These precise re-creations of the world have the amazing ability to bring us up close to people and animals that are far away in space and time, says artist Aaron Delehanty.

“I build time machines,” says artist Aaron Delehanty. Actually, his specific day job is constructing dioramas — freeze-framed vignettes of animals and people in their habitats — and through them, he has transported museumgoers back to places such as southern China in 5500 BC and east Africa in 1896 (TEDxFlourCity Talk: Dioramas: part art, part science). “The intention of a diorama is to build a replica of a specific ecosystem and to do it with such precision that they become time capsules for that environment,” says Delehanty. He studied studio art and painting at the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Art Institute before he got a job constructing dioramas for the Field Museum in Chicago. He made his first diorama, a depiction of five New York Native American tribes, when he was in 6th grade, but his work today is far from kids’ stuff (although he still sometimes uses popsicle sticks). He explains the history, research and craft that inform his work.

Dioramas came out of conservation

Until the late 19th century, most museums displayed taxidermied animals and other natural specimens in aseptic rows of glass cabinets. This changed in 1890 when Carl Akeley, a taxidermist at the Milwaukee Field Museum, reimagined their presentation. What became known as the “Akeley method” involved creating a custom artificial environment — including rocks, soil, trees, sky, and whatever else was seen in the field — for a group of animals. The first example was his diorama of five muskrats in a carefully conceived set that contained a den, reeds, logs and sediment. Akeley went on to work at the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (where you can visit the Akeley Hall of African Mammals), and his exhibits influenced science and art institutions worldwide.

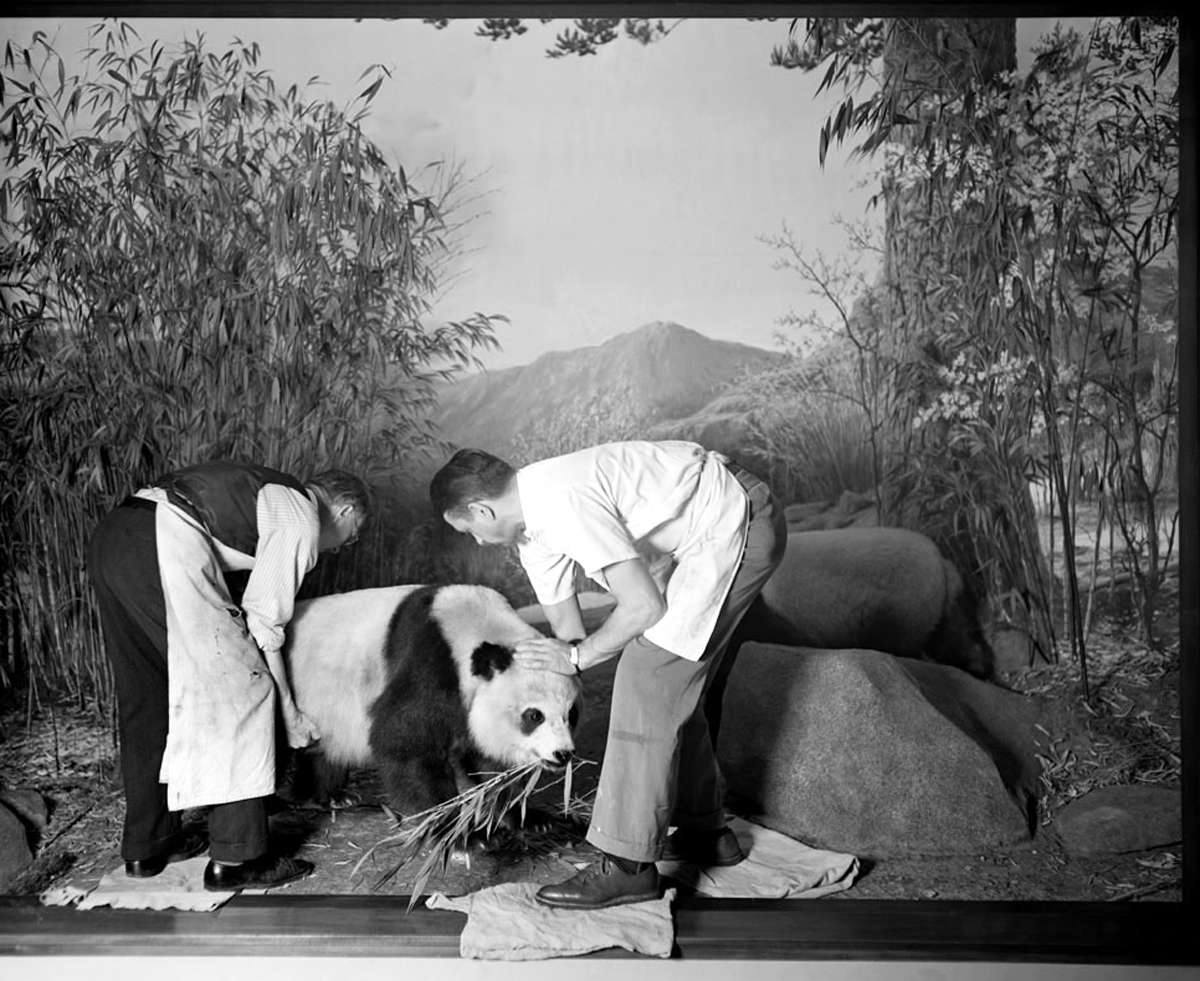

Ironically, although early dioramas depended on the use of hunted animals, they were born from the desire to protect the planet’s fauna and flora. Many of the major contributors — most notably Akeley and friend President Theodore Roosevelt — were hunters and ardent conservationists. They wholeheartedly believed if they could immerse museumgoers in the natural world, people would be more likely to protect it. Museums became staffed with teams of scientists, sculptors, taxidermists, carpenters, muralists and painters who made dioramas. The workers here were constructing the giant panda exhibit at the Field Museum, which was unveiled in 1931; the specimens were collected by Theodore Jr. and Kermit, two of Roosevelt’s sons.

Early diorama builders got up close to subjects

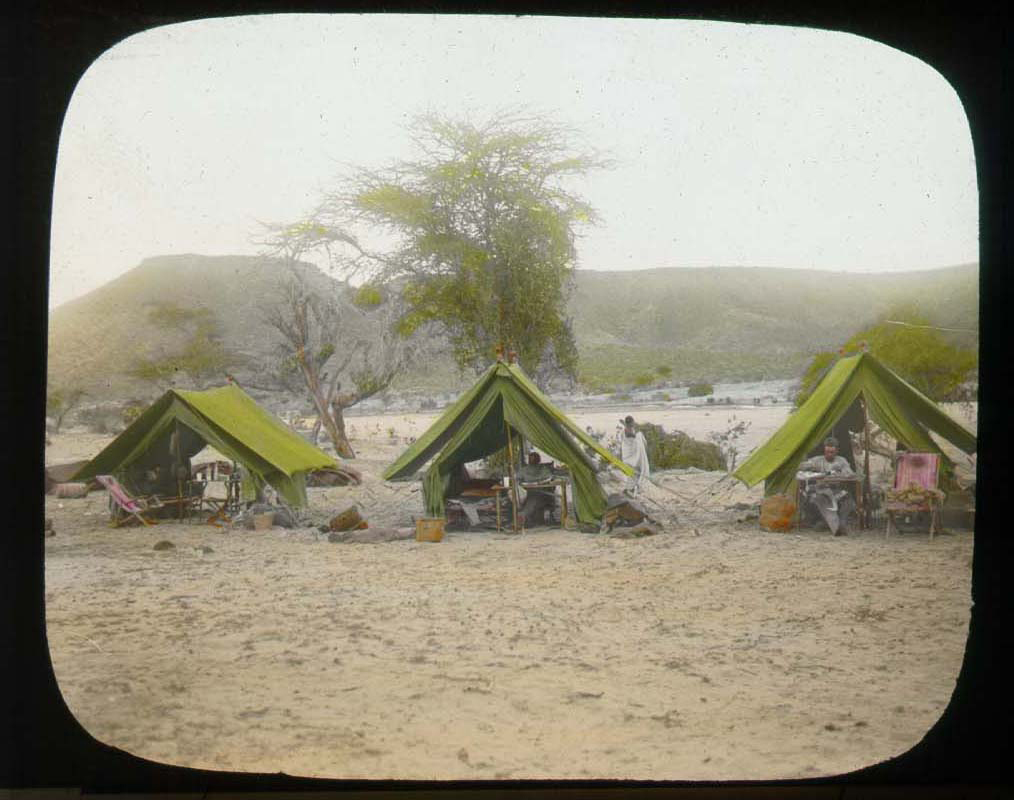

Back in the day, diorama creators like Akeley would go to the far-flung locations they’d later manufacture, in part to collect specimens but also to know their subjects and surroundings intimately. For instance, Akeley collected four striped hyenas in 1896 (this photo shows their camp in Somaliland). But the Field Museum didn’t build a display for them at the time, and the specimens had been placed in a bare case in the Hall of Reptiles. A 2015 crowdfunding campaign — led by Emily Graslie of The Brain Scoop, a YouTube series filmed at The Field Museum — raised $155,165 to create a suitable exhibit for them; Delehanty was thrilled to work on the team that built the diorama, the first at the museum in decades. “What made this project so exciting for me was that the taxidermist was Carl Akeley, the Carl Akeley, the father of the habitat diorama and the father of modern taxidermy,” he says.

While Delehanty doesn’t get to travel for work specifically, he steeps himself in research to provide verisimilitude in his dioramas. He looks at satellite imagery and videos, reads books and journal articles, and, most importantly, talks to scientists. “When I start a new diorama, I consult with botanists, zoologists, anthropologists and archaeologists,” he says. “Because of that, we can tell very complex stories.”

Start on a small scale

Work on the hyena diorama began with the team’s scrutinizing every resource available relating to Akeley’s trip to Africa, Delehanty says. They uncovered an expedition member’s journal, developed Akeley’s glass negatives, even consulted astronomy charts. The diorama team took note of everything — the size and shape of rocks in that area of Somalia; the color of the sand; the plants and animals that were found near the hyenas at that time. The team decided the exhibit would depict the morning of August 6, 1896, at 5:30 AM, at the exact GPS coordinates where the hyenas were collected. Before starting work in the museum hall, the team first made up a 1:10 scale model, and Delehanty painted a backdrop showing the stars that would have been visible that morning. “Even the moon is in the correct phase,” he says.

Get every detail right, down to the poop

It takes months to build a habitat diorama. “We scrutinized every single leaf, every single stone that went into it,” Delehanty says. He painted the backdrop with oil paint that he mixed with beeswax to reduce the sheen, which would make the exhibit look new and distractingly unrealistic. The team made rocks from chicken wire and plaster; replicas of aloe and Sansevieria trifasciata (called mother-in-law’s tongue for its sharp leaves) plants were constructed from neoprene, poured into plaster molds and then hand-painted. Every detail was checked with botanists and biologists. “I even had to remake the little ball of poo that the dung beetle was pushing around because a scientist said my first ball wasn’t fibrous enough for the environment,” Delehanty says.

The hyenas, which had been prepared and stuffed by Akeley a century ago, were X-rayed to see how they were put together. Conservators “refreshed” them by fixing tears in their skin and fading in their fur. In the past, taxidermists had used toxic chemicals such as arsenic in their work, which meant that all specimens had to be handled with extreme care.

The mission: Teach people to love rare animals

The feeling of having completed a diorama is euphoric, says Delehanty. When the full-sized diorama was unveiled to the public in January 2016 — the final mural was 17 feet high and 40 feet wide — he felt like a “proud father.” He says that someday his obituary might say, “Go to the Field Museum and see the diorama he made.”

Like his predecessors, he hopes the exhibit educates museumgoers about animals they’ll most likely never see in person — and makes them care about these creatures. While striped hyenas were plentiful in Asia and Africa at the time of Akeley’s expedition, there are now fewer than 10,000 adults in the wild, and they’re listed as “near-threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Conveying a complex culture without words

Delehanty also helped construct a Field Museum diorama showcasing the Hemudu, a Neolithic culture that lived in eastern China from 5500 BC to 3300 BC. The Hemudu were nomadic, moving during the flooding season, until they learned to build homes on stilts. For the Cyrus Tang Hall of China, Delehanty worked with archaeologists on this tableau that depicts a community near the Yangtze River. “The more I studied these people and their culture, [the more] I saw how central water was to their identity,” says Delehanty. “So I placed puddles randomly throughout the village and had people interacting with them. If you look [at the backdrop], there’s fog in the air. All these details collectively hit your subconscious and convey identity without words.”

He built the homes with floorboards made of popsicle sticks, spending hours hammering and scraping them, staining them with coffee, and speckling them with red paint to simulate blood stains because people usually went barefoot. Delehanty says, “I wanted the floorboards to tell a very complex story, as if they were worn down by generations of people.”

A must for a diorama creator: keen eyes

Now working at the Rochester Museum and Science Center in upstate New York, Delehanty is restoring old dioramas and crafting new ones — each with its own challenges. For a diorama depicting late summer in the tundra, he surrounded a caribou with hand-crafted tiles of mosses, lichen, berries and bushes — essentially creating pointillist pieces of artificial plant life. “I wanted it to be full of life, because it is,” he says. “People might think differently, but the tundra is one busy biome.” For a scene of fish in their winter hibernation, he drew inspiration from a pond near his home. “I remember laying down on a dock and examining the muddy, leaf-covered bottom and thinking, ‘That’s it!’ Observation is key, and that’s one of the best parts of doing what I do. ‘Knowing how to walk in nature’ is on my resume.”

The future of dioramas

“Currently, I’m on a team that is restoring a diorama from the 1940s of the city of Rochester as it was in 1838,” Delehanty says. “In 1838, the city was booming, and the Erie Canal [which is in the diorama] played a role in this. We are taking the diorama into the 21st century with new lighting, augmented reality and maybe a soundscape.” Visitors can see the artists at work as a “living exhibit” on display throughout summer 2017.

Many other institutions are also trying to figure out what to do with their old dioramas. Some are refurbishing them — Rochester officials were motivated by the upcoming 200th anniversary of the Erie Canal, to be celebrated in 2020 — while others are destroying them or moving them into less prominent places. Even though we now have Google Earth to give us detailed images of the world, YouTube to show us videos, and Instagram and Facebook to document our own encounters, Delehanty believes a diorama can offer a unique type of immersion. “That’s the goal of a great diorama, to make it feel like a real encounter with nature,” he says.