You may think glaringly offensive items have nothing to do with you or your closet. “I would never buy an offensive item or appropriate something from another culture,” you might say. “That’ll never be me.”

But it helps to be sure.

I’ve seen blond Caucasian women wearing henna hand tattoos or cornrows with dashikis (traditional African caftans), and American tourists posting selfies while wearing turbans with embroidered caftans in the Middle East. I can’t help but wonder if they see these things as colorful, disposable accessories that can be amusingly donned and then ditched.

In general, I don’t believe those people are malicious or intend to hurt anyone when they borrow the symbols of a culture that isn’t their own. But when you wear another group’s cultural signifiers head to toe, it can create the impression that you see them as a costume. It’s demeaning.

Being white and wearing a dashiki might be interpreted as problematic; wearing one with cornrows or dreadlocks in your hair almost certainly would be.

We have a term within the Black community: “Christopher Columbus-ing.” It’s taking something from a marginalized group and renaming it to claim it as your own. Or, as the Washington Post’s Clinton Yates explained, it’s “showing up someplace and acting as if history started the moment you arrived.”

When Kim Kardashian wore cornrows or Fulani braids — a hairstyle with deep roots in the Black community — but called them “Bo Derek braids” (a reference to the blond-and-blue-eyed movie star who wore them in the 1979 movie 10), she was met with outrage. Black people I know were like, “No, these are cornrows or boxer braids! We grew up with this! These are styles we get as kids!”

Kardashian more recently wore traditional Indian bridal forehead jewelry to a Sunday church service, prompting one Instagram commenter to remark, “I love how this is from the Indian culture and no recognition [is] given whatso[e]ver.”

Remember Miley Cyrus’s 2013 makeover from Hannah Montana to twerking, grill-flashing, hand signal-throwing, bandana-wearing, tongue-thrusting Bangerz hitmaker? As Dodai Stewart wrote at the time for Jezebel, Cyrus “can play at blackness without being burdened by the reality of it … But blackness is not a piece of jewelry you can slip on when you want a confidence booster or a cool look.”

If you don’t understand cultural appropriation, imagine working on a project and getting an F and then somebody copies you and gets an A and credit for your work.

Privilege and erasure are at the heart of any discussion about appropriation. It’s not that Kim K or Miley Cyrus meant to offend with their hairstyles or jewelry. Their intent may very well have been homage.

But as non-Black and -brown celebrities, they have the privilege to wear the looks associated with another person’s culture when that person can’t necessarily wear looks from her own culture without suffering some type of fallout. Sometimes I wish I could wear those “Bo Derek” cornrow braids because I just want my hair off my face.

But what does it signal when I wear them as a Black woman? It denotes that I’m ghetto or that I’m likely not educated. Maybe I’m into rappers and I smoke weed. I don’t have the license to wear this particular hairstyle as I want to. Kim Kardashian, however, can wear it any day of the week and walk into an office or a business meeting, and no one is going to think she uses drugs or lacks sophistication. No one is going to fire her or Miley, or kick them out of school for wearing these hairstyles.

I read a quote on Instagram (posted by New York City hairstylist Tenisha F. Sweet) that said, “If you don’t understand cultural appropriation, imagine working on a project and getting an F and then somebody copies you and gets an A and credit for your work.”

Sarah Jessica Parker wears a turban in Abu Dhabi in Sex and the City 2 — and it’s fashion. But a Middle Eastern or Indian or other minority woman wearing the same turban in the US has to worry if someone is going to think she’s a terrorist or a palm reader or whatever other stereotypes are associated with wearing a turban.

In America, turbans are often associated with danger. Comprehensive research out of Stanford shows we exhibit automatic biases — heightened since 9/11 — against those wearing turbans, are more prone to perceive innocent objects held by the turban wearer as weapons, and, in video games at least, shoot at them more frequently simply because they wear turbans. But no one is going to worry that Sarah Jessica Parker might blow up the plane. She actually has the privilege to enter most rooms and spaces dressed any way she likes without people attaching stereotypes to her.

I know a Middle Eastern young woman who wears a head covering for religious reasons. When she goes out, she thinks twice: “Maybe I should show a bit of my hair or wear more makeup so I seem less threatening?” These are the second thoughts that some people have to consider when they’re trying to display their own culture. Others only have to think once.

Privilege isn’t about what you’ve gone through; it’s about what you haven’t had to go through.

Privilege is a touchy subject, because it puts the people who have it on the defensive. (And that’s pretty much all of us, since we all benefit from one form of privilege or another.) As activist Janaya “Future” Khan so powerfully explained in a viral video, people have explosive reactions to the word “privilege.” They feel defensive because they themselves have almost certainly been marginalized in some way; they too have gone through heartache and trauma at the hands of others.

But, as Khan clarifies, “Privilege isn’t about what you’ve gone through; it’s about what you haven’t had to go through.”

This much I know: In order to work through these issues, we have to hear one another, to see one another’s humanity, to acknowledge one another’s hurt. We need understanding at every level. As Roxane Gay writes in her book Bad Feminist, “We should be able to say, ‘This is my truth,’ and have that truth stand without a hundred clamoring voices shouting, giving the impression that multiple truths cannot coexist.”

On the fashion front, what is someone who loves lots of different cultures to do? Are we as individuals “allowed” to wear only the native styles of our ancestors? Should everybody just shop at the Gap and call it a day? I’m not discouraging anyone from being inspired by other cultures, and I don’t think we should water down our looks for fear of the thought police.

It comes down to the spirit in which you wear a garment — and whether that spirit communicates respect versus condescension.

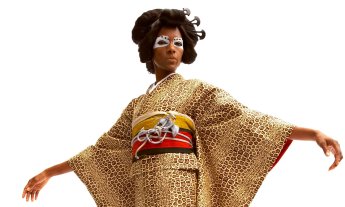

There are super-simple ways to be sensitive without sacrificing style. Personally, I love wearing kimonos. I recently gave a lecture on their history at the Newark Museum. I was fascinated to learn how the garment has evolved over millennia, and how even today in Japan, there are strict rules about how a kimono has to be tied and folded. When I wore a kimono for that lecture, I made it my own. I paired it with black over-the-knee suede boots and minimal accessories. In other words, I didn’t wear wooden clogs or style my hair in a shimada, the way that Vogue editors styled a white model for a famously appropriative and incendiary 2017 spread. Again, it’s culture, not costume.

But the line differentiating the two isn’t always clear. Reaction was mixed when a Caucasian high school student wore a cheongsam to her senior prom. It’s important to note that her hair, makeup and accessories were tasteful and subdued. One angry observer tweeted: “My culture is NOT … your goddamn prom dress.” But the popular opinion in China, per some press reports, was to celebrate the teen for her stylish choice.

There is no law on whether or not it’s acceptable to wear a cheongsam if you are not Chinese. It comes down to the spirit in which you wear a garment — and whether that spirit communicates respect versus condescension.

The line between celebration and appropriation gets crossed when there is the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices or ideas of one group by another, typically more dominant group. It comes down to whether you’re aware of a look’s cultural history, whether you give credit where it is due (as opposed to renaming the style), and how you honor whatever you are borrowing.

So borrow away — just be conscious about it.

The next time you’re thinking about wearing an item from another culture, here are some tips for what to do:

Are you Halloween-ing it?

When you wear cultural items head to toe, it can seem like a Halloween costume. Mix in other elements as well.

Educate yourself

Do a little research into a garment’s cultural history before you wear it. I’m not saying pull out a book and read a whole history of boxer braids or the kimono. But google it. Do your due diligence by looking into a style’s historical meaning, so you’re not walking around inadvertently renaming or disrespecting something.

Be respectful

If you are wearing a spiritually significant item from a culture other than your own, don’t behave in a way that’s antithetical to that culture’s values and customs. Of course, we are all free to do as we wish — as my friends might say, “Who’s gonna check me, boo?” But I personally wouldn’t wear a hijab to a bar or a bindi with a bikini. I would be careful not to dishonor the symbol.

Ponder your privilege

Think about whether someone else would encounter bias if she wore the style you’re considering. If a member of the culture that originated the look were to wear it, might she suffer for it? If the answer gives you pause, rethink whether your fashion statement is worth it.

Excerpted from the new book Dress Your Best Life: How to Use Fashion Psychology to Take Your Look and Life to the Next Level by Dawnn Karen. Reprinted with permission from Little, Brown Spark, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2020 by Dawnn Karen Mahulawde.

Watch her TEDxFIT talk here: