In today’s partisan landscape, thoughtful and open discussions about the big issues can sometimes be hard to find. Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman are turning to art — including highway billboards and remakes of revered images — as a way to catalyze conversations and reinvigorate democracy.

You might consider artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman to be provocateurs. But rather than trying to stir outrage or drum up publicity, they’re using their art — and the work of others — to provoke thoughtful public conversations about America’s most contentious issues and its most deeply held values. Willis Thomas (TED talk with Deborah Willis: A mother and son united by love and art) and Gottesman are the cofounders of For Freedoms, a nonprofit organization that holds exhibits, town halls and public art campaigns as “a platform for creative civic engagement, discourse, and direct action.”

They believe that politics isn’t the problem; partisanship is. “Partisanship is about division,” says Gottesman. “We are against notions of division; we’re trying to break down the binary, not just in terms of how we define ourselves but in how we relate to one another.” For the 4th of July, we highlight some of their work that explores and interrogates what it means to be American.

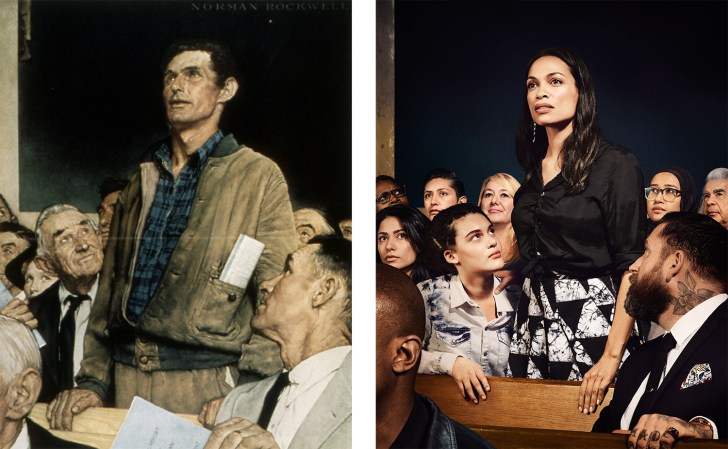

Their group, For Freedoms, was named for Norman Rockwell’s iconic Four Freedoms paintings, which in turn were inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address. In the speech, Roosevelt described what he considered to be the four fundamental human freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. When Rockwell translated these ideas into paintings, they became instant classics, entering the American visual vernacular.

Rockwell’s series is still familiar to many of us in the 21st century, yet it now seems sadly dated due to its homogeneous, mostly white, mostly middle-class characters. In late 2018, Willis Thomas teamed up with photographer Emily Shur to pay homage to that imagery, with a number of twists. While Rockwell’s series consisted of just four paintings, Willis Thomas and Shur decided to create 82 photos that included people of color, such as actor Rosario Dawson (ab0ve). In the image, she stands to speak, similar to the man in Rockwell’s original “Freedom of Speech,” but unlike him, she is surrounded by a multicultural crowd. In the pair’s take on Rockwell’s “Freedom of Worship,” (below), the faces shown reference a variety of faiths.

Last year, for the US midterm elections, For Freedoms launched their largest project: the 50 State Initiative, in collaboration with more than 250 artists and 200 museums, libraries and universities. Besides putting up 52 different, Kickstarter-funded billboards (one for each state and also one in Washington, DC, and one in Puerto Rico), the organization also held town-hall discussions and art exhibitions intended to get out the vote. “We curated the artists based on issues they might be dealing with that could inspire conversations in public,” says Willis Thomas.

Among the participating artists were Carrie Mae Weems, Emily Hanako Momohara, Zoe Buckman, Xaveria Simmons, and TED speakers Titus Kaphar (Can art amend history?), Theaster Gates (How to revive a neighborhood with beauty, imagination and art) and Dread Scott (How art can shape America’s conversation about freedom), as well as TED Fellow Sanford Biggers (An artist’s unflinching look at racial violence). The billboards were placed all over — standing along major highways and sleepy roads; plastered on city walls; or tucked into rural pockets.

The billboards, along with the related events, were meant to “suggest” rather than “declare” — to provoke questions and conversations, not arguments and debates. “In America, the billboard has become a part of our sky, part of our natural landscape,” says Simmons, a multimedia artist who had also collaborated with For Freedoms in 2016. “A billboard is often directly tied to how people spend their money, so it’s interesting to take up that air space for an artistic agenda instead.”

Her billboard (above) was meant to challenge the idea that freedom is guaranteed. “But there’s a kaleidoscope of ways it can be viewed,” says Simmons, who typically works with sound, performance, sculpture and photography to address subjects like memory and identity. “The freedom of the female body — and the black body — is definitely not guaranteed,” she says. “But some people might look at the billboard and embrace the message as part of their right to bear arms.”

Although For Freedoms says it “aims to inject anti-partisan, critical thinking” into public discourse, the artists involved in the 50 State Initiative were free to advocate for what they believed in. Many of the billboards provide commentary on multiple levels, swathed in a polished advertising veneer. “We’ve worked with different designers to create more of an advertising aesthetic so the billboards don’t just look like a straight public-service announcement,” says Willis Thomas. “We want to stay true to the artist’s vision while also [provoking questions] like: Is this an ad? Is it art? Is this critical? Is something for sale?”

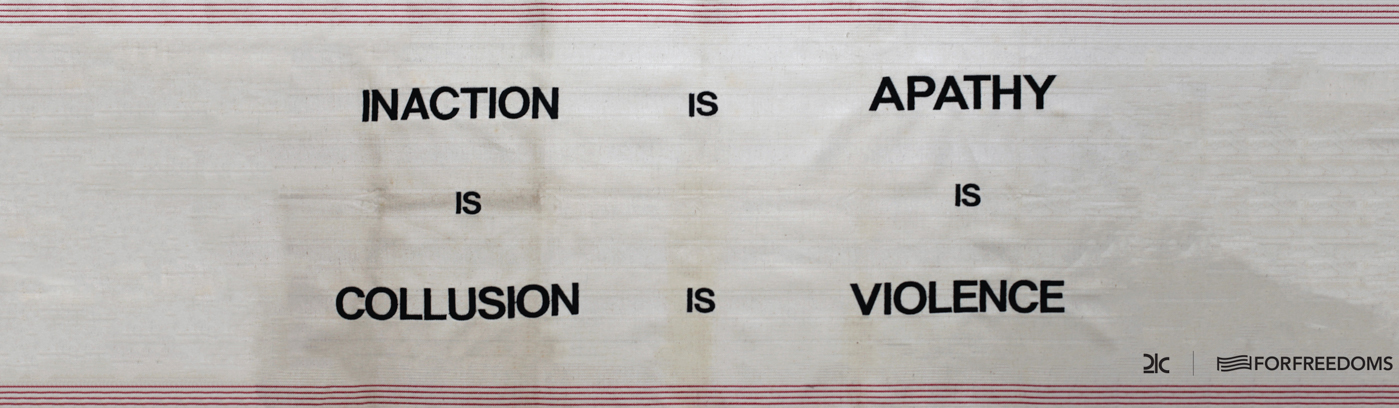

Feminist artist Zoe Buckman sees the organization’s goal as “challenging people’s perception of their own accountability. I’m hoping to raise a little consciousness and shine some light on the idea of responsibility.” Her billboard (above) urged the public to consider the implications of inaction and apathy.

“Inaction Is Apathy,” part of a series of quotations that Buckman embroidered onto vintage tea towels, was inspired by the killing of Nia Wilson, an 18-year-old black woman who was stabbed to death in Oakland, California, in July 2018 by a white man. “The work is speaking to violence [including] domestic violence and sexual violence,” Buckman says. “I think we all have a responsibility to take part in what’s going on in our country at the moment. If you don’t, you’re part of the problem.”

Unlike the usual town halls, which are led by politicians and other government officials, For Freedoms’ town halls tend to be led by artists like Buckman. “To say that art is not political is to be very naive about the practitioners of art throughout the ages. We live in a political world,” says Simmons. “Artists are readers, thinkers, engagers. If they’re thinking about their identity, that’s political; if they’re thinking about their race or sexuality, that’s political.”

True to the organization’s mission, the town halls are about bringing people together to talk. Since For Freedoms is not affiliated to a specific political group, they’re attempting to bridge the gaps between parties and factions and create spaces for communities to learn from one another. “Part of what we want to do is figure out a way for us to forge a new civic vocabulary around how we can talk to each other, how we can disagree, and yet still be part of a productive, communal conversation.” says Willis Thomas.

By using a creative lens to look at America’s pressing problems, the founders of For Freedoms and the participating artists are trying to add depth and nuance to debates that are sometimes sorely lacking in both. Essentially, says Willis Thomas, “art and politics are the same thing. They’re both forms of advancing humanity.” He adds, “The blurring between what is art, what is politics, what is engagement, what is education — these things are all part of the same conversation. Even when they don’t necessarily fully deliver on their promises, they are striving to do better.”

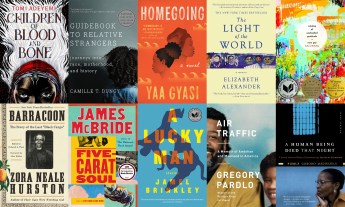

Watch Hank Willis Thomas’s TEDWomen talk now: