“It has been 128 years since the last country in the world abolished slavery and 53 years since Martin Luther King pronounced his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech,” says Brazilian artist Angélica Dass (TED Talk: The beauty of human skin in every color). “But we still live in a world where the color of our skin not only gives a first impression, but a lasting one that remains.” She shows off Humanae, the photo project she started to highlight the truly multi-colored hues of humankind.

The glory of individuality

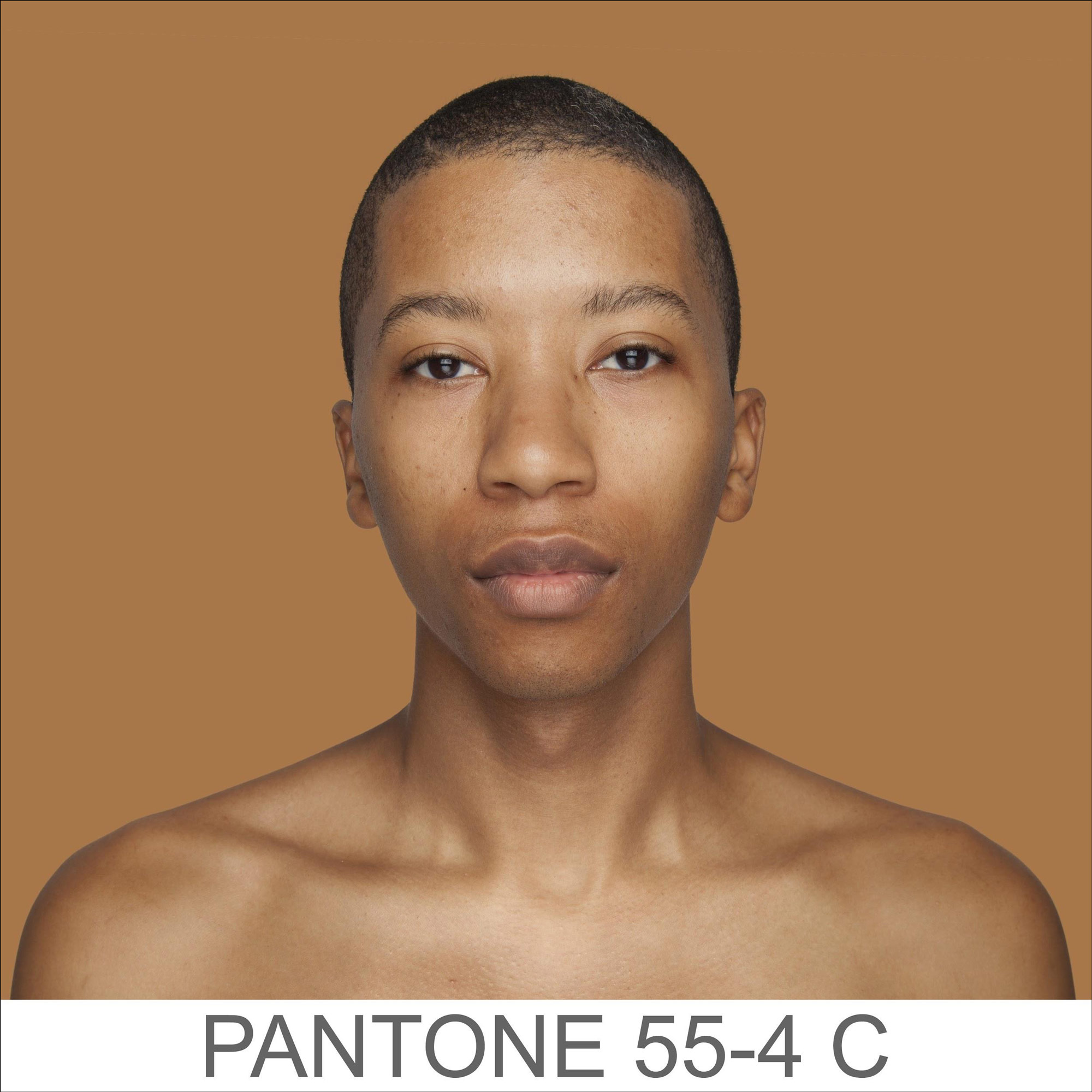

