We see the familiar symbol everywhere — in text messages, signs, cakes, clothing, and more. But we also know the real heart looks nothing like it. Historian Marilyn Yalom tells us how the anatomical organ became the symbol that we all know today.

In 2011, I went to the British Museum in London to see a collection of 15th-century artifacts, which included gold coins and jewelry that were part of the Fishpool Hoard found in England in 1966. I was particularly attracted to a heart-shaped brooch (below, one of the heart brooches from the hoard).

That day, I noticed the heart’s two upper lobes and its V-shaped bottom point as if I were seeing them for the first time. It quickly dawned on me that the symmetrical shape is a far cry from the ungainly lumpish organ inside us. From that moment on, the figure of the heart pursued me. I wanted to answer two questions: “How did the human heart become transformed into the iconic form we know today?” and “How long has the heart been associated with love?”

As far back as the ancient Greeks, lyric poetry identified the heart with love in verbal conceits. Among the earliest known Greek examples, the poet Sappho agonized over her own “mad heart” quaking with love. She lived during the 7th century BC on the island of Lesbos surrounded by female disciples for whom she wrote passionate poems, now known only in fragments, like the following: Love shook my heart, Like the wind on the mountain Troubling the oak-trees.

Greek philosophers agreed, more or less, that the heart was linked to our strongest emotions, including love. Plato argued for the dominant role of the chest in love and in negative emotions of fear, anger, rage and pain. Aristotle expanded the role of the heart even further, granting it supremacy in all human processes.

Among the ancient Romans, the association between the heart and love was commonplace. Venus, the goddess of love, was credited — or blamed — for setting hearts on fire with the aid of her son Cupid, whose darts aimed at the human heart were always overpowering.

In the ancient Roman city of Cyrene — near what is now Shahhat, Libya — the coin (above) was discovered. Dating back to 510-490 BC, it’s the oldest-known image of the heart shape. However, it’s what I call the non-heart heart, because it is stamped with the outline of the seed from the silphium plant, a now-extinct species of giant fennel. Why in the world would anyone have put that on a coin? Silphium was known for its contraceptive properties, and the ancient Libyans got rich from exporting it throughout the known world. They chose to honor it by putting it on a coin.

