Artist Janet Echelman constructs massive fiber art pieces to encourage people to stop, look up and wonder.

Standing beneath one of Janet Echelman’s giant, airy, uplifting pieces, you might just think a group of groovy extraterrestrial spiders have come to pay us a visit.

The pieces, woven from strong, light fibers and tinted in rainbow colors, sway and flow in the sky, turning blank urban spaces between buildings into a place of magic.

What does it take to create one of these massive spiderwebs — spanning the size of city blocks, anchored to multiple buildings, and stable in the strongest wind (as well as safe for passing birds)? A very, very close-knit team.

As Echelman tells us (TED talk: Taking imagination seriously), each soft sculpture begins as a vision in her head, as she thinks about the site and the commission. In her Boston studio, she and a design team use custom software to turn her vision into a virtual 3D model. Then they turn to dozens of professionals to make it real.

“We work with aeronautical and structural engineers, lighting designers, architects, city planners, administrators and permitters. We’re doing a piece now where there’s an aviation permit specialist,” says Echelman. “And then there are all of my fabricators: the people who make my custom-colored fibers, my braided twines and ropes; my loom workers; hand-splicing artisans; general contractors; crane operators; riggers and installers; and museum curators.”

Echelman’s work relies on relationships, and she sees themes of interconnection and community flowing through her art. “In my sculptures, if a single knot moves, every other knot is affected at every moment,” she explains. “I feel my work is a manifestation of the interconnectedness of various parts of our planet and how we are all moving together in a web. Making art is my way of trying to make sense of the world.”

Sculpting nets and the wind

Echelman came across her artistic medium through a mixture of chance and necessity. In 1997, she was awarded a Fulbright Lectureship and flew to Mahabalipuram, a town on the southeastern coast of India, where she would teach painting and display her art. After arriving there, she found that her special paints and tools had all been lost in transit. With nothing to exhibit, she needed to come up with an alternative fast. One evening, she watched fishers gathering their nets. She wondered: Could she use them to make a sculpture, an art form that she’d never tried before?

Echelman had great respect for traditional handicrafts — in the late ’80s and early ’90s, she’d traveled through Asia to learn Chinese calligraphy and Balinese carving. There, in India, she found tailors and fishers who helped her hand-knot nets and fasten them to curved, metal frames hoisted on poles. She made her first sculptures from cotton, silk and steel wire. “I had never studied sculpture, so I was discovering it under deadline. It was very hard and lonely,” says Echelman. “This immense pressure pushed me beyond my comfort zone — and I felt liberated.”

She called the five pieces Bell Bottoms. Their shapes were loosely inspired by the nearby, ancient Pallava Empire temples. She brought her work to the beach just so she could photograph them in an open space in the sunlight — and this led her to an artistic epiphany. “That was the moment where I discovered the interaction of wind. It was not planned,” she says. “We lifted the forms into the air, and they began to ripple in ever-changing patterns. It was a choreography that never repeated itself.” Echelman was enchanted.

Showing a tsunami’s waves

In 1999, Echelman opened a studio in New York City with a vision to build larger sculptures. She worked with engineers to build customized design software, and looked for materials that could hold up against wind and storms. In 2005, officials in Porto, Portugal, asked her to build a permanent piece that would hang over a public plaza. The result was She Changes, a one-ton circular net that ripples across the sky, suspended from a steel ring. “I remember turning the last bolt on it and when I got down off the crane, I looked at it and I couldn’t believe it was real,” she says. “It was like reading Dr. Seuss and then discovering the world you imagined is physical and real.”

Shown here is 1.26, which was commissioned for the 2010 Biennial of the Americas, a festival that connected leaders from North, South and Central America. The city of Denver gave Echelman a specific mandate: to create a piece that visually represented the interconnectedness of nations. “I was completely stumped,” she admits. “But I started researching and came across an animation of the February 2010 Chilean earthquake and tsunami. I was inspired by how an event in one part of the world can have ripple effects on every part of the planet.” The quake’s vibrations were so strong they sped up the earth’s rotation, shortening the day by 1.26 microseconds. She and her team used data sets from NASA and NOAA to generate a 3D model of the tsunami waves careening across the Pacific Ocean to Asia.

1.26 led to a structural breakthrough for Echelman. Because the sculpture would be aloft for only one month, she knew it was too costly and impractical to use the structural steel she employed for permanent pieces. She decided to made the piece out of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene fiber (UHMWPE), a low-density yarn that’s 15 times stronger than steel (it’s how NASA tethered the Mars Rover). Its lightness enabled Echelman to fasten 1.26 to the surrounding buildings.

“It was also the first time I was trying to express an idea in visual form and turning to a scientific data set for inspiration,” says Echelman. “For me, my work is rooted in the humility of what we know and don’t know, what we can predict and what we can’t. There are ripple effects we can see and understand but there are also ripple effects we don’t understand. My pieces are about a way of existing in the world where we recognize our place within these networks.”

Knitting Boston together

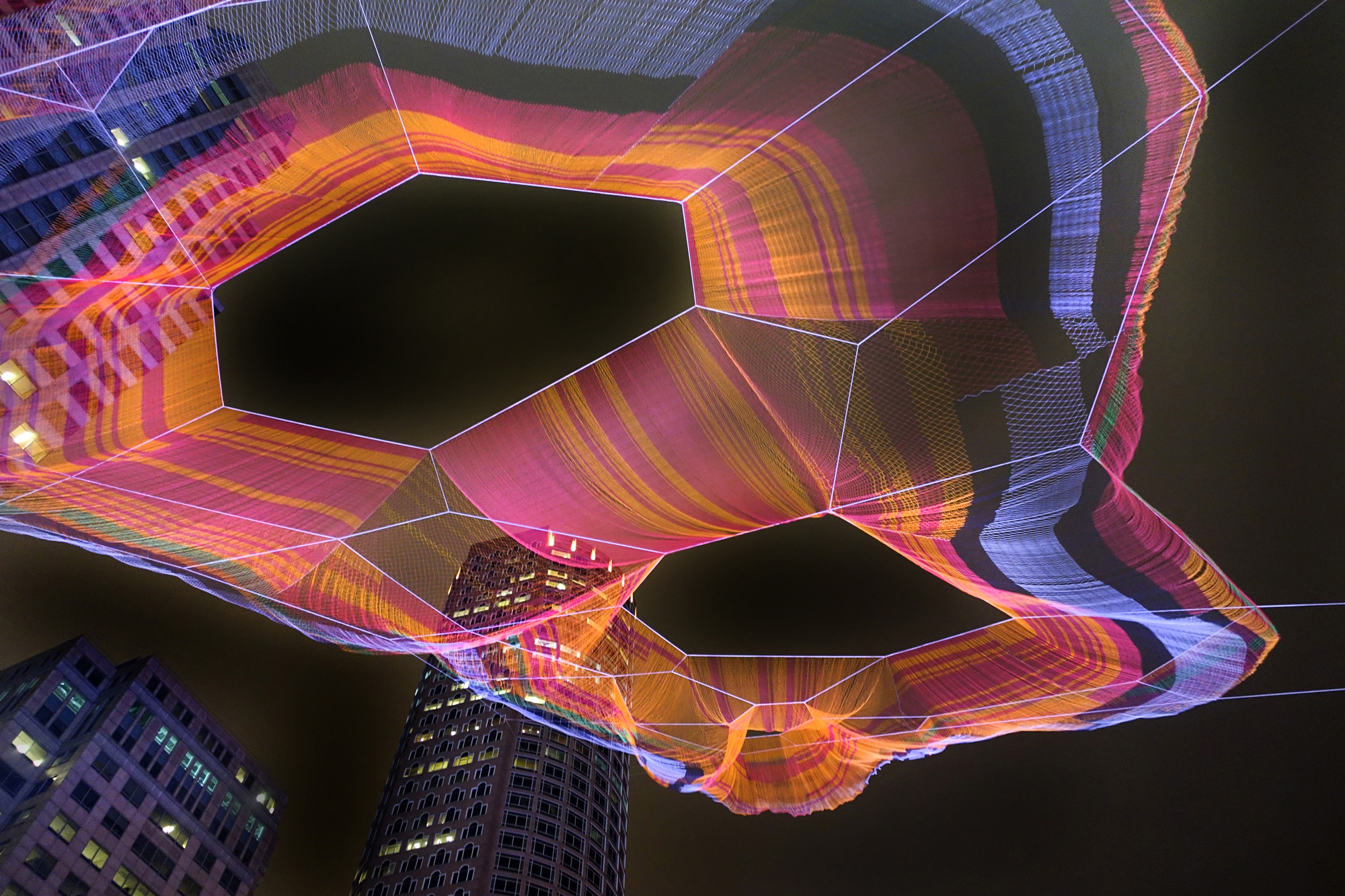

Echelman’s sculpture As if it were already here hovers above the Boston site of one of the biggest, costliest highway megaprojects in the US. Nicknamed “The Big Dig,” it took a notoriously ugly and congested highway and tunneled it underground. A vast, multi-decade project, the Big Dig cost far more than was budgeted, and construction took a decade longer than planned. But the end result? Where once a roaring elevated highway blocked Boston from its harborfront, now open space, green parks and a curving boulevard animate the streetscape.

On display from May through October 2015, Echelman’s artwork shimmered over Boston’s Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, a serene slice of nature created in the Dig’s final stages after Interstate 93 was put underground. Her goal was to “sew the city back together” in the spot where the highway once slashed through it.

