And you thought all that could be done with scissors and a sheet of paper is making snowflakes? Take a look at the spellbindingly intricate tapestries that artist Karen “Bit” Vejle conjures with just her scissors and imagination.

At Easter in Denmark, children commonly make greetings called gækkebrev. Taking a piece of paper, they fold it and cut out a design (often, there’s a poem on the sheet). The sender leaves the letter unsigned, and their recipient has three chances to guess their identity. If they can’t, they owe the sender an egg or a kiss. This was a favorite tradition of Karen “Bit” Vejle (TEDxArendal talk: Papercut poetry) when she was growing up in the town of Brovst, even though her senders were always able to guess her handiwork because her cuts were so intricate.

Historians believe psaligraphy, or the art of papercutting, was practiced as early as the fourth century AD in China. It became popular in Europe in the 16th century, and 19th-century Danish author Hans Christian Andersen was known for making playful paper cuts while he regaled people with stories. Vejle’s first encounter with a contemporary psaligraphist was in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens when she was 16. “I saw a man sitting by a lake, and he was cutting a piece of art from paper. I felt almost like I was hit by lightning,” she recalls. “I watched him for at least half an hour, and then I went home and grabbed my mother’s embroidery scissors. I’ve cut every day ever since.”

Calming body and mind with craft

This depiction of a woman sitting on a box full of “tears and prayers” is a self-portrait. Vejle worked as a TV producer until the early 2000s when she was diagnosed with myalgic encephalopathy (ME), a neurological disorder characterized by chronic pain and exhaustion. “I made this when I was very ill,” says Vejle. “In the middle there is a trapped bird, and it wants to get out and live again. The square below symbolizes how having ME is almost like fighting a battle every day. You need to make a lot of small efforts to get through your day.”

Vejle’s art has been driven in part by her illness. While she’d been cutting since her teens, she turned to it to keep her mind busy when a particularly intense period of fatigue forced her to take a leave of absence from work for several months. When a coworker visited her at home — she was then living in Trondheim, Norway — he was stunned by what he found. “I was sitting and cutting, and he saw my bits and papers spread all over the floor. He grabbed his phone and called the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Trondheim, and said, ‘You have to come see what Bit has.’” After encouragement from the curators, Vejle eventually quit her TV job and began exhibiting her work. She believes the focus required to cut her pieces helps her cope with ME.

Paper premonitions

Vejle says designs often pop up in her head as she’s falling asleep: “Images come to me; this has been my process since I was a kid.” After she wakes up, she rips off a swatch from a specially sourced 10,000-meter paper roll. She doesn’t fold the paper or sketch out her designs first, although she does draw some lines to indicate the general shape of the cut. Then, she just starts. “This is where the magic comes in. If you understand that, you will have a bigger spectrum of ways to manipulate your paper,” she says.

Vejle maintains that papercutting is not a rare gift she’s been endowed with. She believes anyone can do it; it’s all about training yourself, and she attributes her exceptionally steady hands to patience and decades of practice. “It’s a very honest artwork. You cannot cheat because what you have cut out is cut out,” she says. “I have made a lot of mistakes through the years, but it’s like if you give a kid a violin and they practice a lot, there will come a point when they no longer make mistakes.”

The significance of the ballerina bulldog

The “ballerina bulldog” — a dancer accompanied by a dog — is a recurring motif in Vejle’s work. It’s a character she’s made since childhood and one she sees as a symbol of artistic dedication. “A ballet dancer has to work incredibly hard and stay focused for many years to be able to perform,” says Vejle. “It says so much about what we as human beings can achieve.” Like the ballerina, she is methodical — even obsessive — when it comes to her craft. For instance, although she has tried hundreds of pairs of shears, she cuts only with her mother’s embroidery scissors (but worries she’ll eventually break or misplace them). Vejle had the honor of being the first person to wield Hans Christian Andersen’s snippers after his death. “They were enormous,” she says. After she completes a piece, she frequently tucks it under her carpet at home to keep it flat and safe from harm — something she’s done since her teens.