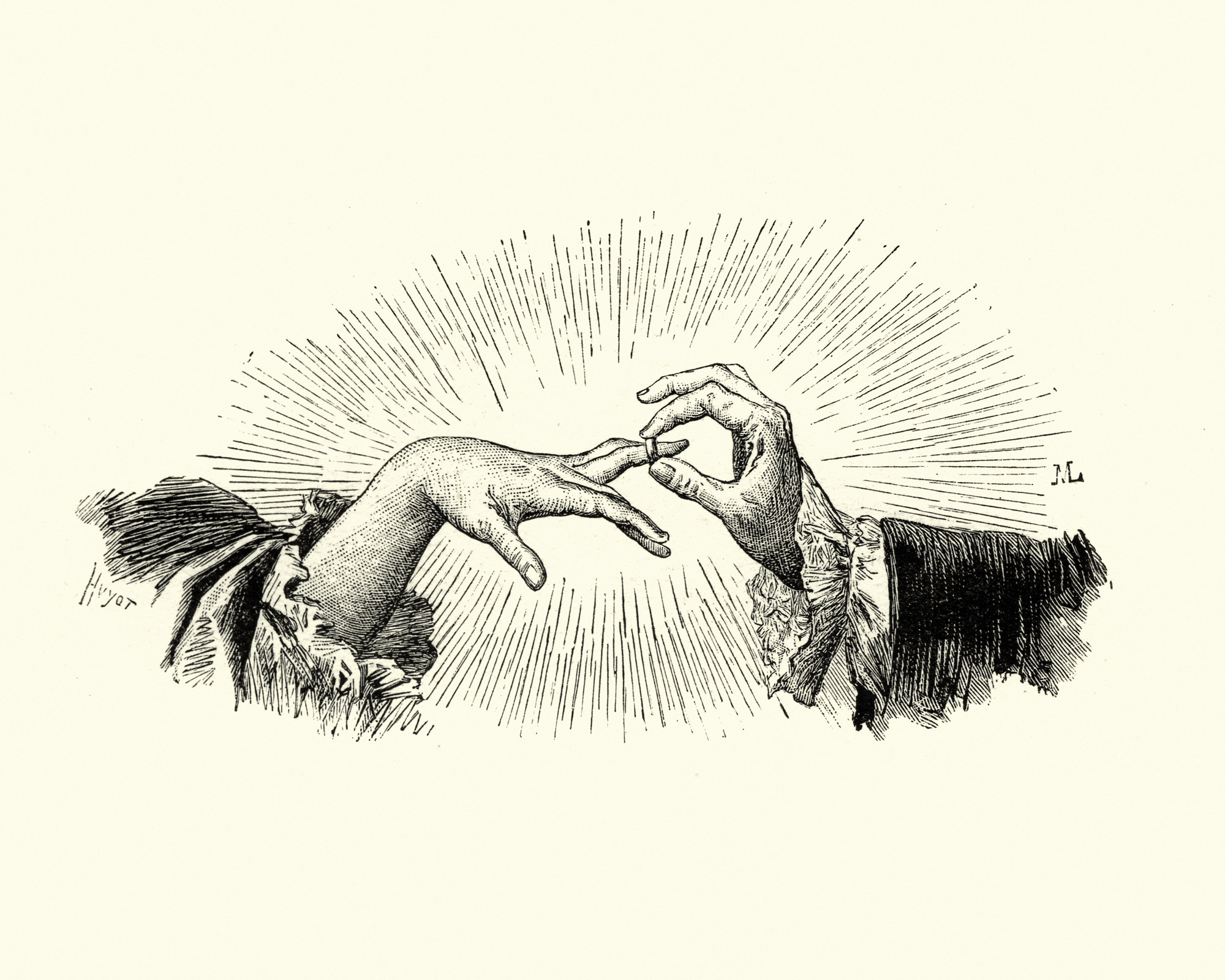

The ancient Romans held a curious belief about the heart — that there was a vein extending from the fourth finger of the left hand directly to the heart. They called it the vena amoris. Even though this idea was based upon incorrect knowledge of the human anatomy, it persisted. In the medieval period in Salisbury, England, during the church ceremony in the liturgy, the groom was told to place a ring on the bride’s fourth finger because of that vein. Wearing a wedding ring on that finger goes back all the way to the Romans.