Commissioned by the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy, the prismatic netting stretches 600 feet, contains more than half a million knots, and was made with more than 100 miles of high-tech twine. Its stripes nod to the highway lanes, and the three voids represent hills on the site that were destroyed back in the 18th century to create land for the Boston Harbor. “The piece references a time when automobiles were given precedence over pedestrians and human beings on the ground. It’s optimistic because we were able to acknowledge and fix a mistake like that,” says Echelman.

Connecting the city of Greensboro from above

Echelman must create her pieces amid a set of complex constraints. Each sculpture is a new puzzle to be solved, since its design has to factor in a site’s unique space, architecture, light, foot and vehicular traffic, weather, and heritage. She was awarded a grant from the Edward M. Armfield, Sr. Foundation to create a permanent installation for LeBaur City Park in Greensboro, North Carolina, that evoked the community’s past as the textile capital of the world. Once a hub for six railroad lines, it was the center of US fabric manufacturing for much of the 20th century. Echelman wanted the piece to reflect Greensboro’s identity as an important inflection point in the battle for civil rights — protesters’ nonviolent sit-ins there in 1960 led to the desegregation of Woolworth’s lunch counters.

To shape Where We Met, Echelman first drew points that corresponded to the location of each of the city’s textile mills and then began tracing in the railroads’ lines. She says, “This city is made of all of these communities that came together because of jobs and railroads. And it’s where different people are coming together today in new ways.” The 200-foot piece was constructed with 35 miles of fibers.

Echelman had to figure out how to protect the permanent piece from the heavy ice storms that occur every winter. Her solution: a winch that allows it to be easily raised and lowered. “Before winter, it comes down like a perennial flower,” she says, and it’s stored in what she describes as a “giant Tupperware”. “Then it’s lifted into the air in the spring. I like that cycle with nature where you appreciate something that hibernates because it’s gone and then returns every year.”

Inspiring a pause for thought

To make room for the 2016 installation of Echelman’s 1.8 in London, then-mayor Boris Johnson shut down Oxford Circus, one of Europe’s busiest pedestrian intersections and shopping streets. Commissioned by Lumiere London, the sculpture was part of her Earth Time series, which she started after 1.26; the name 1.8 refers to the number of microseconds that the Earth’s day was shortened due to the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

Passers-by could use their phones to choose colors and patterns that expressed their emotions. At night, these designs were projected onto the 180-foot sculpture to create what Echelman calls a “civic mood ring” of light.” She says, “I like to bring my work to cities because I think it’s a soft counterpoint to hard-edged buildings. I like to create spaces to get lost in, so there are moments of contemplation in the midst of urban life.”

Echelman was moved by people’s reactions during the four days it was exhibited. “It was January, and it was freezing cold yet people were lying down on the cold asphalt, watching the piece ripple above them,” she recalls. “One man hugged me. He was so used to bracing himself for the commercial onslaught he expected, and instead he saw the sculpture and felt a kind of generosity. It changed his whole emotional state.”

Spiraling through space and time

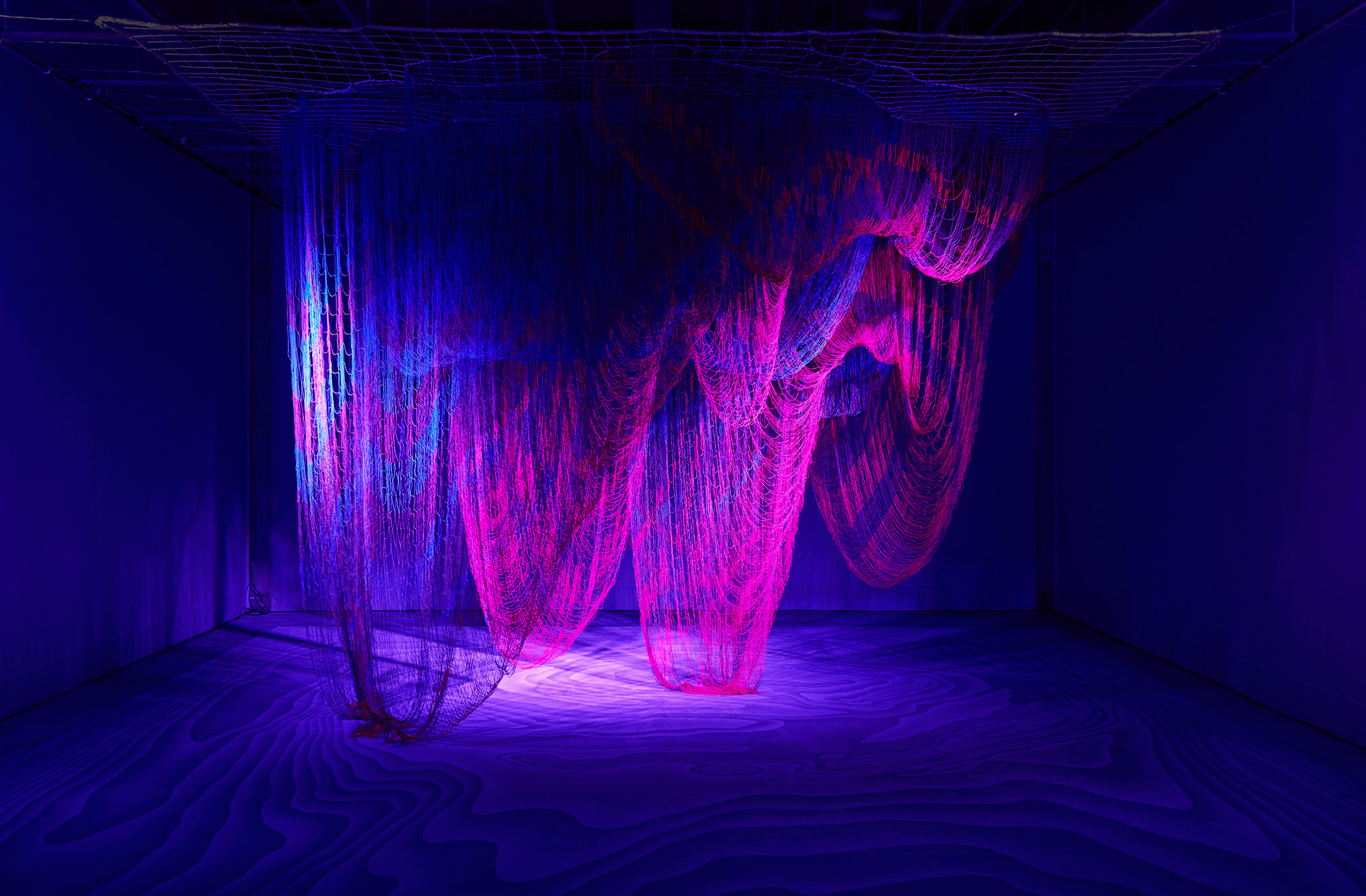

As you’ve gathered by now, time is a theme that runs through Echelman’s work. This piece was made for the 2017 Cheongju International Craft Biennale in Korea and shown at a former tobacco plant. Looped, braided twine formed an 18-f00t long curved canopy for people to walk beneath. Underfoot, a custom carpet depicts line drawings of the 3D volumes in the hanging shape above (the rug itself is, in an appropriate nod to Echelman’s Bell Bottoms, made of recycled fishing nets). The dangling twine, warmed by LED colored lights, was meant to envelope visitors and invite them to ponder the distortion of time and space, from 2D to 3D and back.

“I’d been learning about the life of Albert Einstein and his breakthrough of understanding the warping of space and time,” says Echelman. “This piece followed lines as they curve or warp a physical space, and I wanted to try to create something that would instantly transform a place into a social space.”

A colorful conversation with the past

For the 400th anniversary of Madrid’s Plaza Mayor, Echelman knew she wanted to incorporate vibrant colors into her sculpture 1.78 (a 2011 tsunami in Japan shortened the day by 1.78 microseconds) to evoke the space’s violence and rebirth over the centuries. “This is a place that fire has transformed over four centuries, from burnings during the Inquisition and Spanish Civil War to the light of the ideas of the Enlightenment,” she says. “The color serves as a dialogue with this historic place.”

On display during February 2018, the sculpture — commissioned by the city of Madrid — was roughly 100 feet by 45 feet and consisted of colored nylon and polyethylene fibers. Assisted by industrial looms, she and a team used a combination of hand-splicing and knotting to join the threads. “It’s kind of cool that we’re using the newest engineered material science together with ancient human technologies,” says Echelman. “For me, it’s important we’re not cut off from our past.”

But she’d like to make sure one important ingredient of all of her pieces is not overlooked: the viewers. She says, “Artistically, the people who come to look at my sculptures are part of the artwork for me. I think of their experience as completing the artwork. ”

Dreaming ever bigger

Dream Catcher is Echelman’s latest completed work, as well as her first multi-layered permanent piece. With a height of 90 feet and a width of 70 feet, it is installed between two 10-story towers at The Jeremy West Hollywood hotel, designed by SOM. (A test study for the sculpture is on view from June 30, 2018, to September 2, 2018, at the Poetic Structure exhibition at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles.)

Guided by a vision of dreaming guests, Echelman was researching the human brain when she came across an idea for the sculpture’s shape. She says, “I was having trouble sleeping, so I was on YouTube and stumbled upon a video about your brain waves during REM sleep.”

Looking ahead, Echelman hopes to have one of her pieces installed on every continent — including Antarctica. Currently, her permanent sculptures are in Europe (Portugal) and North America (Washington, Oregon, Arizona, North Carolina, California), and she has three permanent works planned for India, Korea and Indonesia.

“As adults, there aren’t enough opportunities for us to get lost in something,” says Echelman. “My sculptures are the size that I can lie down on the grass, look up and have it fill my world. I need moments where I can just let my mind wonder and where the physical world is suddenly transformed, so I can daydream while looking at the choreography of wind unfold.”