Architect Diébédo Francis Kéré (TED Talk: How to build with clay … and community) designs with both people and sustainability in mind. Raised in Burkina Faso, though he’s now based in Berlin, Kéré is always keen to include community-oriented spaces that invite people to sit down and engage in thoughtful conversation. The central nature of community is a concept he has borrowed from Burkinabe tradition, and it’s one that plays a fundamental role in his design thinking. His architecture is pragmatic yet quietly playful, driven by a desire to make the most of (sometimes minimal) local resources. So what does he think makes a great community space? One where there’s something for everyone to do what they like, whether that’s sit down, lie back or just be. For that, he focuses on colors, materials and ensuring accessibility for all to empower people to make a space their own. Take a look at some of his designs to see his thinking in building form.

A school for the people, by the people

As a child, Kéré traveled nearly 24 miles to the next village to receive an education — an experience that spurred him to build a school in his home village of Gando, Burkina Faso, while still an architecture student in Europe. The primary school stands as a landmark of community pride, a shared labor of love between Kéré and his village, which ultimately relied on their support, dedication and participation to make Kéré’s vision of easy-access education a reality. “I couldn’t wait to have a degree,” he says of the project, which won him the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004. “I just wanted to use these skills and do something for my community — to create the first school so that the kids can stay by their parents, their relatives, their brothers and sisters and get an education. That was what pushed me.”

The equality of a circle

Circles and round shapes play an integral role in Kéré’s architecture. “A circle is, in our community, something so important. It’s where everyone has the same voice, the same visibility,” he says. “There’s no hierarchy; it’s a space with equality wherever you sit.” This pop-up shop for Camper, in Weil am Rhein, Germany, combines the characteristics of in-store and online shopping for a best-of-both-worlds, multisensory experience that represents the Spanish shoe company through a spectrum of textures, colors, graphics and prints. With its engaging visuals and dynamic acoustics, the space encourages visitors to interact, discover and explore.

Sanctuary from the sun

For this installation at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark, in 2015, Kéré wanted to bring (his version of) a giant tree into the space. Via a uniquely articulated ceiling, he designed the installation to mimic the experience of sharing the space beneath a large canopy of trees. Programmed lights arc and move to give the sensation of streaming sunlight, allowing visitors to escape their intensity on the seats positioned below. In his village, shaded areas become obvious spaces for community gathering. “A shadow,” he says, “can be a luxury in Burkina Faso.”

A village atmosphere in Milan

Influenced by the social and spatial dynamics of an African village, Kéré created this shelter at the Milan Fuorisalone in 2016, using natural materials such as bamboo and stone. The space was created for the design fans thronging the city to meet and relax during the conference. “Where the community gathers is where knowledge is transferred,” says Kéré, who says he sees all of his work as an opportunity to bring people together.

Preserve the past, protect the future

Dating back to the first century AD, the Royal Baths in Meroe are thought to have served two palaces of the African Kingdom of Kush (now Sudan). Kéré’s challenge: to protect and conserve the site as an active archaeological zone, while celebrating its architectural heritage. Mud brick walls and vaulted ceilings provide shelter from the elements, promoting natural ventilation and stabilizing humidity, meaning the excavated artifacts can remain outside for years to come.

