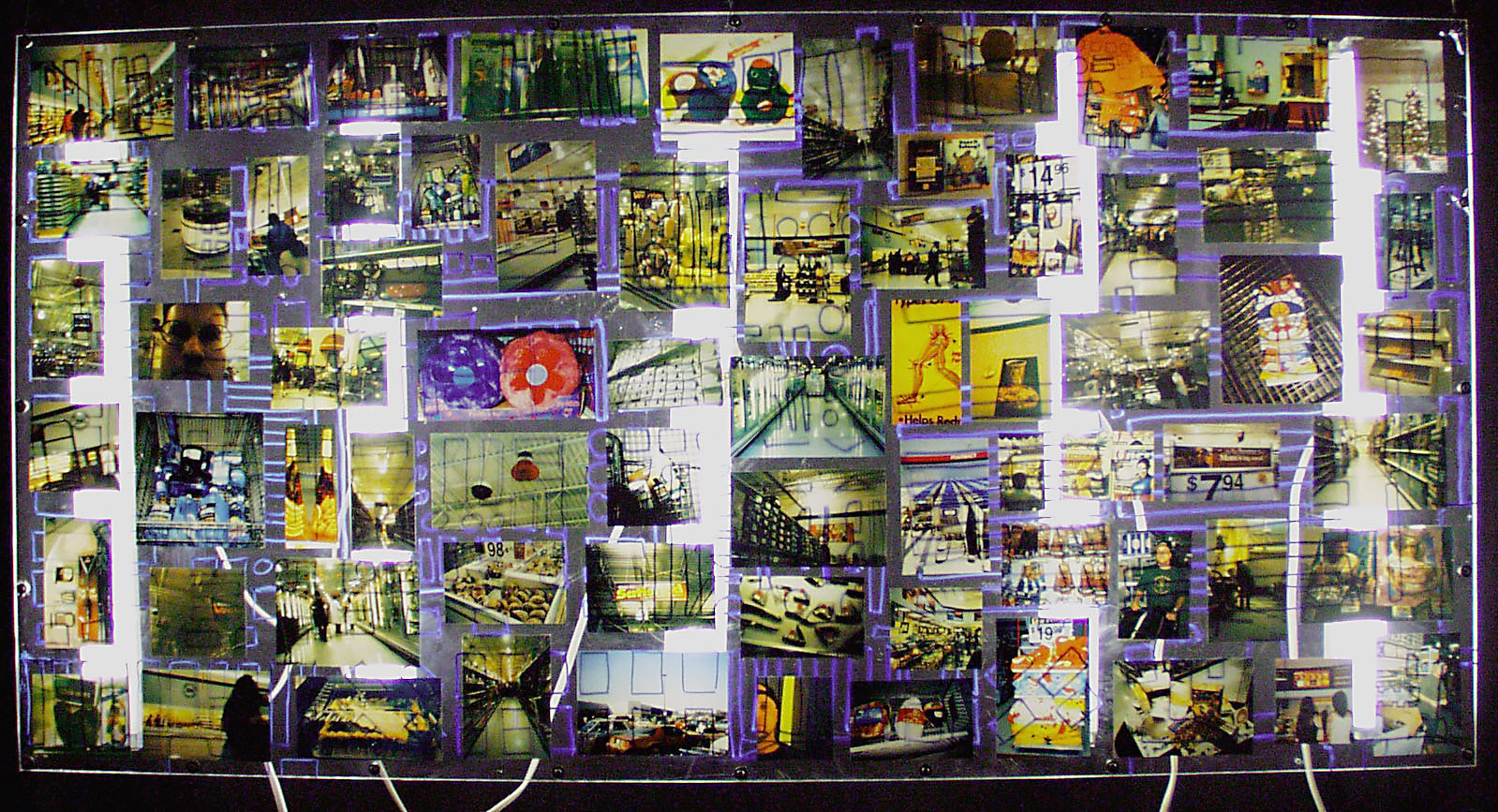

Eat, sleep and breathe Walmart

In Walmartathon (2001), Kenyon and his collaborator Doug Easterly moved into the Walmart in Hammond, Louisiana, for 24 hours, wearing only Walmart clothes, eating only Walmart food, and documenting the experience. “When you’re not looking to buy things, the space becomes overwhelming and somewhat terrifying — but it did teach me a lot about how such spaces play different roles in the life of a town,” says Kenyon. “In the morning, senior citizens would come in and get their free cup of coffee, and they’d use Walmart as place to walk around in for exercise. Later in the day, teenage couples would come and act out the process of shopping. It was a more socially complex experience than I’d imagined.”

The improvised empathetic device

Kenyon’s father and stepfather both served in Vietnam, so he is acutely aware of the toll war takes on humanity. In 2006, seeking more than skin-deep empathy for those dying in the war in Iraq, he devised a black armband wirelessly connected to a data scripting program that received, in near real time, US government casualty statistics. The so-called Improvised Empathetic Device was modeled after real improvised explosive devices that use cell phones or pagers to trigger relays that connect to bombs or shells. “The armband would display the names, ranks, cause of death, and location where the person died — then stab me in the arm with a needle, once for each soldier who died,” says Kenyon. “This became a way of internalizing data, instead of just knowing it intellectually, though of course the pain is nothing compared to the pain that soldiers’ families and friends feel at the loss.” (Watch the video of this project.)

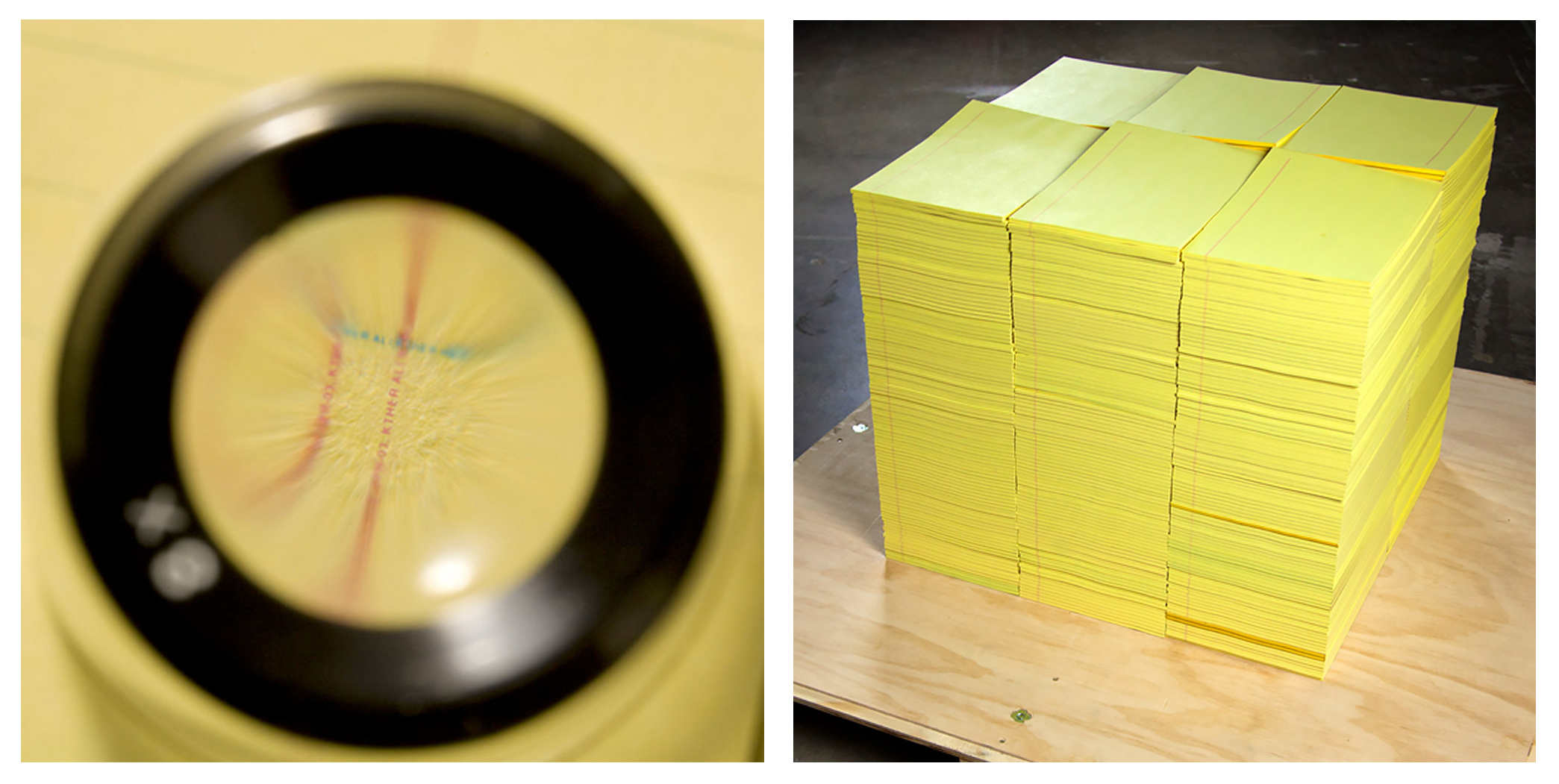

The notepad of casualties

For every soldier who died in the Iraq war, thousands of civilians were dying. This led Kenyon to develop a yellow notepad, printed in microtext with the names, locations and dates of more than 100,000 Iraqi civilian casualties. Conceived in 2007 as a memorial to the civilian life lost during the ongoing Iraq War, and in response to the vast discrepancy between Iraqi and US casualties, Kenyon at first surreptitiously distributed these notepad memorials, smuggling them into Capitol Hill via office supply channels. Later, he began distributing the paper to the general public, asking citizens to use it to send letters to government officials. Each piece of American government correspondence is archived in the Library of Congress, so Kenyon’s monument not only infiltrated the White House; it became part of the nation’s permanent historical record. He also presented the Notepad memorial to the politicians who led nations to war, including former US Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. The response? “He just said, ‘Thank you,’ and had his men escort me away,” says Kenyon. (Watch the video of this project.)

Chewing and chewing (and chewing) a Big Mac

In response to a stunt in which McDonald’s gave out pedometers with adult Happy Meals, Kenyon built a machine that forced him to chew for the amount of time it would take to burn off the 560 calories in a Big Mac. “Instead of changing the quality of the food that they sold, McDonald’s gave out a device and put the onus for good health on the consumer,” says Kenyon. “Meat Helmet was a farcical machine that harnessed chewing as a form of aerobic activity.” Incidentally, it took Kenyon eight hours of chewing to burn off all 560 calories. “It’s been the most damaging thing I’ve done to my body so far,” he says. “I became a vegetarian for two and a half years after that.”

A noxious puddle of goop

For Puddle, Kenyon created a piece that looks, at first, like an ordinary puddle of oil (actually ferrous liquid). Then, words related to western expansion, manifest destiny, First Nations people and car culture appear to rise out of the gloop. Many of the words, like “suburban,” “sequoia” and “Tahoe” fit all three categories. Others, such as “discovery,” “avalanche” and “expedition,” refer to American frontier mentality. Put together, the pieces highlight the inherent contradictions of vehicle branding; Kenyon’s take is that the very automobiles that celebrate rugged individualism also shackle Americans to a cycle of resource dependency. “These off-road luxury vehicles rarely see the environs they claim to represent,” he says. “Meanwhile, they pose one of the greatest threats to our environmental well-being.”

A fracking tap

Created with the architect Adam Fure, the 2016 project Tap is a sink installed into a gallery wall. A bright flame spouts from its faucet, a reference to an image that has become synonymous with fracking. In the piece, the flame “speaks,” telling stories about fracking pulled from personal accounts of landowners, truck drivers and a sampling of mass media coverage of the issue. “The flame is specially modulated by high-voltage electrical fields so that it operates as a loudspeaker,” says Kenyon, who first became familiar with fracking’s environmental and political controversies while living and teaching in central Pennsylvania. “I was partly inspired by a photo of a burning river from the 1960s,” he says. “Images have power. The photo of the burning river helped galvanize public support for a series of ambitious pollution control activities, eventually resulting in the Clean Water Act and the establishment of the federal Environmental Protection Agency.”

Ever-decreasing fossil fuels

For the 2014 project Supermajor, Kenyon designed a wire rack of vintage oil cans, one with a visible fissure out of which oil slowly flows, appearing to cascade onto the pedestal and the gallery floor. When you look closely, though, the oil is actually moving backwards into the can — a critique of humanity’s unreasonable faith that the abundance of fossil fuels will, against all evidence, go on indefinitely. “The saying ‘What goes up must come down’ can be applied to a variety of things — from a ball thrown into the air to a stock market which cannot continue to rise forever,” says Kenyon. “All good things must come to an end.” Named for the oil cartels of the 1940s to the 1970s, Supermajor was recently defaced while on display in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Says Kenyon: “The gallery staff swapped out the Exxon, Shell, BP and Mobil labels on the oil cans for Petronas labels — overnight and without my knowledge or permission.”

A giant pool of money

Kenyon’s Giant Pool of Money series examines the thoughts and beliefs that led to the global financial crisis in 2008 and the profound loss of faith in markets that followed. The centerpiece of the series is a 15-foot-tall pyramid of champagne glasses, connected to a change machine that breaks dollar bills into “quarters.” The coins were actually replicas minted by Kenyon out of the element gallium, a metal that melts just above room temperature. Transported by a network of conveyor belts to the top of the pyramid and deposited into the uppermost champagne glass, the coins melt and cascade down the pyramid over time. (Watch the video.) It’s equal parts literal trickle-down theory and Terminator 2’s liquid metal monster. “I ask viewers to feed paper money into the machine themselves in order to force them to confront how events in their own lives relate to the mind-bogglingly complex, media-constructed image of our economy,” says Kenyon. “What seems like solid, familiar, everyday currency melts before our eyes, threatening to collapse the entire, fragile system — a visual rendering of our loss of faith in our globally interconnected economy.”