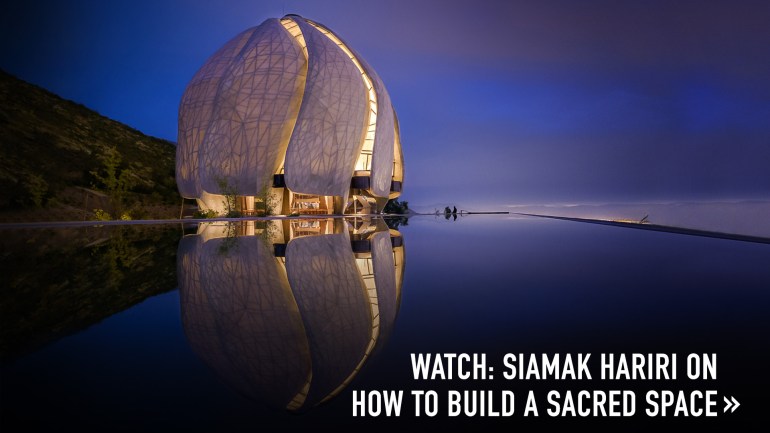

How do you design a sacred space that invites people in regardless of who they are and what they believe (or don’t)? Architect Siamak Hariri takes us into the planning and poetry behind building the luminous Bahá’i Temple in South America.

The architectural specifications for a new Bahá’i Temple of South America were minimal: to design a domed, nine-sided space with nine entrances. No need for a pulpit or dais, no choir stalls, certainly no religious statuary or paintings. But with so few constraints, the creative possibilities were endless. “It was like designing one of the first churches for Christianity, or one of the first mosques for Islam,” says Canadian architect Siamak Hariri, who is himself a Bahá’i.

In 2003, Hariri’s Toronto-based firm, Hariri Pontarini Architects, beat 184 other submissions to win the competition to create the Temple in Santiago, Chile, which would be the faith’s eighth continental House of Worship. While Hariri was inspired by the first House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois, he didn’t want his building to replicate any existing religious or cultural structures. “It couldn’t just look like a mosque, synagogue, cathedral, opera hall or art gallery,” he says. “We relied on the furthest reaches of our imagination … aspiring for ineffable qualities of beauty, sensuousness and emotion.”

Over the next 13 years, Hariri faced numerous challenges — real estate, material, structural, even seismic — before finally unveiling his graceful glass and marble structure in fall 2016. Here, he reflects on the labor and love that went into making a sacred space in modern times.

A welcoming beacon

Founded in 19th-century Iran by the prophet Bahá’u’lláh on the principles of unity, inclusion, equality and service, the Bahá’i faith has an estimated five million to seven million followers worldwide. The hunt for the right place to build in Santiago — which had been selected by Bahá’i officials as the location for the South American Temple — took Hariri five years as he cycled through several locations. One day, he and his team were taken to the grounds of a private school. Hariri wandered half a kilometer from where he was dropped off and suddenly, he recalls, “I just felt the tempo. I said, ‘This is it.’ The combination of the [Andes] mountains and the city right there at that elevation was absolutely perfect.” He drove a stake in the ground at the spot, and after intense negotiation, ten hectares of land were theirs. The main entrance of the Temple faces Qiblih, the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh located near Acre, Israel, and where Bahá’ís look toward when saying their daily prayers.

A structure that grows toward the sun

Rather than turning to the architectural world for ideas, Hariri opened himself to the natural one. While dreaming up his design, he saw a time-lapse video that showed how seedlings twist and grow towards the light. He was captivated by the simple, instinctive behavior; he also saw it as a physical metaphor for prayer. “You’re reaching, you’re moving. It requires effort,” he says of praying. “You can’t just sit back. I thought the space should somehow try to capture the feeling of movement.” Other sources of inspiration for him were the curve of a human cheekbone, the flow of the skirts of whirling dervishes, the elegance of a woven Japanese bamboo basket, and the swirls of the white calligraphic paintings of American artist Mark Tobey (also a Bahá’i). Hariri wanted the walls of the temple to share the same sense of natural, rhythmic flow as those points of reference.

A nine-pointed star spinning in space

The Temple consists of nine “luminous veils,” as Hariri calls them, with nine bronze doors and nine pathways — the number nine holds deep significance in the Bahá’i faith, representing unity and perfection. Nestled between each pair of paths is a lily pond (this photo shows the building under construction and before the ponds, the green spaces, were filled). The rectangular shape at the upper right became a reflecting pool that greets people when they arrive at the Temple. In keeping with Hariri’s theme of movement, the building when viewed from above seems as if it’s been frozen in mid-revolution. “The idea of moving and revolving around a center is very much in the Bahá’i writing, and in all religions [there’s] the idea that universe has a center and that things revolve and move in a circular motion,” he says.

A building alive with light

Besides movement, another main theme for the Temple was what Hariri calls “embodied light.” He was moved by a passage in the Bahá’i writings that describes becoming “ashine with [Divine] light” through prayer. So he sought materials that would not just reflect light but also glow from within. For the exterior of the building, he and his team worked with fabricators to create a new kind of cast glass made of borosilicate, which has the effect of absorbing light. Inside this facade, Hariri wanted a stone lining — he envisioned alabaster which has a translucent glow when lit. However, after winning the competition, he discovered that alabaster turns opaque under heat (temperatures at the site can exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit), so instead he searched marble quarries until he found a rare vein in Portugal. “When it receives just a kiss of light, the whole piece of stone comes alive,” says Hariri. “The light does not go through it, but it becomes captured within the membrane.”

The science behind a spiritual space

Hariri and his team used CATIA modeling software, used primarily by aerospace engineers, to design the twisting, three-dimensional form he had envisioned. At 88 feet high and 33 feet wide, each of the veils consists of 1,129 flat and curved pieces of cast glass. Kilns at a foundry in Toronto fired for two-and-a-half years to produce the pieces that were shipped to Germany to be finished and then attached to aluminum framing. The stone interior is made of 7,800 individually-cut marble slabs — each piece is a unique shape, a nod to the Bahá’i idea of unity within diversity — that were mounted on steel rods.

To add to the project’s complexity, the entire puzzle-like structure needed to be earthquake-proof. The building sits in a highly active seismic zone, so Hariri and his team consulted with scientists at the University of Toronto and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile to develop technology to conquer this obstacle. “[Together] they devised a pendulum isolation system that allows for 600 millimeters of movement,” says Hariri. Each wing rests on an elastomeric seismic isolator, “so in the event of an earthquake, it rocks [horizontally] and returns to the center.”

A space for everyone to worship in their own way

The bulk of the 26,000-square-foot Temple is a circular room which holds 600 people. “It should be a place where you feel connected to your inner life, as well as the Divine. It is meant to … say, ‘This is everyone’s temple,’” Hariri says. “In these divisive times, when the world is putting up walls, the design needed to express in form the very opposite.” Besides the leather-and-walnut seating, the veils’ undulations offer spaces for prayer and contemplation. The building — which was budgeted to cost $30 million and, as Harari proudly notes, came in within three percent of that amount — was entirely funded by followers’ donations.