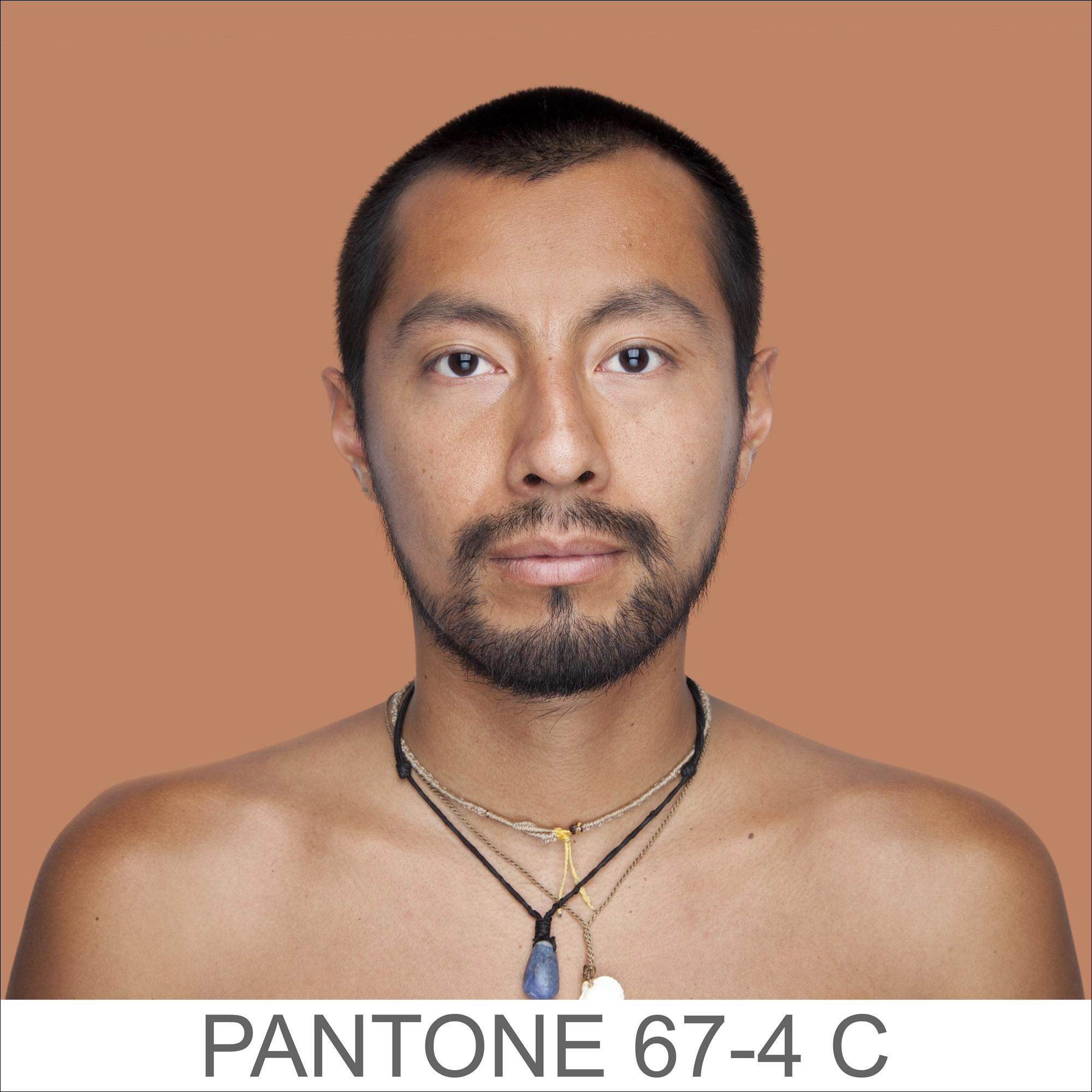

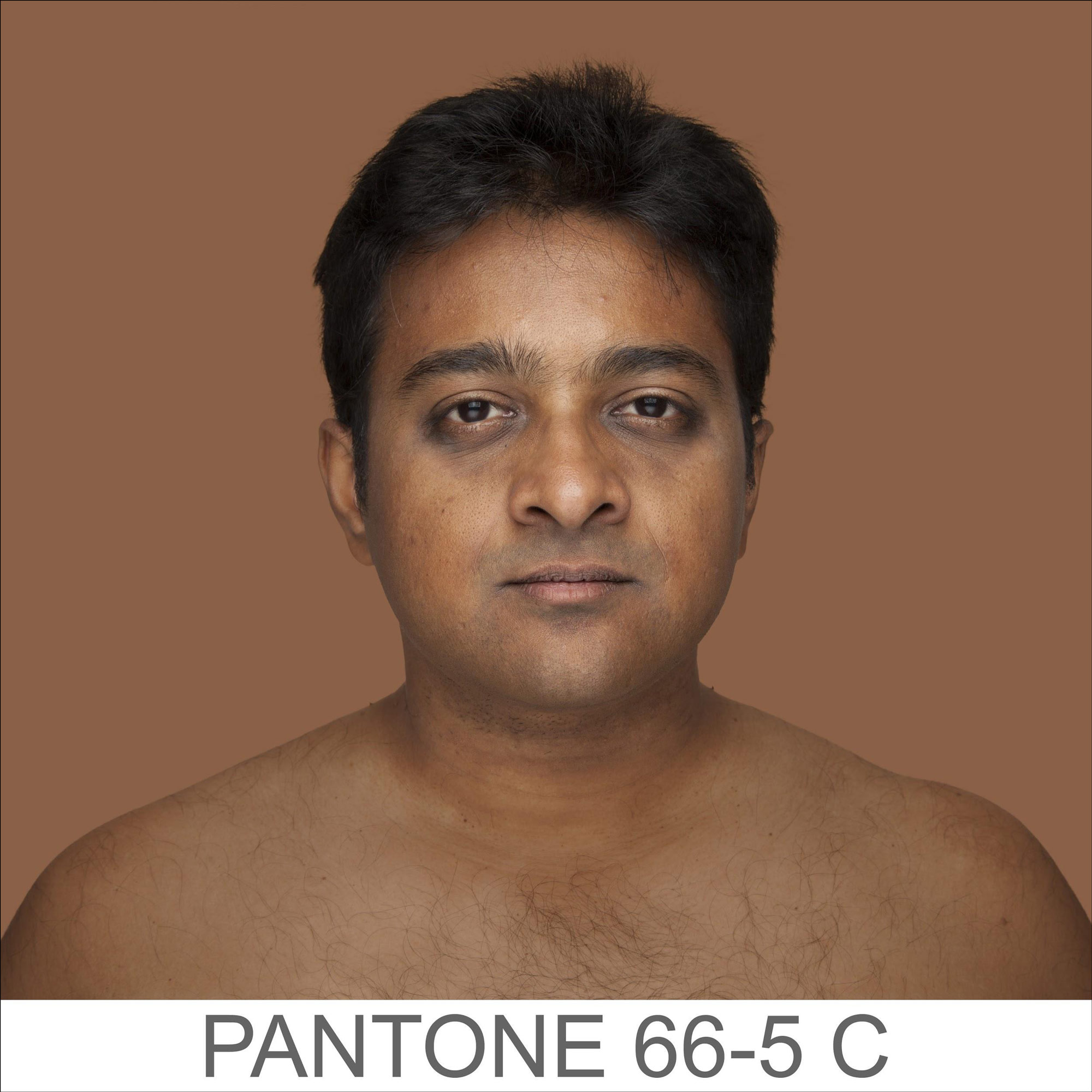

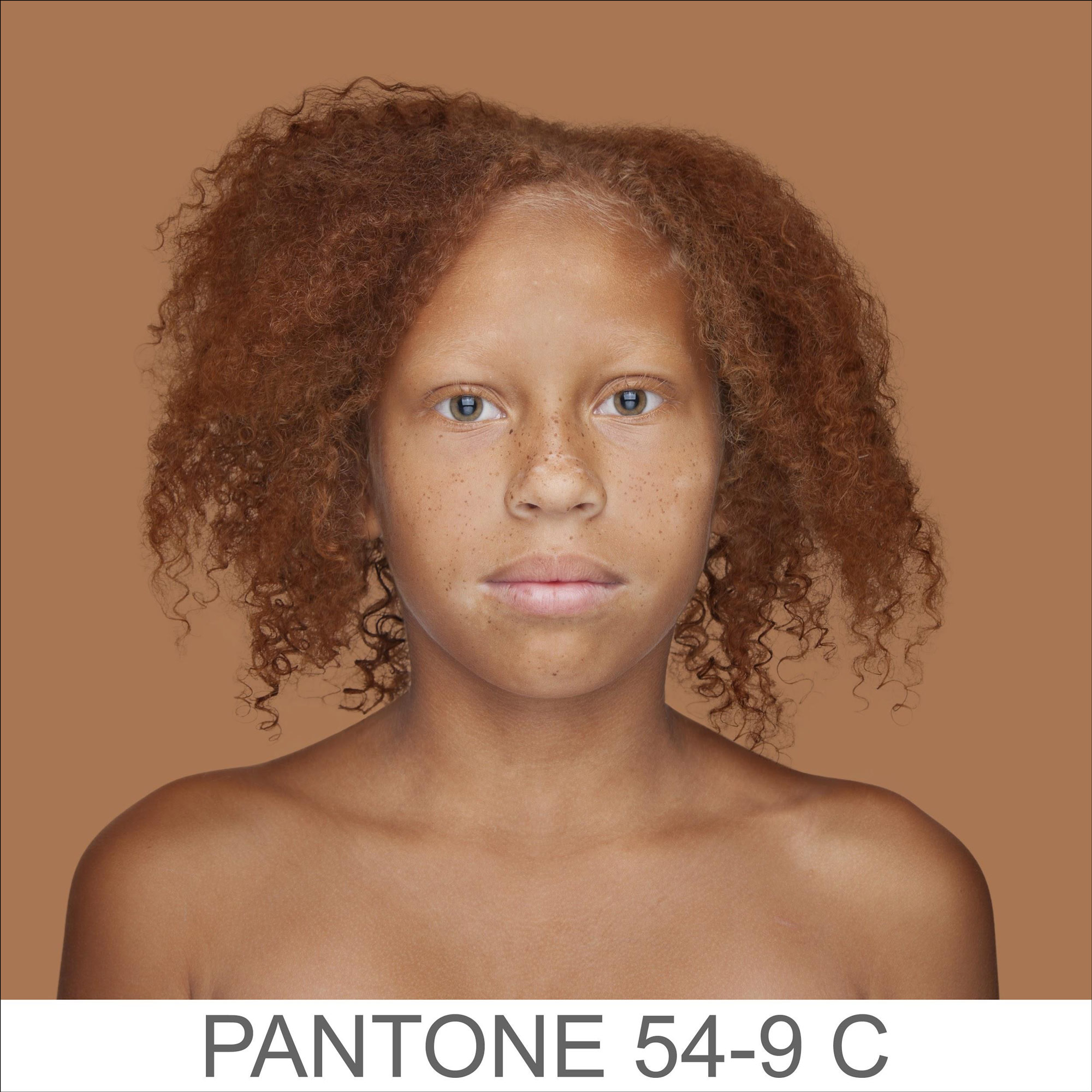

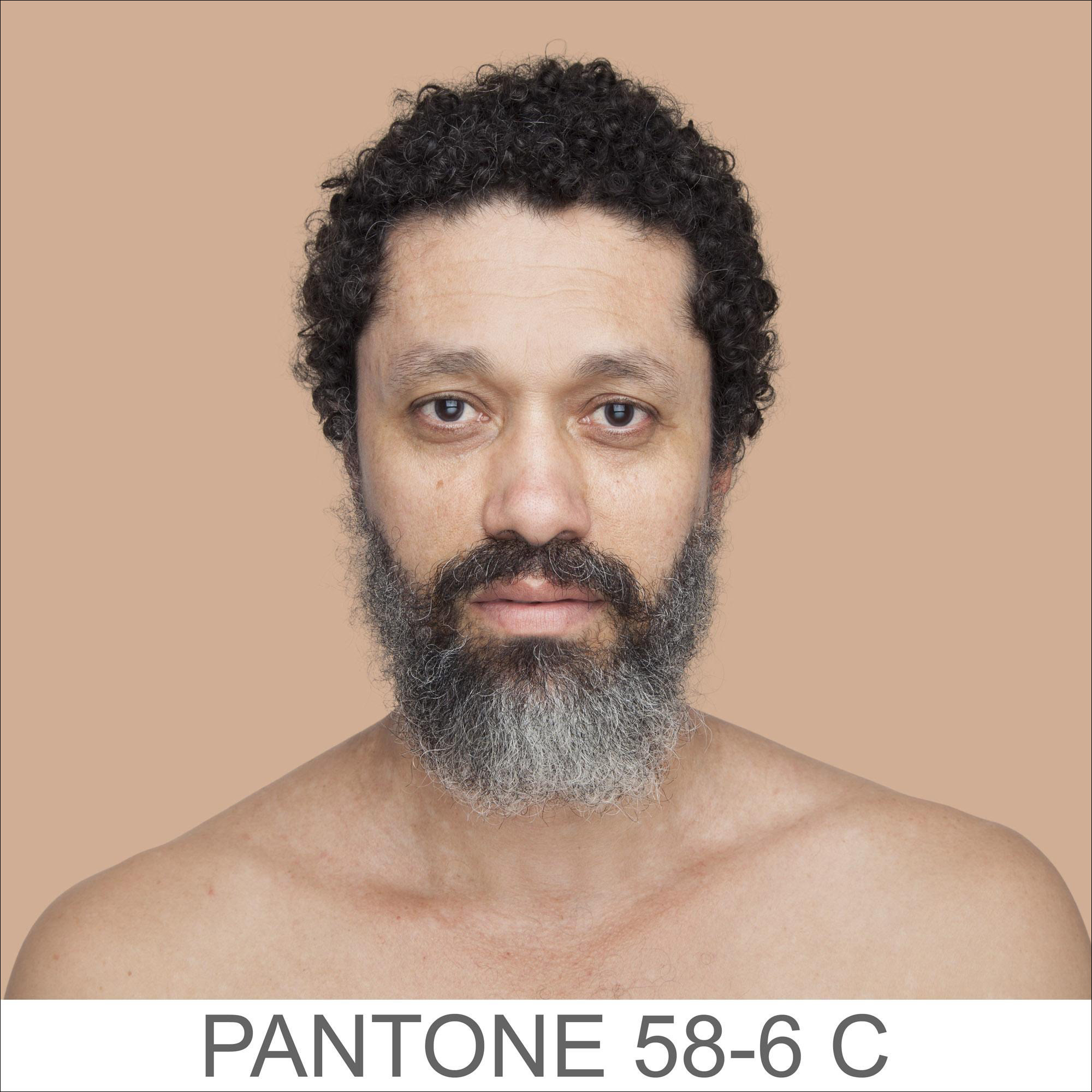

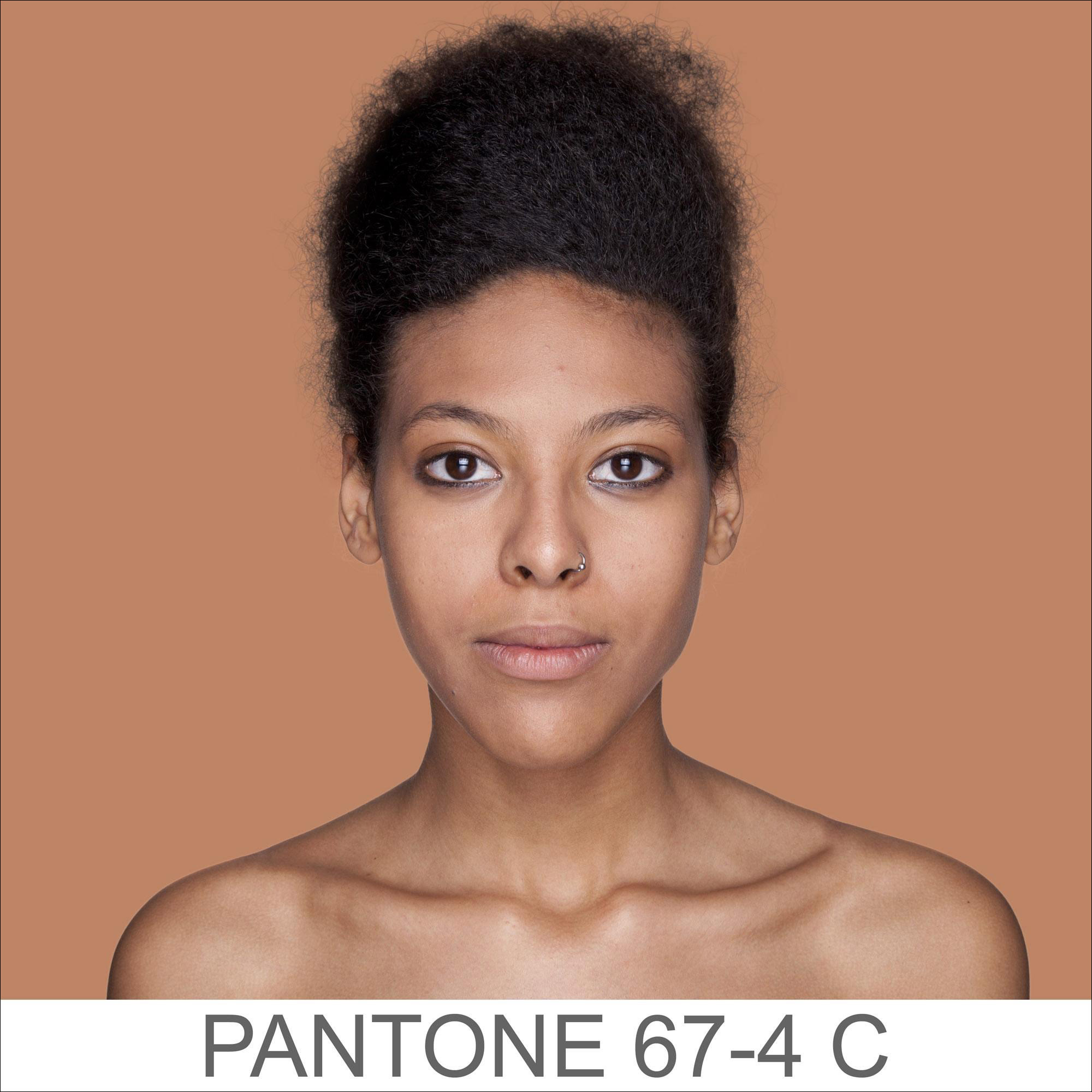

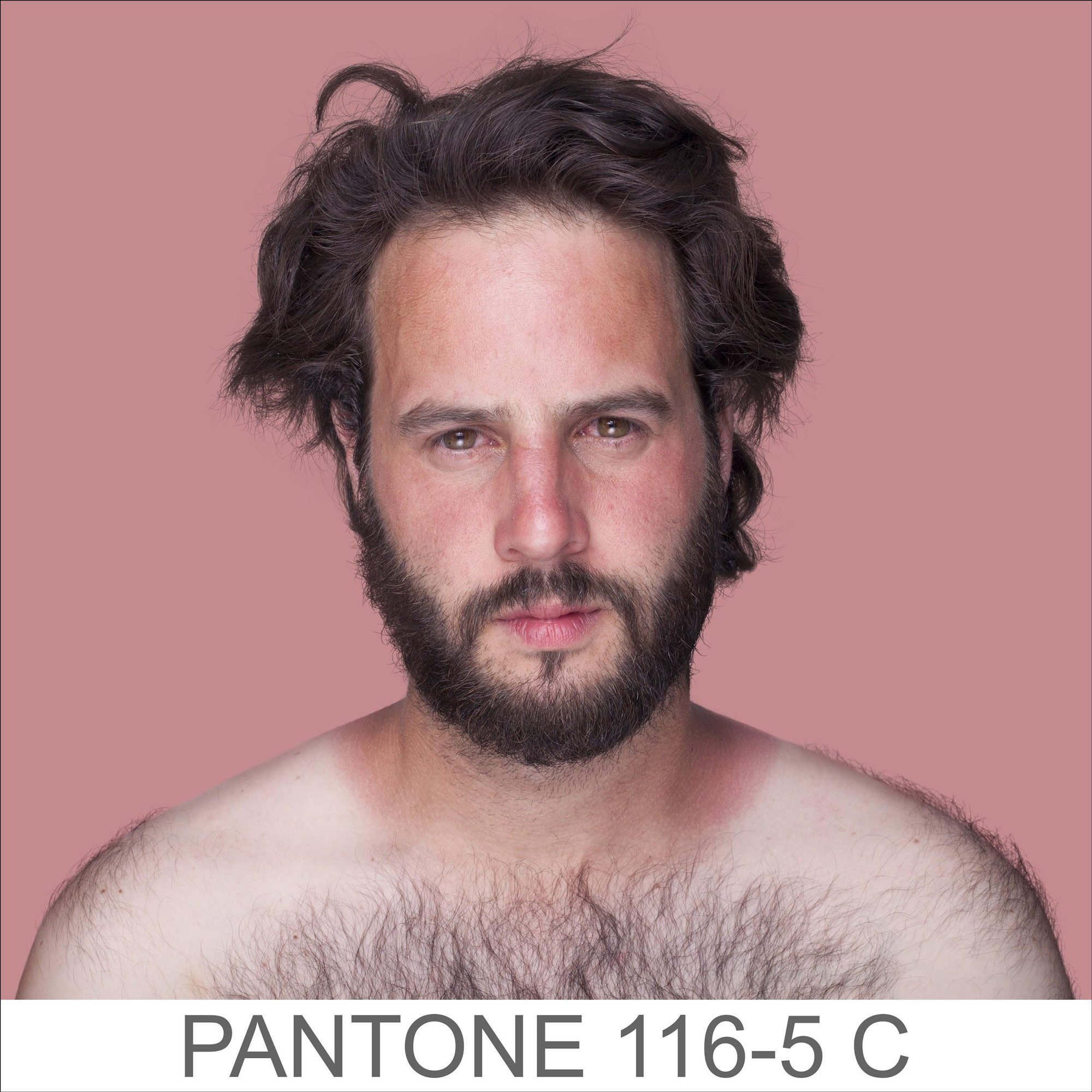

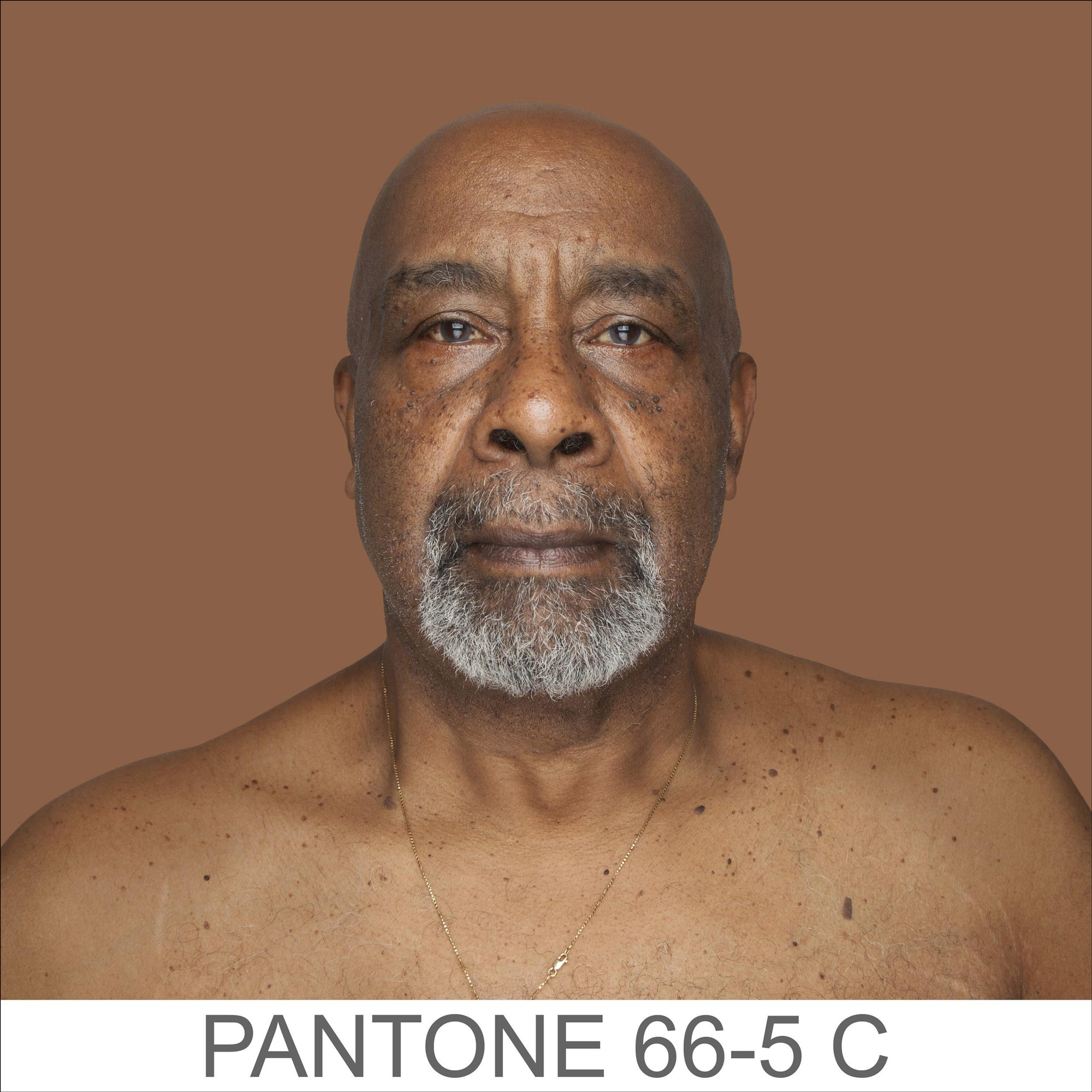

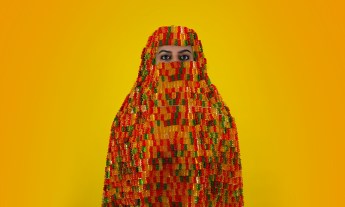

“Humanae is a pursuit to highlight our true colors rather than the untrue white, red, black or yellow associated with race,” says Dass. “It’s a kind of game to question our codes. It’s a work in progress from a personal story to a global history.”

It’s all about the nose