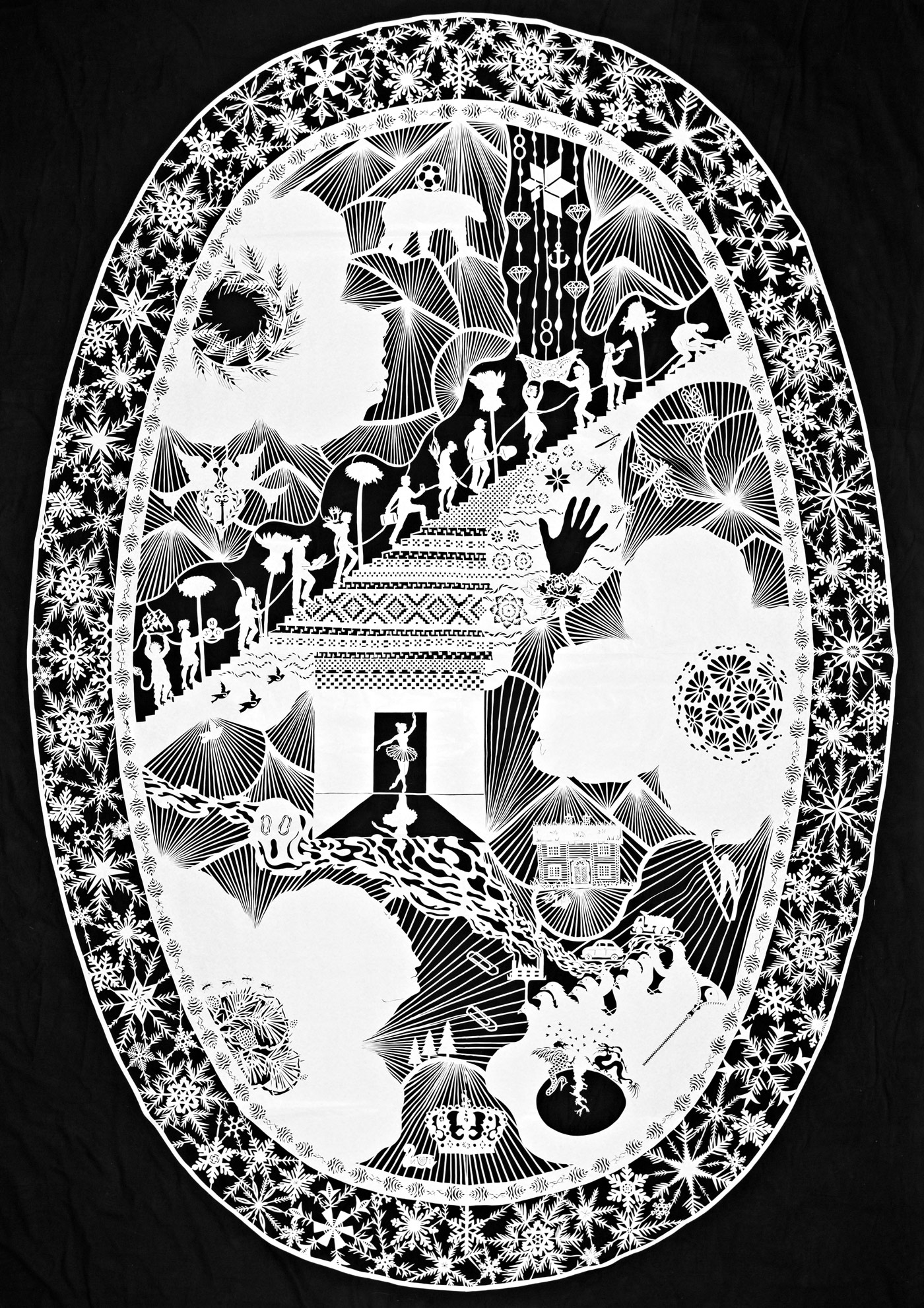

A paper representation of present-day Norway

For Paper Dialogues — a 2014 exhibit created in collaboration with Chinese art professor and psaligrapher Xiaoguang Qiao –Vejle did seven large-scale cuttings of dragon eggs. Dragons are an important symbol of power and strength in both Asian and Scandinavian cultures, and Paper Dialogues celebrated that joint heritage. The two-meter-high eggs took her more than two years to create, and she filled each delicate orb with icons from Norway’s past, present and future. Pictured above is one of Vejle’s eggs depicting the country’s present. “The frame is made of snowflakes. There are patterns of the high mountains, the deep valleys, the Northern lights and the sunsets, which are very intense in Norway,” she says. She snipped silhouettes of flowers to signify a trio of famous Norwegians: artist Edvard Munch, writer Henrik Ibsen and composer Edvard Grieg. Scaling a staircase are 12 Norwegians, each sharing their own story through symbols. “There is a person with a salmon and a mourning mother with a rose on her back, representing the tragic 2011 shooting here,” she says. And, she adds, “there is a troll, because Norway is full of trolls.”

A celebration of religion and folklore

Representing Norway’s past, this egg is framed with a braid of flying dragons. The images are inspired by 12th-century stave churches, distinctive wooden structures that contained Christian and Nordic iconography. Carvings of dragons buttressed their roofs and guarded the entrances to protect parishioners. “This dragon egg tells the story of the christening of the Norwegians. The figure in the middle is from early churches, and she is sitting on a dragon throne,” Vejle says. “She has a key with her and that’s a symbol of power.” The psaligrapher enjoys creating designs that reference her country’s history, fairy tales and natural wonders. “My tradition of using papercuts to tell stories is related to the very first religious images in Scandinavia,” she says. “Before people could read and write, they went to churches to hear God’s word but didn’t understand it because it was in Latin. Stories were painted on the walls, just like cartoons. That’s exactly what I’m doing.”

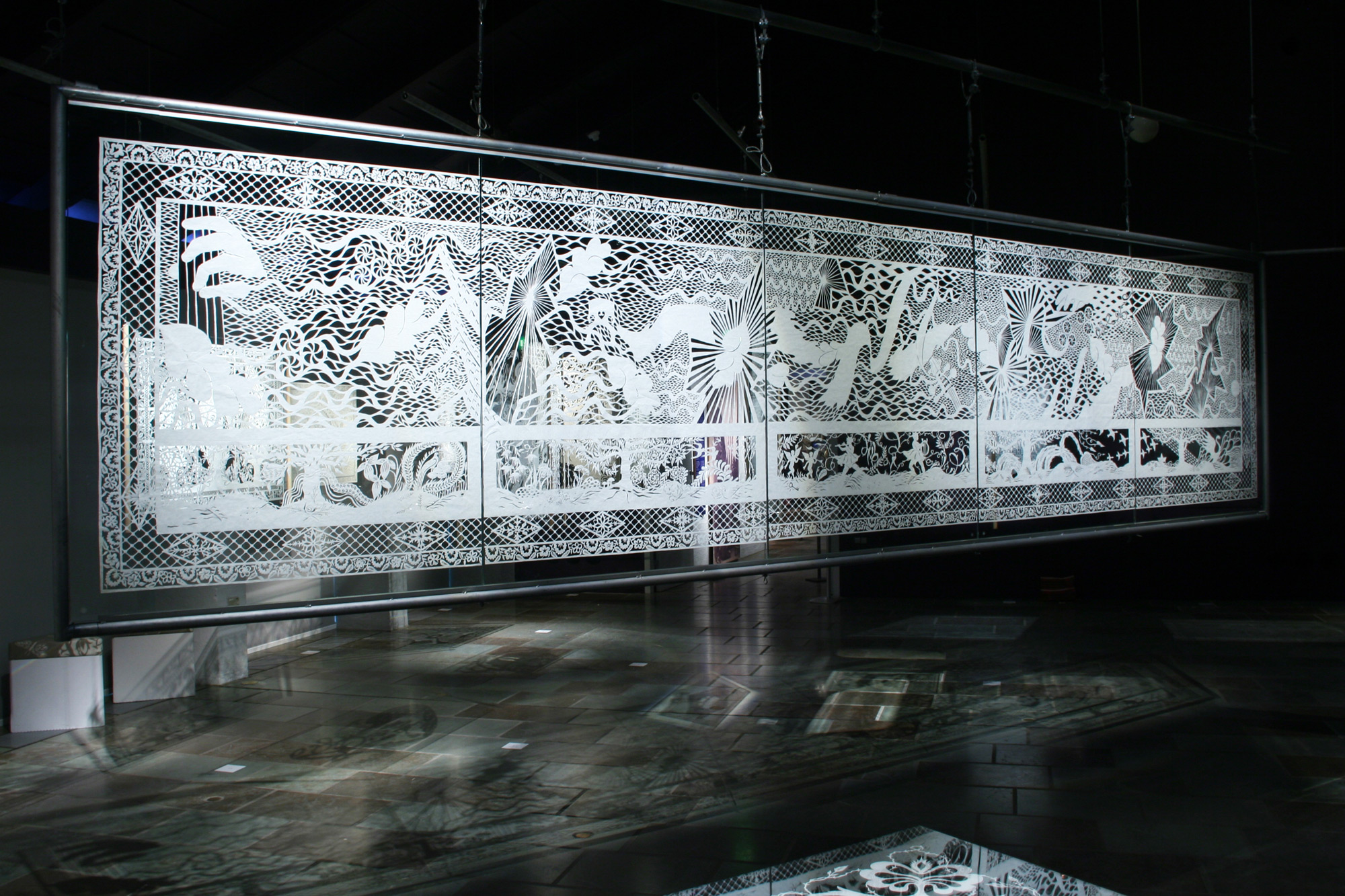

Showing sound through paper

Research for one of Vejle’s papercuts can take several months. To make this piece that was inspired by Dmitri Shoshtakovich’s Opus 8, Vejle listened to the piano piece every day for two months and also read everything she could find about the composer. Only after she’d memorized every note did she feel ready to begin cutting. “It is really easy-peasy, just mathematics,” she says about her process. “You have to form how you’ll cut notes and how a crescendo should look. I built this papercut like a musical work.” She used the cut’s top border to represent sound — how the composition swells, builds and develops — while the bottom border — trimmed with birds and pipers — is figurative. “This particular music piece is rather difficult for people to understand if they’re not into music, so I thought they should have something else to be able to look at,” says Vejle. The five-meter-long papercut took her more than nine months to complete.

Making multiple versions

All-knowing sibyls dot the ceiling of Rome’s Sistine Chapel. She took one of the women and surrounded her with jumping deer — happy objects — as well as shadowy skulls and birds — upsetting ones. For the artist, this piece is about the difficulty of making choices when you’re pulled in many directions. “Everything in life we do requires our choosing things,” says Vejle. “We are responsible for what we choose, but if we’re aware of it, that’s good because then we won’t do very foolish things.” When it comes to choice in her own life, she