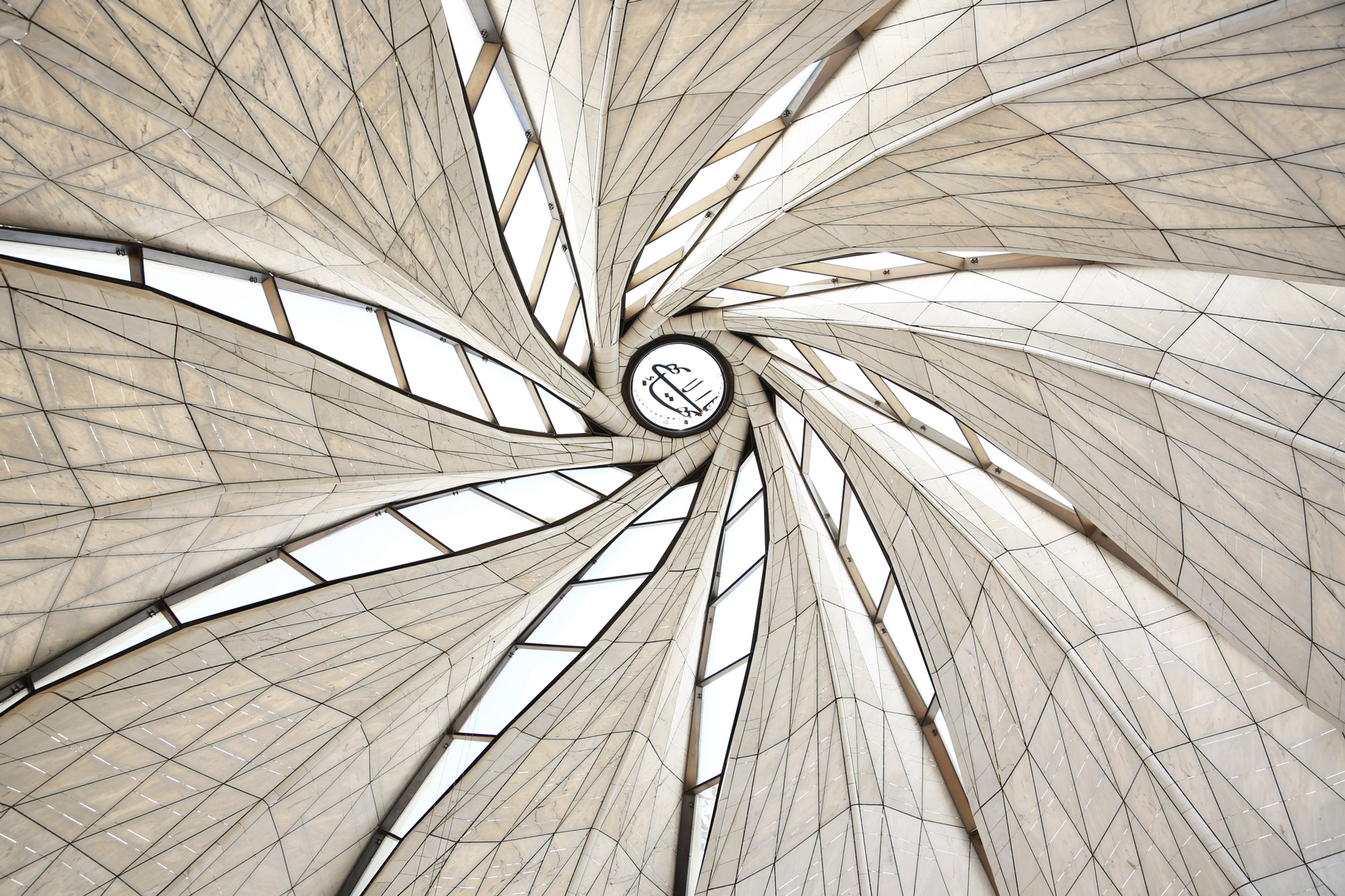

An elegant eye to the heavens

“The earliest temples used to have a hole at the top,” Hariri says, citing the Pantheon in Rome as one example. In his South American Temple, a glass oculus in the ceiling contains an Arabic calligraphic wood carving that was crafted by Chilean artisans from roble beech, a tree native to the country. It translates to mean “O Thou Glory of the Most Glorious.” (The Bahá’i also refer to it as the Greatest Name.) The symbol, which is the sole piece of iconography in the space, floats at the Temple’s apex where the main walls converge and symbolize the interconnection of all things. Inside the wood carving is a case holding dust from the the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh, joining it to the spiritual center of the Bahá’i faith. Hariri describes the skylight-like oculus as “an eye to the heavens,” allowing all movement inside to reach towards the light and, ultimately, to God.

A temple that invites reflection

Hariri designed the Temple so that visitors encounter it gradually, ascending a long stairway (or ramp) before they reach a terrace with a reflecting pool. Chilean landscape architect Juan Grimm filled the surrounding gardens with plants and trees indigenous to the region. Hariri says that everyone sees something different — a sprouting seed, an egg, a flower — when they look at his construction. Since its opening in October 2016, the temple has attracted thousands of visitors. “I love that indigenous people from all over South America, from remote parts of Peru, Uruguay, Bolivia, are comfortable within it,” Hariri says. “It doesn’t matter whether you’re the poorest of the poor or the richest of the rich. Here, everyone has a rightful place and a connection.”