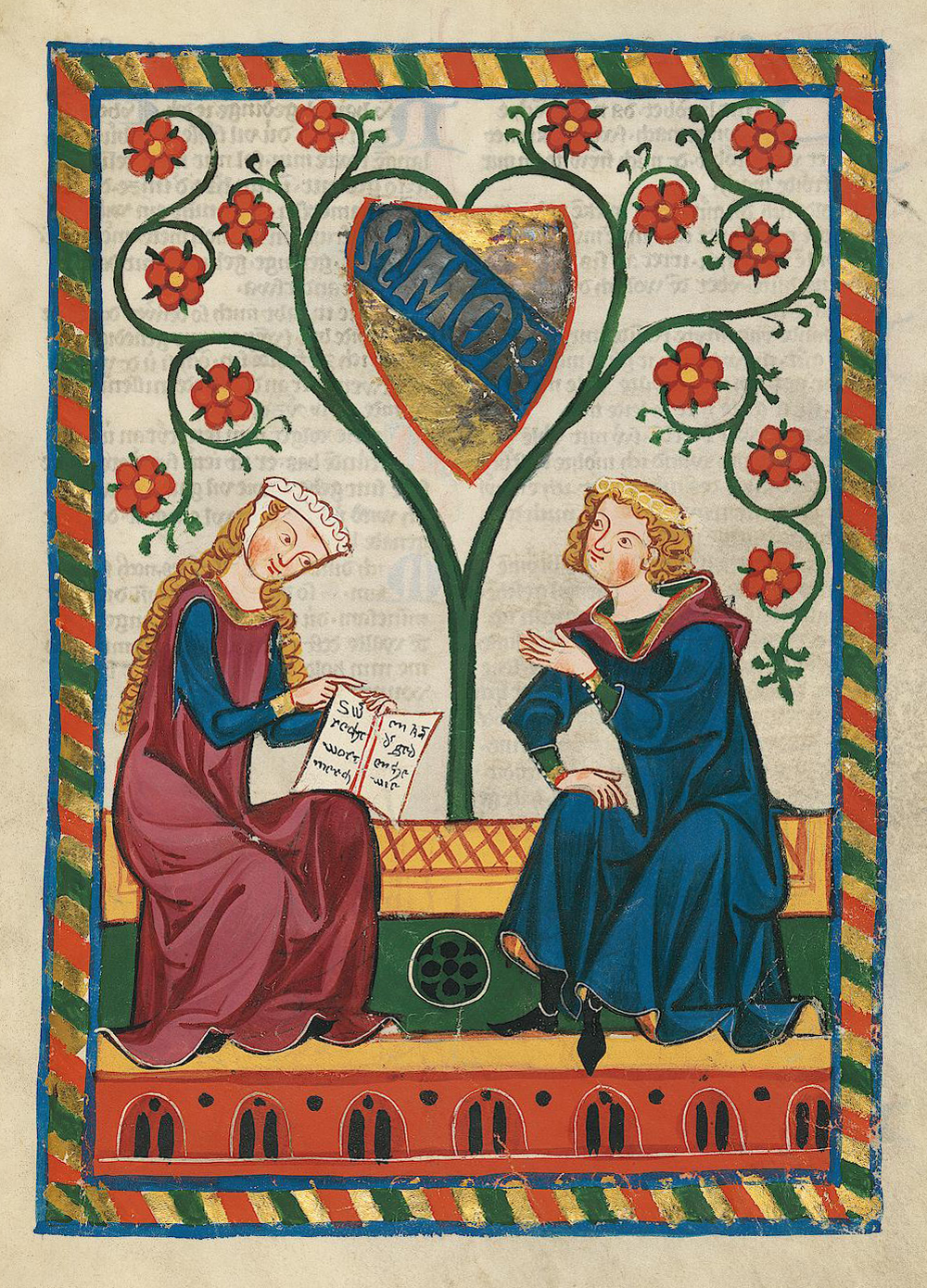

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the heart found a home in the feudal courts of Europe. Minstrels in France celebrated a form of love that came to be known as “fin’ amor.” Fin’ amor is impossible to translate: today we call it courtly love, but its original meaning was closer to “extreme love,” “refined love” or “perfect love.” Courtly love required the troubadour to pledge his whole heart to only one woman, with the promise that he would be true to her forever. Accompanied by his lyre or harp, he’d sing his heart out in the presence of his lady and the members of the court to which she belonged.

This explosion of song and poetry that started in France spread to Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Hungary and Scandinavia, each of which created its own variations. Through them, love staked out its place not only as a literary concept but also as an important social value and an intrinsic part of being human. A yearning for amorous love seeped into the Western consciousness and has remained there since. The illustration (above) is from the German Codex Manesse, a compilation of love poems which historians place sometime between 1300 to 1340. Between the couple, a fanciful tree rises to form the outline of a heart, which carries within it a coat of arms bearing the Latin word AMOR (love.)

In 1344, the first known image of the indubitable heart icon with two lobes and a point appeared. It made its debut in a manuscript titled The Romance of Alexander, written in the French dialect of Picardy by Lambert le Tor (and, after him, finished by Alexandre de Bernay). With hundreds of exquisitely ornamented pages, Alexander is one of the great medieval picture books.

The scene containing the heart image appears in the lower border of a page decorated with sprays of foliage, perched birds and other motifs characteristic of French and Flemish illumination. On the left-hand side (above), a woman raises a heart that she has presumably received from the man facing her. She accepts the gift, while he touches his breast to indicate the place from which it has come. From this moment on, there was an explosion of heart imagery, particularly in France.

During the 15th century, the heart icon proliferated throughout Europe in a variety of unexpected ways. It was visible on the pages of manuscripts and on luxury items like brooches and pendants. The heart also turned up in coats of arms, playing cards, combs, wooden chests, sword handles, burial sites, woodcuts, engravings and printer’s marks. The heart icon was adapted to many practical and whimsical uses, with most — but not all — related to love.

Frenchman Pierre Sala contributed to the history of the amorous heart with a book titled Emblèmes et Devises d’amour, or Love Emblems and Mottos, prepared in Lyon around 1500. His collection of 12 love poems and illustrations was intended for Marguerite Bullioud, the love of his life, although she was married to another man. (She and Sala wed after her husband’s death.) Sala’s tiny book was meant to be held in the palm of one’s hand. In one of the illustrations (above), two women attempt to catch a bevy of flying hearts in a net stretched out between two trees. The winged heart, borrowing from angels, had already appeared in earlier illustrations as the sign of soaring love.

Though some people assume that Valentine’s Day is the creation of the modern greeting card industry, its history is much older — indeed, so old that its origins are clouded. Saint Valentine of Rome was added to the Catholic calendar by Pope Gelasius in 496, to be commemorated on February 14, the same day it still occupies. While there have been various theories of why St. Valentine became associated with love, it most likely developed during the late Middle Ages in the context of Anglo-French courtly love.

By the mid-17th century, the celebration of Valentine’s Day in England was customary for those who could afford its rituals. Affluent men drew lots with women’s names on them, and the man who picked a lady’s name was obliged to give her a gift. The earliest English, French and American valentines were little more than a few lines of verse handwritten on a sheet of paper, but over time, makers began embellishing them with drawings and paintings. These were folded, sealed with wax, and placed on their intended’s doorstep.

Then, the first commercial valentines appeared in England at the end of the 18th century. They were printed, engraved or made from woodcuts and sometimes colored by hand. They combined traditional symbols of love — flowers, hearts, cupids, birds — with doggerel verse of the “roses are red” variety. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, mass-produced Valentine’s Day cards obliterated the handmade variety in England and the US. The French, too, began exploiting the commercial valentine, with cards featuring angel-like cupids surrounded by hearts (above, a French card, circa 1900).

In 1977, the heart icon underwent yet another transformation when it became a verb. The “I ❤ NY” logo was created to boost morale for a city in crisis. Trash piled up on the streets, the crime rate spiked, and it was near bankruptcy. Hired to design an image that would increase tourism, graphic designer Milton Glaser created the famous logo (above) that has since become a cliché and a meme. With the logo, Glaser extended the heart’s meaning beyond romantic love to embrace the realm of civic feelings and thereby opened the gateway to new uses. Once it became a verb, ❤ could connect a person with any other person, place or thing.

Twenty-two years later, a new graphic form appeared that brought the heart into a whole new realm. In 1999, Japanese provider NTT DoCoMo released the first emojis made for mobile communication. In the original set of 176 symbols, there were five concerning the heart. One was colored completely red, one included white blank spots to suggest 3-D depth, another had jagged white blanks at its center signifying a broken heart, one looked as if it were in flight, and one had two small hearts sailing off together.

Now there are more 30 different emojis containing a heart, and I suspect the heart image will keep evolving in unknown ways for centuries to come. While the heart may be only a metaphor, it serves us well, for love itself is impossible to define. Throughout the ages, men and women have tried to put into words the various shades of love they’ve experienced — fondness, affection, infatuation, attachment, endearment, romance, desire or “true love.” But when words fail us, we fall back on signs. We add ❤ to our emails, texts and notes. We send valentines adorned with ❤ to those dear to us. We give gifts with❤ patterns. We make ❤ -shaped cookies for children. The continued global popularity of the heart as a symbol for love offers us a small dose of hope, serving as a reminder of the ageless assumption that love can save us.

This story was adapted from Marilyn Yalom’s TEDx talk and from her book The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love, with the permission of Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group. Copyright © Marilyn Yalom 2018.

Watch her TEDxPaloAlto talk here: