This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from people in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

When you think about eating better, what comes to mind? Adding servings of fruits and vegetables to your lunches and dinners? Cutting down on processed foods? Consuming more locally grown produce?

Chronobiologist Emily Manoogian has found that adjusting one specific factor — when we eat — could improve our lives just as much as changing what we eat. She says, “Much the same way that you should eat a healthy meal every day, you should also eat it when your body expects it.”

Our bodies run on a 24-hour clock — right down to our cells. “Pretty much anything that you would get tested at the doctor’s office has a circadian rhythm. For instance, your heart rate and blood pressure naturally rise in the afternoon and are lowest while you sleep,” says Manoogian, a researcher at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. This rhythm “helps us be alert when we wake up, it has our digestive system ready to process food when we eat, and it helps our organs rest and repair while we sleep.” In her research, Manoogian monitors the timing of daily habits in thousands of people around the world to gain insight on how these affect their health.

In our busy and highly stimulating world, our circadian rhythm could use some assistance. “The two biggest cues you can give your body to tell it the time of day [are] light and food,” says Manoogian. “Evolutionarily, those were very reliable cues to know the time of day. But in modern society, light and food are available around the clock. This can lead to circadian disruption.”

Such disruption is associated with an increased risk of heart disease and diabetes. The World Health Organization has listed it as a probable carcinogen when it becomes a regular feature of life due to shiftwork patterns. Even our treasured weekends and holidays can throw off our body’s schedule in a phenomenon known as “social jetlag,” simulating the feeling of having crossed several time zones as result of staying up or sleeping later, or eating and drinking at odd hours.

“You need to keep your body on its schedule so it can prepare itself for what it needs to do,” says Manoogian. “This means using those external cues to support your biological clock: tell it when it’s morning and when it should be awake, and decrease simulation at night so it can get a proper rest.”

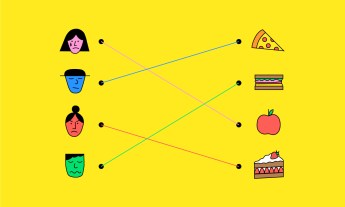

One way to help our bodies is by practicing “time-restricted eating.” What that means is this: Eat within the same 10-hour window every day. That’s it. So if the first thing that you consume is at 8 AM, your last meal should be at 6 PM.

The end of your 10-hour eating window should not coincide with your bedtime. (Water is fine, however.) “Leave at least three hours before you go to bed … so your body can get that proper rest,” says Manoogian. “[Your body] needs at least 12 hours of fasting every day to function properly.”

If you decide to try time-restricted eating, this does not mean you can never go to a party again or have a midnight snack. When you do exceed your 10-hour window, just get on track the next day. But you may find the benefits of this practice outweigh the inconvenience. “Time-restricted eating … can improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, can lead to about a 5 percent weight loss, improves endurance and decreases blood pressure,” says Manoogian.

If you’re interested in participating in Manoogian’s research and in tracking your own rhythms, check out the free tracking app MyCircadianClock (which was co-created by Manoogian).

Watch her TEDxSanDiegoSalon talk here: