You won’t see these amazing animals on a day at the beach, but they’re there — living in the vast, cold, unexplored midwater region of the ocean. Learn about six of its residents and how they’ve adapted to life in the dark.

A jellyfish that flashes rainbows as it moves. A worm with twisting yellow tentacles that it uses to take in food. A carnivorous fish with its own built-in fishing rod.

Welcome to the ocean’s wondrous twilight zone. In this barely explored region that lies between 650 and 3,000 feet below the surface are creatures beyond your wildest dreams (and, perhaps, nightmares). The sunlight here is barely a glimmer, and the water hovers around a frigid 40°F, or 4°C. “Everything that lives here has amazing adaptations for the challenges of such an extreme environment,” says ocean scientist Heidi Sosik (TED talk: The discoveries awaiting us in the ocean’s twilight zone).

The twilight zone’s inhabitants may serve a critical function for the planet. “The animals travel hundreds of feet to surface waters to feed at night and return to the relative safety of deeper, darker waters during the day,” says Sosik. “They bring carbon in their food into those deep waters, where some of the carbon can stay behind and remain isolated from the atmosphere for hundreds or even thousands of years. In this way, their migration may help keep carbon dioxide out of our atmosphere and limit the effects of global warming.”

But there is so much that researchers still don’t know — which species are migrating? how much carbon are they transporting? what predators and problems do they face? — because the twilight zone is so difficult to study. Oh, and up to one million undiscovered species may potentially live here.

Unfortunately, even as the significance of the twilight zone is being appreciated, it’s under threat from commercial fishing. On August 11, 2018, Sosik and her team at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) began a sweeping exploration of the region. (This work is funded by TED’s Audacious Project.) The team wants to understand how the twilight zone is intertwined with the Earth’s climate, and along the way, they’re likely to find scores of unknown species. Consider the following creatures as a teaser for the discoveries that will be coming soon.

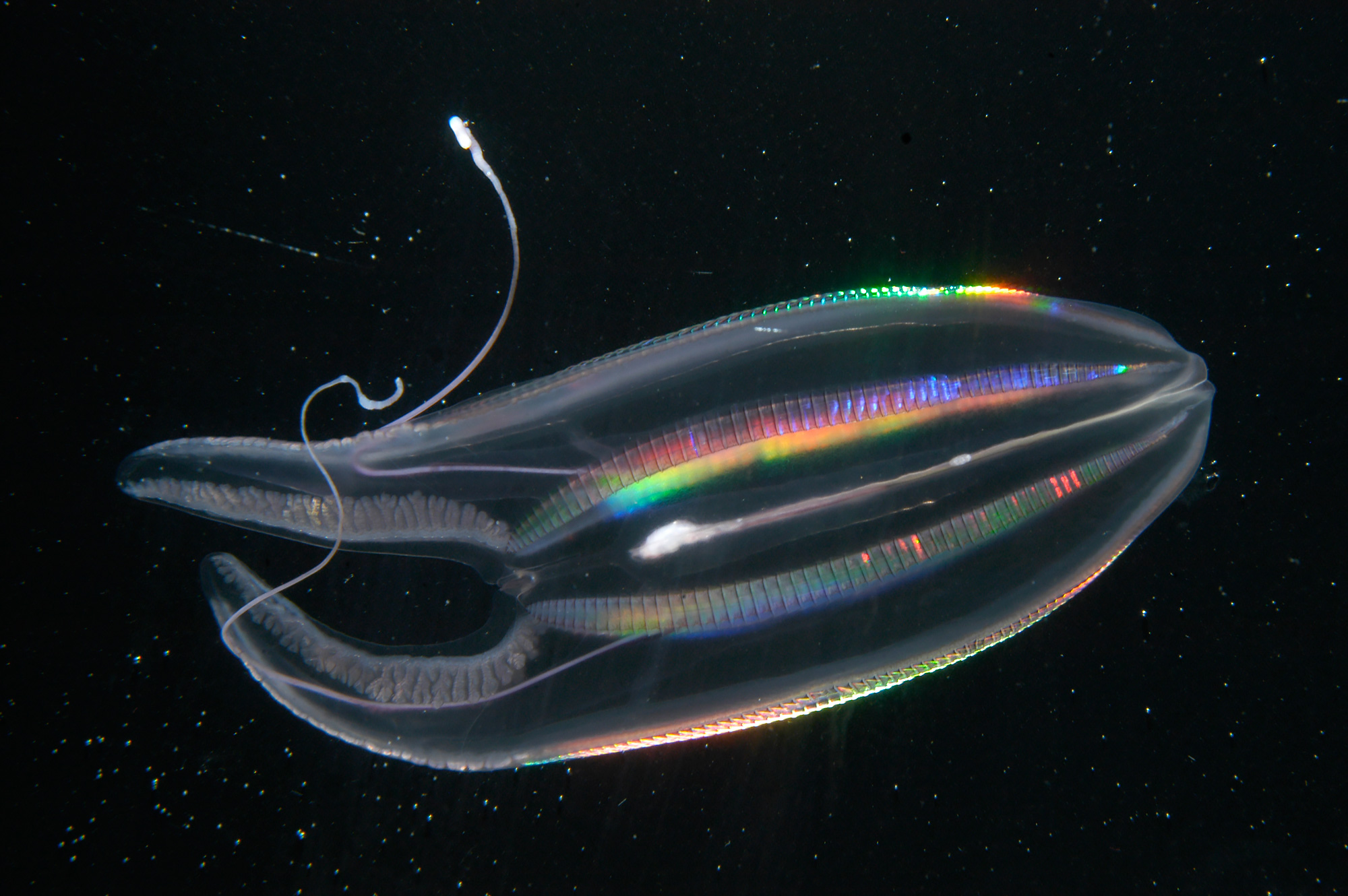

A jellyfish that makes rainbows as it moves

Ctenophores — also known as comb jellies, sea gooseberries, sea walnuts or Venus’s girdles — are found all over the world and come in many different forms. Some are flat; some are rounded; some have lobes; some are shaped like medusa heads. The translucent creatures range widely in size, from a few millimeters to several feet.

But what do they have in common? Eight rows of swiftly beating cilia, minute, hairlike structures that look like tiny combs — and it’s the movement of these cilia that allow the ctenophora to swim. They are the largest group of creatures known to use this type of locomotion. As their cilia wave, something magical happens — they refract light, producing a rainbow-like effect.

However, don’t be fooled by ctenophora’s ethereal appearance — they’re voracious predators. Their diet includes larvae and small crustaceans (like the bioluminescent krill you can see intact in this image), and on a good day, they can consume 10 times their body weight.

A fish with a built-in lure — and a very strange sex life

Anglerfish, which are found worldwide, have grotesque features that seem designed to give humans nightmares. Take those jagged, translucent, incredibly sharp teeth.

Then there’s their size. While most are relatively small, in some species, the females can grow to be three feet in length and weigh up to 110 pounds. They also have a piece of dorsal spine that juts out above their mouths and acts as a built-in fishing rod. A fleshy bit on the end glows (thanks to bioluminescent bacteria living on it) and acts as a lure, attracting crustaceans, fish and other prey. When their next meal is in striking distance, the anglerfish can open its mouth wide enough to devour something twice its size.

But remember, that’s only the female. The males are much smaller and lack the fishing rod protrusion. What’s their survival strategy? They latch onto females with their teeth. Over time, the organisms can fuse together at the blood-vessel level, and the male gives up its internal organs beyond its testes. In some species of anglerfish, one female can host six or more males — for life. Btw, anglerfish can live up to 24 years.

A gelatinous vacuum cleaner for the ocean

Salps are small — ranging in length from about half an inch to 4 inches. With their tube-shaped bodies, they propel themselves through the twilight zone by sucking water in one end and pushing it out the other. As seawater moves through them, salps consume the phytoplankton particles floating in it, receiving a constant infusion of nutrition and energy.

Salps have a lifespan of a few months. They have two alternating generations — one of loners, and the next of aggregates, where individual salps are interlinked in complex chains that move in fascinating ways. When in strong currents or under attack by predators, the salps in these chains will move in a coordinated fashion. But when they’re at ease, each salp moves at its own pace, pulling the chain along with incredible efficiency.

A worm with tentacles that can work like straws

Your average squidworm … isn’t all that average. Discovered in 2007 when WHOI scientists studied the Celebes Sea off the coast of the Philippines, the creature is 4 inches of pure weird. It got its name because when researchers first saw it, they thought it looked a lot like a squid in worm form.

The squidworm has 10 tentacle-like appendages, eight of which comprise its respiratory system. Its two most magnificent look like yellow spirals of Chihuly glass, and they don’t appear to be just for protection or attraction — they may help the worm eat by taking in little particles of marine snow, particles of organic material that float through the twilight zone. The squidworm also has a special way of swimming — the fins along its body flutter, propelling it forward like a set of oars.

One final most interesting fact about the squidworm: scientists think it may be a transitional species. Its biology seems to be a missing link between marine species that lived in the mud of the sea floor and those that inhabit the waters above.

A fish that lights up — to communicate

During World War II, sonar operators noted a strange phenomenon: their measurements showed the seafloor to be 950 meters to 1650 feet below in the daytime — but significantly higher at night. Turns out, they were fooled by the superabundant lanternfish, whose air-filled swim bladders reflected the sound waves.

Lanternfish are tiny — they range in size from almost an inch to nearly a foot — but extremely plentiful. Found worldwide, they may make up 65 percent of the fish biomass in the sea. They can swim in schools as large as high as a two-story house.

More than 250 species of lanternfish have been documented (above is the Lepidophanes guentheri). What unites them are their bioluminescent blue, green and yellow organs, known as “photophores.” Each species’s photophores has its own characteristic pattern. Scientists hypothesize that these photophore patterns may help lanternfish communicate, and potentially pick mates. Some even think this might explain why there are so many different species of the fish. A member of a specific species can recognize the special light-up pattern of others like it. Due to breeding in isolated populations, small variations arise and greater diversification emerges over time.

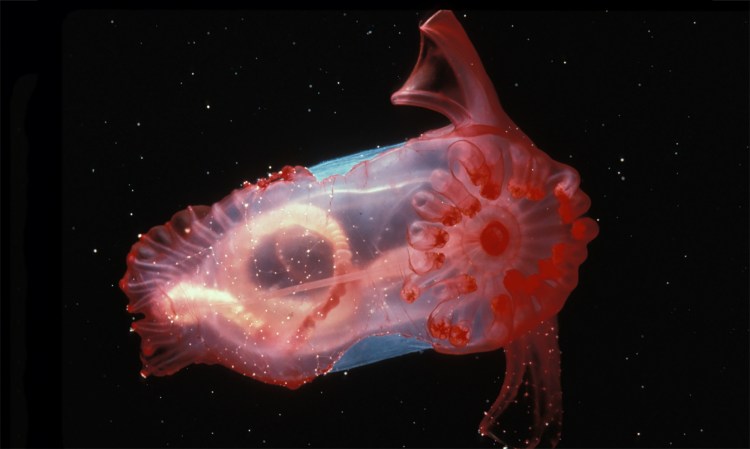

A jellyfish with an alluring light display

This isn’t a tangle of Red Vines — it’s an Atolla jellyfish. Its vivid coloring is actually protective: because most marine creatures see blue light, the creature’s deep red hue makes them practically invisible to their predators.

Atollas are typically one to eight inches in diameter, and they swim between the twilight zone and the deep sea around the world. Tentacles that extend from their ring-shaped core help them move and snare prey, catching food as it floats by. But something incredible happens when prey touches it — the Atolla produces bright, flashing circles of blue bioluminescence.

While scientists don’t know exactly what the Atolla’s light system is saying, they’ve noticed that other aquatic animals find it very intriguing. Marine biologist Edith Widder used its light pattern to create her “e-jelly,” a digital lure used to beckon the ocean’s hidden creatures and nudge them to swim near observation equipment. As she shared in her TED talk, “There’s a language of light in the deep ocean, and we’re just beginning to understand it.” In fact, the e-jelly helped Widder and her team lure in the mythical giant squid and observe it for the first time.

Want to learn more about the twilight zone and what scientists are finding? Become a champion of this Audacious Project idea and find out how you can get involved.