supports it — she likes having more than one version of a papercut. Since her teens, Vejle has always cut two layers of paper at a time. After she’s finished, she leaves one sheet white and sprays the other black. Vejle likes mounting her work between two panes of glass in order to emphasize its silhouettes.

Inspiring a new generation of paper artists

For “Twittering in the Royal Copenhagen Tree,” a three-meter-tall whopper of a papercut, Vejle filled it with 100 characters, each of which has a different story to tell. Snobbish crows, wise men driving cars, dieting ladybirds, and, natch, a ballerina are anchored by a central tree trunk. “I always tell stories; you’ll find several in each paper cut,” says Vejle. “If you are a child you will see one thing, if you are an adult you will see something else.”

Besides making her own art, teaching and inspiring new psaligraphists are equally important to Vejle, who now lives in the North Sea beach town of Blokhus, Denmark. In March 2018, she and her daughter plan to open a papercut museum in Blokhus. Besides displaying artists’ work, it will host workshops and classes for amateurs and experts alike. A visit to the museum will be a totally unplugged experience, Vejle says. “It lays very deep in our DNA to use our hands. With all the technology that’s around us, we don’t use them anymore. My museum will be a place where there is no technology. You have to meet the paper in person and you will be in direct contact with the material.” And, “it does something good for your soul,” she adds.

All images from Karen “Bit” Vejle.