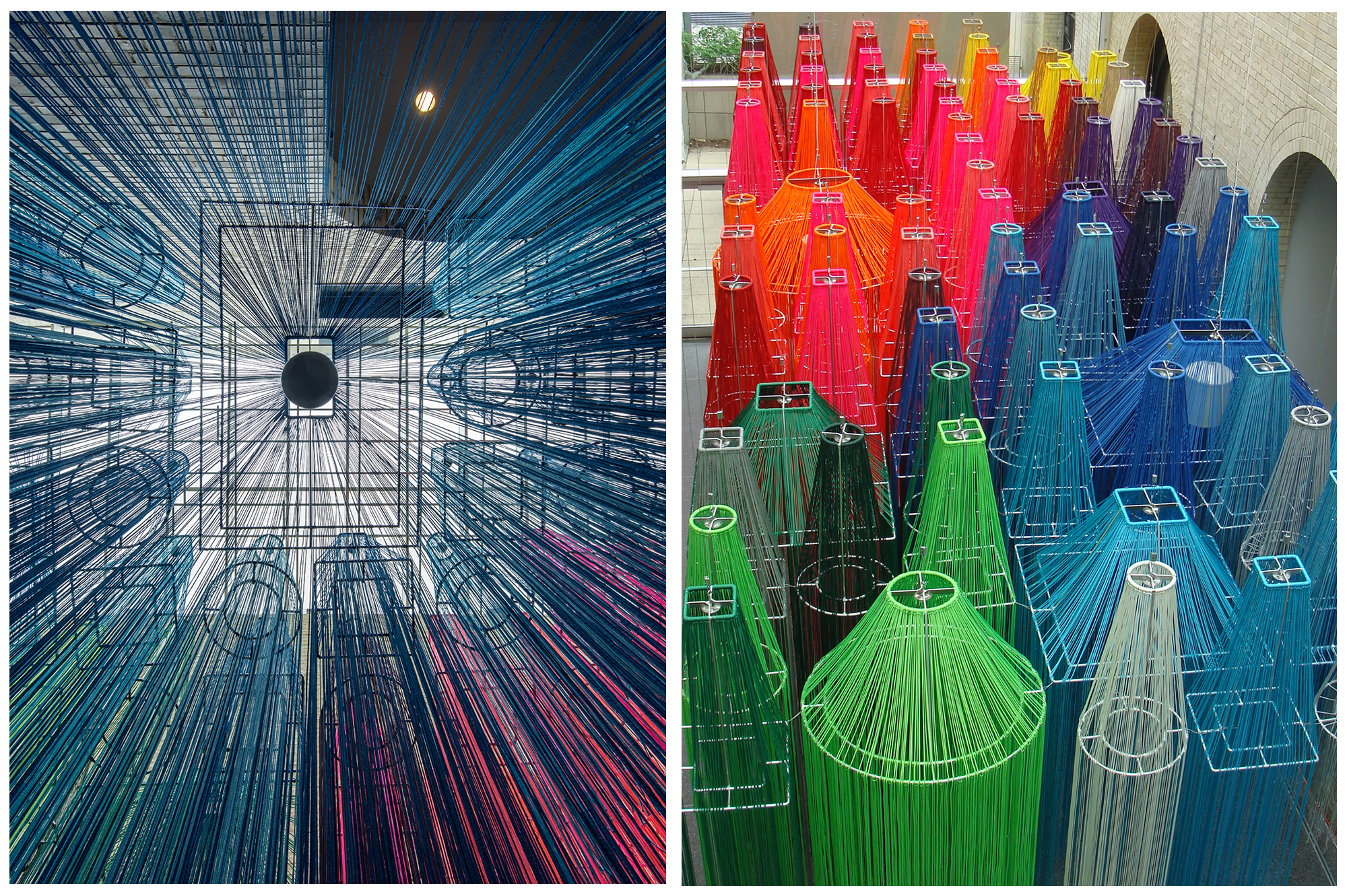

When Gando came to Philly

A retrospective of Kéré’s community-oriented architecture in Burkina Faso was shown at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2016. For one part of the installation, he hung colored cords from the ceiling in a bright, eye-catching display that mimicked the forms of his home. “I wanted to connect Philadelphia with my village,” says Kéré. “The idea was to take the grid of my village, Gando, put it in opposition to the well-designed grid of Philadelphia — and then connect the two with cords.”

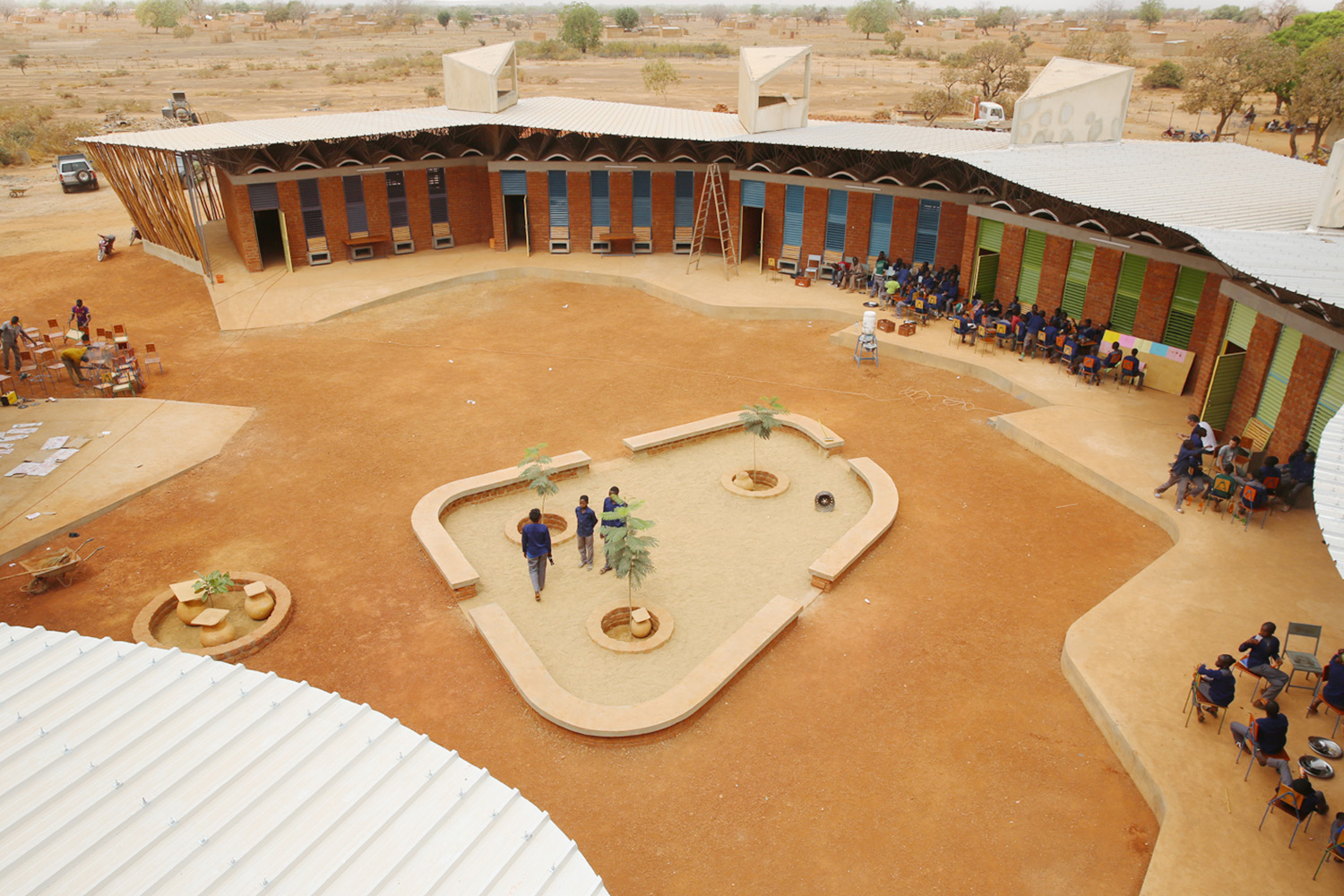

High school + high sustainability

In his latest project, the Schorge Secondary school in Koudougou, Kéré consolidated several of the sustainable techniques used in his earlier designs to explore his own architectural prowess with the available materials within the Burkinabe community. The courtyard design of the school protects the students from the surrounding environment and was modeled after a typical house in Burkina Faso. “The fact that I had the chance to attend education pushed me to try to create a school and to give a better chance to other community kids,” says Kéré. “I wanted to give back to the community the chance that I was given.”

Burkina Faso, a country climbing toward the future

Burkina Faso is a young country born from a difficult past, looking toward a brighter future. Kéré took the 2016 Venice Biennale theme of “Reporting from the Front” to explore how his country could symbolically represent its rebirth after an uprising in 2014. He designed a 12-meter-high, pyramid-like structure to let viewers have a different perspective on life in Burkina Faso. “I was hoping to get people to climb on the top and have another view of the city,” he says. “There are just a few buildings that are higher than three or four stories — in my country, only a few people have ever had the chance to go higher than 12 meters.”

A simple space for a face-to-face

Kéré showcased this simple, engaging design at the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial. It highlights two fundamental themes found throughout his work: the abundant use of locally sourced materials and the desire to put socializing and interaction at center stage. For Kéré, truly sustainable architecture follows one rule: Less is always more. “To use less resources and come out with something that you can call architecture requires a lot of creativity,” he says. “If you can afford every material you want, you don’t care, you just do things, you just build. But if you have material constraints, it forces you to be creative.”

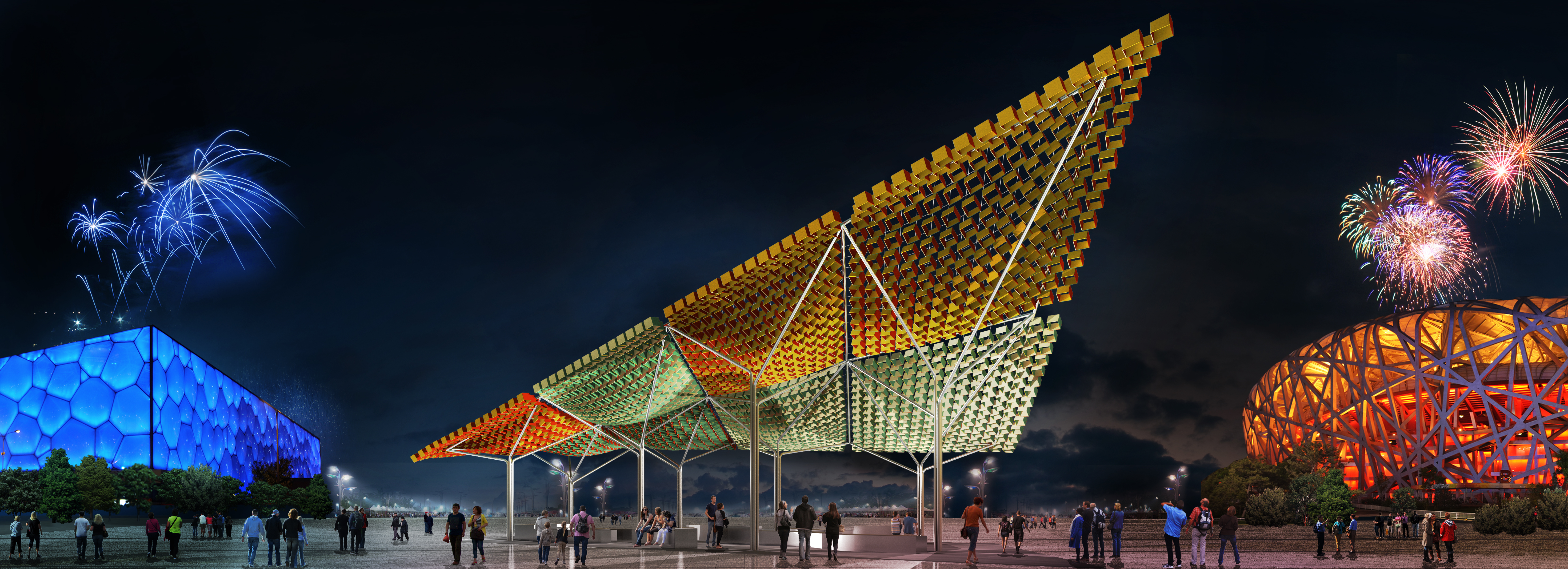

Vibrant vivacity in China

This project was never constructed; it’s a pitch Kéré made to transform one part of the area rebuilt when Beijing hosted the Olympic Games in 2008. His idea: to create a colorful, dynamic pavilion, inspired by a traditional bazaar. “We wanted it to be a cooling place where people could just sit and relax,” he says.