Shakespeare coined new words when he needed — or merely wanted — them. Can you guess which words were invented by the Bard?

English heading into the sixteenth century was a makeshift, cobbled-together thing. No fewer than eight conquering peoples had added to our vocabulary and shaped our syntax. But the Brits were doing more than just borrowing, swiping and outright stealing words from other languages. Versifiers like Chaucer let newfangled words from the street amble onto the literary stage – newfangled and amble being two of them.

By the time Elizabethan dramatists sought expression for ever-more sophisticated sentiments, crowds cheered their linguistic daring.

A short list of verbs invented by the Bard:

arouse

besmirch

bet

drug

dwindle

hoodwink

hurry

puke

rant

swagger

Shakespeare also minted new metaphors, many now clichés, but fresh in his time:

it’s Greek to me

played fast and loose

slept not one wink

seen better days

knit your brows

But you didn’t have to be a Shakespeare to play word god. Everyday speakers in the Renaissance formed new words like crazy, often by adding prefixes and suffixes. Most of the words formed this way were nouns and adjectives:

Add –ness to bawdy and you get bawdiness!

Do the same to brisk and you get briskness!

Hitch –er to the end of a verb and you get everything from a feeler to a murmurmer.

New verbs could be had for the cheap price of a suffix, like:

–ize (agonize, apologize, civilize)

–en (blacken and whiten, loosen and tighten, madden and sadden)

Then there were prefixes like the wanton un-, which paired up with nouns, adjectives, participles, verbs, and adverbs, such as:

uncivility

unclimbable

unavailing

unclasp

uncircumspectly

Then, in the midst of this linguistic riot, King James I commissioned the Bible’s translation into English in 1604. England had just broken away from the Roman Catholic Church, so our bastard tongue became – boom! – a bastion of national identity.

Between Shakespeare and King James, English gained clout, but it lacked clarity.

“Our language is in a manner barbarous,” said the poet and critic John Dyrden in 1693.

“Our language is in a manner barbarous,” said the poet and critic John Dyrden in 1693. Other men of letters (and they were all men) fretted that English was unbridled, wild. Meanwhile, the printing press was spreading the Word—or rather the tens of thousands of them. English was changing so fast, some poets feared their works wouldn’t be understood by future generations.

“Our Language is extremely imperfect,” Jonathan Swift, writer and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, complained to the Earl of Oxford in 1712. “Its daily Improvements are by no means in proportion to its daily Corruptions; and the Pretenders to polish and refine it, have chiefly multiplied Abuses and Absurdities.” And that wasn’t all, Swift added: “In many Instances, it offends against every Part of Grammar.”

Certain clerks and clerics in the eighteenth century longed for a less rustic language and took it upon themselves to craft a “Queen’s English.” They invented rules for our unruly tongue. The problem was, they stole the rules from Latin.

Nevertheless, these rules have been sanctified in books and repeated by people who ignored the history of English. They have been passed down by generations of schoolmarms (and schoolmasters).

This is the muddle we find ourselves in today.

Yet we all yearn to write well. We dream of moving people with our words. It all starts with the verb, the word linguist Steven Pinker calls “the little despot” of every sentence.

This excerpt is adapted with permission from Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch: Let Verbs Power Your Writing by Constance Hale (W.W. Norton & Company).

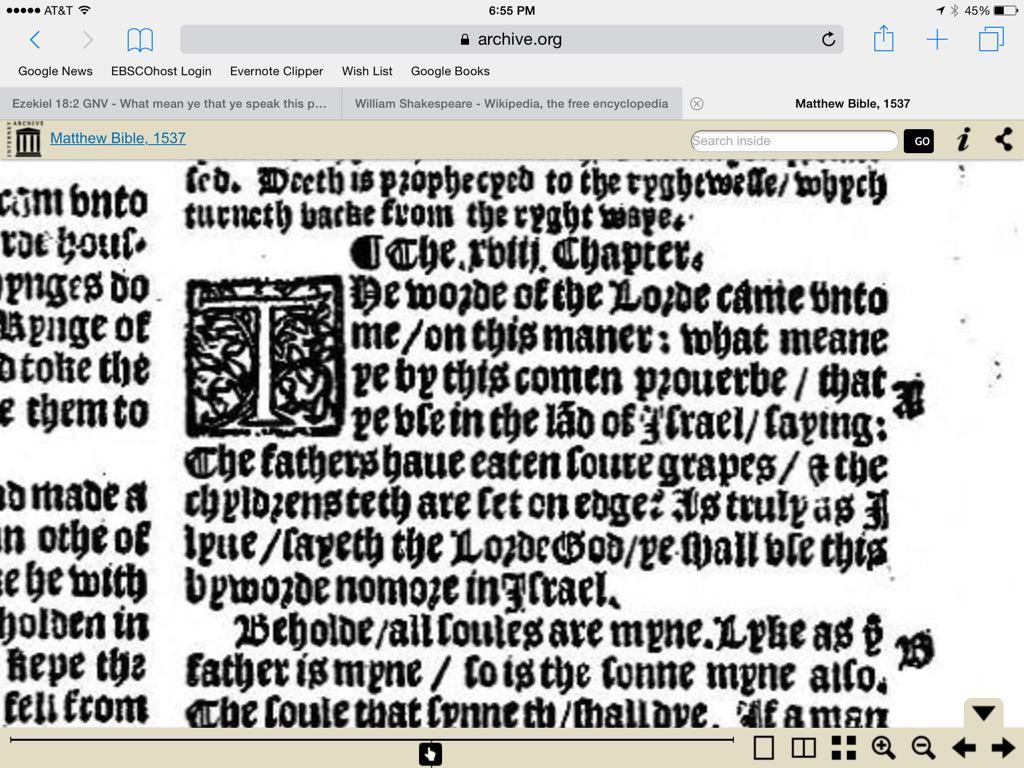

Note: An earlier version of this piece suggested that Shakespeare coined the metaphor “have your teeth set on edge,” but via Twitter, readers @FrJody and @Brent_Pollard note that this phrase appears in the Matthew Bible of 1537, and can be found in Jeremiah 31:29-30 and Ezekiel 18:2. @FrJody shares this screengrab: