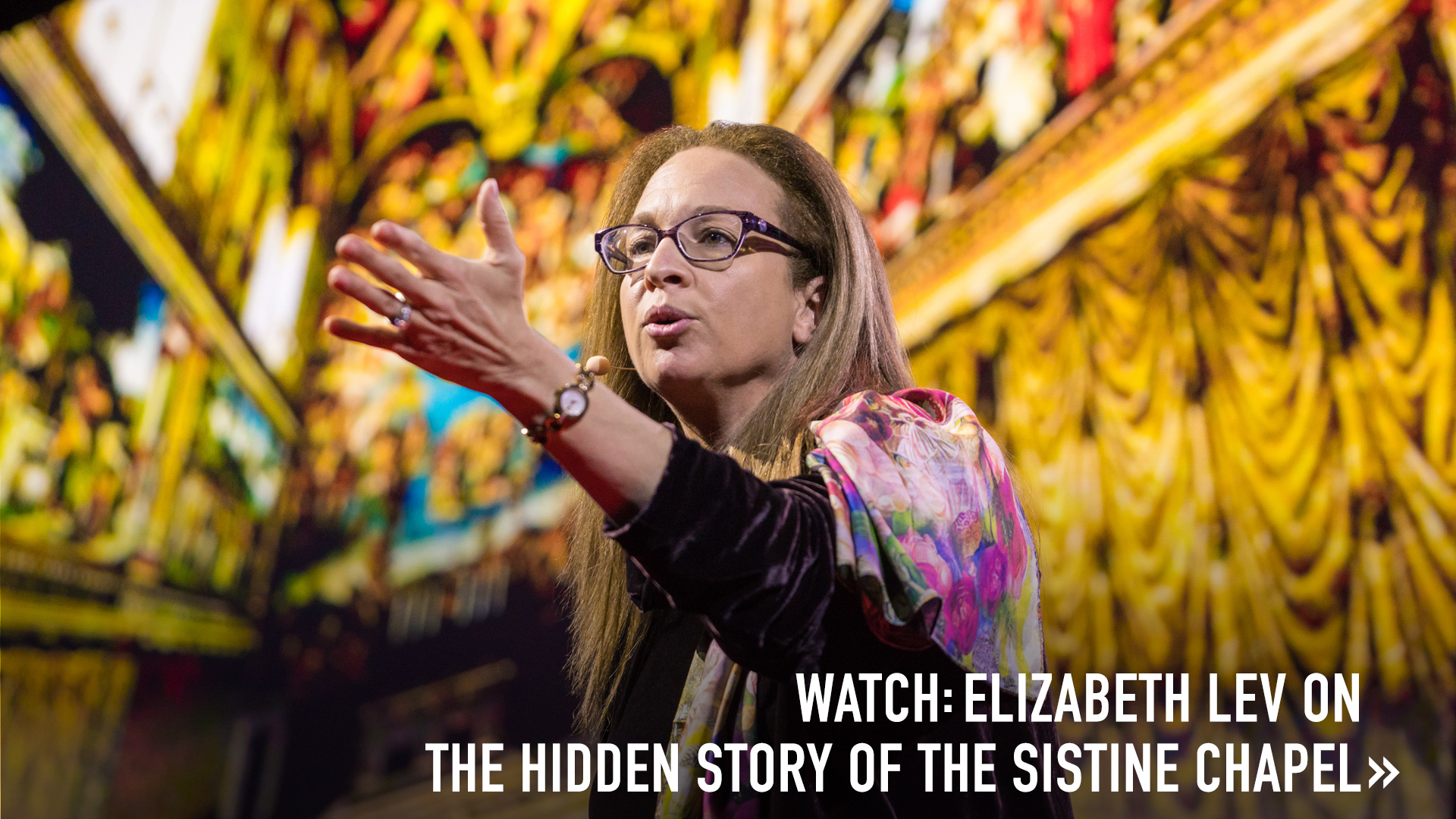

When Michelangelo’s ambitious paintings premiered in the sixteenth century, they touched off a very modern-sounding social media scandal, says art historian Elizabeth Lev.

It was called a “sin,” a “stew of nudes” that could “weaken the faith of others.” In the years following the debut of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings in the mid-1500s, a torrent of complaints about the works’ rampant, joyful nudity rocked the global Catholic Church.

The criticism — from patrons, critics and even popes — may sound like the last gasps of Medieval prudishness, but to Vatican Museums art historian Elizabeth Lev (TED Talk: The unheard story behind the Sistine Chapel), the Sistine Chapel scandal marked a new era of viral opinion-making, powered by Europe’s growing crop of printing presses. And like the latest “hot take” from the TV news, these reactions were often shaped by an echo chamber of critics. The unveiling of the artwork of the Sistine Chapel, Lev says, has all the familiar beats of the modern-day social media scandal.

Radical ideas spread during combustible times. The unveiling took place against the backdrop of the Reformation, when Protestant reformers were lambasting the Vatican as a “den of iniquity.” Within the Papal Court, there was a group of austere clergymen known as the Theatines, who were quite sensitive to Protestant critiques. To them, Michelangelo’s nudes had the makings of a PR disaster. “They just see a wall of naked bodies,” Lev says. They were countered by avant-garde clergymen, such as cardinals Cunaro and Medici, who hailed the painting as the height of religious art. “So it’s like two different PR strategies,” Lev says. “One says: ‘We need the more austere, modest outlook,’ and the other one says, ‘No! We’ve got to make things look great and fun and beautiful and heroic. We’ve got to get people psyched.’” It was a debate too inflammatory to contain within the confines of the Vatican, Lev says. “What happened next is of course the reaction exploded, because the printing press allowed many people to see it instead of only a few.”

One artful critic can inflame a continent. “The guy who really gets all of this started,” says Lev, “he’s quite the troublemaker, is a man named Pietro Aretino. He’s got a great turn of phrase, he’s funny.” Aretino could also be downright ferocious in his critique of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment wall fresco, writing that it “makes such a genuine spectacle out of both the lack of decorum in the martyrs and the virgins, and the gesture of the man grabbed by his genitals, that even in a brothel, these eyes would shut so as not to see it. It would be less of a sin for you not to believe than by believing in this manner, to weaken the faith of others.” Incidentally, Aretino had his own kinks, Lev says. “Aretino is a famous, and I mean famous, writer of pornography.”

Michelangelo was not painting for the public. Indeed, there was no public entrance to the Sistine Chapel. Access was restricted to the crème de la crème of the Papal Court. When Michelangelo unveiled The Last Judgment, in 1541, his audience numbered little more than 500 clergy. Their reactions ranged from ecstatic to appalled. “The work is of such beauty,” wrote one eyewitness, an agent to the Cardinal Gonzaga of Mantua, “that Your Excellency can imagine that there is no lack of those who condemn it.” It was an understatement.

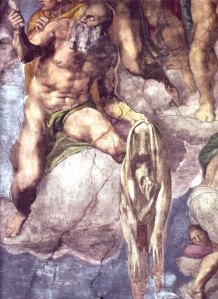

Artists defy the norms at their own risk. “Michelangelo’s shocker was to take the saints and the martyrs and remove their clothes,” Lev says. A nude saint here and there was not unheard of in the annals of art history, particularly for saints who disrobed in an act of penitence. But the figures in Michelangelo’s painting looked anything but ashamed. “These figures revel in their bodies,” Lev says. “They hug and they embrace and they flex and they pose. They’re not going, ‘Oh my goodness, it’s so uncomfortable, all these muscles.’ They love their bodies, you can tell.” Compared with traditional depictions of The Last Judgment, where nude mortals were quaking before their fully clothed superiors, Michelangelo exposed flesh where viewers least expected it. “So that’s a very, very, strange image,” Lev says.

Amid the storm of censoriousness, opportunists strike. Aretino’s early critique prompted an outpouring of criticism from Michelangelo’s fellow artists, who see an opportunity to build their own careers. “So the snowball starts with a guy who’s very, very angry. He gets a friend of his to write what garbage this is, and then his friend to start writing, and then the next thing you know, you have a whole bunch of other people who who were sort of joining in and trying to make their reputations by damaging Michelangelo’s,” Lev says. “Which is a very human and normal thing that people do.”

A sly response to all would-be censors. It seems Michelangelo weathered the scandal in silence. At least there’s no record of his response in the printed materials from that period, though he did use his painting to take a subtle strike at one of his critics, the papal courtier Biagio da Cesena. “We see Michelangelo lose his temper for a second and paint in the guy at Minos the judge of Hell.” The demon is depicted with its tail wrapped twice around Cesena. “So if you have the tail wrapped around your waist twice, it means you’re going to Hell for being lustful, and doesn’t that suggest to you that what Michelangelo was proposing is that if you look at this painting and all you can see are naked bodies, and all you can see is pornography, the problem is you, not me?”