“I portray the subjects in a white background,” says Dass of her process. “Then I choose an 11-pixel square from the nose, paint the background and look for the corresponding color in the industrial palette, Pantone.”

All welcome

“I started with my family and friends, then more and more people joined the adventure, thanks to public calls coming through the social media,” she says. “I want an open concept that invites everybody to push the share button in both the computer and their brain.”

We are the world

“The project had a great welcome — invitations, exhibitions, physical formats, galleries and museums … just happened,” Dass says. “Among them, my favorite: when Humanae occupies public spaces and appears in the street.” Such different contexts, she says, foster a popular debate and create a feeling of community.

The world is full of colors

So far, Dass has taken pictures of more than 3,000 people in 19 different cities in 13 different countries. Anyone is welcome; portraits include everyone from “someone included in the Forbes list to refugees who crossed the Mediterranean by boat,” she says, while she has photographed in locations ranging from UNESCO headquarters to favelas in her native Brazil. “All kinds of beliefs, gender identities or physical impairments, a newborn or terminally ill,” she says make up her new tribe. “We all together build Humanae.”

What’s the definition of flesh-colored, anyway?

Humanae had a very personal starting point for Dass, who describes herself as born into a family “full of colors.” She says that at school she was confused by the idea of depicting people. “I never understood the unique flesh-colored pencil,” she says. “I was made of flesh but I wasn’t pink. My skin was brown, and people said I was black. I was seven years old with a mess of colors in my head.”

Humanity far beyond the art world

The project appeals beyond its obvious aesthetics. Dass says she has been surprised and honored to see the project find new life outside of the artistic context. “Researchers in the fields of anthropology, physics and neuroscience use Humanae with different scientific approaches related to human ethnicity, optophysiology, face recognition or Alzheimer’s,” she says.

What’s your color?

Meanwhile, her number one fanbase is made up of teachers, who use Humanae as a tool for educational purposes. “Their passion encourages me to go back to drawing classes, but this time as a teacher myself,” says Dass. “My students, both adults and kids, paint their self-portraits, trying to discover their own unique color.”

Let there be love

“As a photographer, I realize that I can be a channel for others to communicate,” she says. “As an individual, as Angélica, every time I take a picture, I feel that I am sitting in front of a therapist. All the frustration, fear and loneliness that I once felt … becomes love.”

A mirror for mankind

Hundreds of people have shared their response to the pictures with Dass. “Suddenly I realized that Humanae was useful for many people,” she says. “It represents a sort of mirror for those who cannot find themselves reflected in any label. It was amazing that people started to share their thoughts about the work with me.”

Every portrait tells a story

“What does it mean for us to be black, white, yellow, red?” she asks. “Is it the eye, the nose, the mouth, the hair? Or does it have to do with our origin, nationality or bank account?” Her hope: these portraits make us rethink how we see each other, and maybe remind each of us both of our individuality — and our shared humanity.