These incredible pups catch poachers, sniff out invasive plants and diseases, and more, thanks to the work of wildlife biologist and conservation-dog expert Megan Parker.

What happens to those dogs that are just too much dog for people to handle? “You know them — you go to your friend’s barbecue, their dog is so happy to see you that she pees on your feet, and she drops a slobbery ball in your lap,” says Megan Parker (TEDxJacksonHole talk: Dogs for Conservation), a wildlife biologist and dog expert based in Bozeman, Montana. “You throw it to get as much distance between you and the dog as possible, but she keeps coming back with the ball. By the 950th throw, you’re thinking, Why don’t they get rid of this dog?” All too often, their owners reach the same conclusion and leave their pet at a shelter.

Thanks to Parker and the team at Working Dogs for Conservation (WD4C), some of these dogs have found a new leash lease on life. They’re using their olfactory abilities and unstoppable drive in a wide variety of earth-friendly ways, working with human handlers to sniff out illegal poachers and smugglers, track endangered species, and spot destructive invasive plants and animals.

Parker first considered using dogs in conservation when she worked on the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone Park and was asked how researchers could track wolves through their scat, or droppings. “I started thinking how best to detect their scat off a large landscape, and the idea came up for dogs,” she says. In 2o00, she cofounded WD4C to train and use canines in conservation work. Most of their dogs are adopted from shelters or from organizations or work settings where they didn’t quite fit in.

While it’s fair to say almost all dogs love toys, wildlife-detection dogs are obsessed with them. “They’ll do anything to chase a ball or a tug toy,” says Parker. If their preferred plaything is thrown far into the brush or buried in a massive pile of leaves, no worries — they won’t stop looking until they find it. No food, obstacle or distraction can deter them, and WD4C staff have turned this single-minded focus into a powerful incentive. Their canine friends are rewarded with their favorite toy every time they locate a desired wildlife-related scent, which have included everything from elephant ivory and poachers’ guns in Zambia and trafficked snow leopards in Tajikistan to predatory Rosy wolf snails in Hawaii and invasive Argentine ants on California’s Santa Cruz Islands. The dogs are careful not to disturb or touch any specimens they pinpoint; it’s all about the toy.

Lily, a yellow Lab, is one of the group’s many sad-start-happy-ending stories. When the then-three-year-old came to the attention of WD4C trainers, she’d already bounced her way in and out of five different homes. She couldn’t sit still and she never, ever wanted to stop playing. Oh, and she was a bit of a whiner. Since joining WD4C in 2011, she has been trained to recognize a dozen different conservation-related scents and been deployed to track grizzly bears and sniff out the eggs, beetles and larvae of emerald ash borers, an insect that has killed millions of trees in the US and Canada.

The three-dozen-strong WD4C pack also includes purebred working dogs who weren’t right for their intended occupations. Orbee, a border collie, had the enthusiasm and live-wire energy required of ranch dogs, but there was one problem: he had zero interest in herding sheep. He also barked a lot. Since joining WD4C in 2009, Orbee has had a globe-trotting career — he has spotted invasive quagga and zebra mussels on boats in Alberta and Montana, monitored the habitats of the endangered San Joaquin kit fox in California, and assisted scientists in northern Africa in counting up Cross River gorillas, the world’s rarest gorilla.

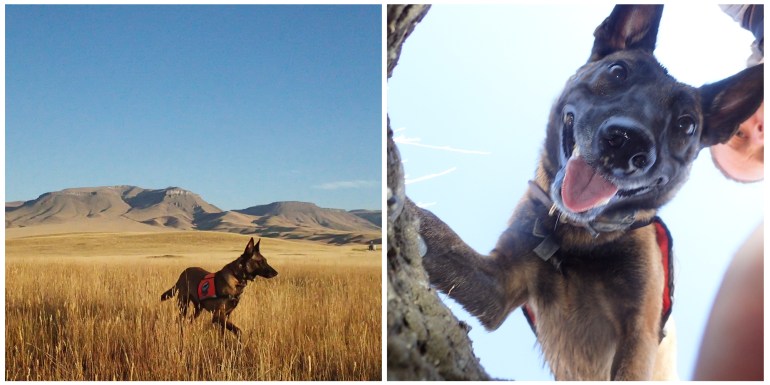

Jax is a Belgian malinois, a sturdy breed frequently used by the police and military. He was in training to serve with the US Army’s special unit, the Green Berets, until his handlers realized Jax doesn’t like to bite people — just toys. And, boy, does he loves toys; he’s even tried to climb trees to reach prized objects. Since 2017, Jax’s athleticism and high spirits have been used by the WD4C to perform tasks such as mapping the movements of bobcats in the western US.

“Different dogs have different strong suits,” says Parker. She and the WD4C team try to place their charges in environments that match their skillset, likes and dislikes. Unlike many dogs, Tule (above), a Belgian malinois who flunked out of a job with US Customs and Border Patrol, has absolutely no desire to chase small animals such as cats, squirrels and rabbits. This made her the perfect fit to help researchers monitor black-footed ferrets, which live in the same territory as a large, scampering prairie-dog population. The ferrets, once thought extinct in the US, were reintroduced in Wyoming in recent years. Tule alerts her handlers to the scent of live ferrets or their scat, information that allows state wildlife officials to map their distribution and see if the population is recovering. Without Tule and her pack, researchers would be forced to study the elusive creatures with cameras or live traps, undependable methods at best.

The dogs’ efforts have resulted in positive, substantial changes. The organization teamed up with the nonprofit Wildlife Conservation Society so their dogs could track the scat of four keystone carnivores (grizzly bears, black bears, mountain lions and wolves) through the Centennial Mountains in Idaho and Montana. Five years of doggie data showed that all four species depended on the mountains to move between the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem and central Idaho wilderness areas. Thanks to this information, activists were able to stop construction of a housing development that would have interrupted their migratory pathway.

Some dogs are searching for animals and plants that are most wanted for the opposite reason: they’re invasive species proliferating where they don’t belong and driving out native flora and fauna. There’s the previously mentioned zebra and quagga mussels, which spread by clinging to boats and watercraft, and which clog water and sewage pipes, foul up power plants, and destroy good algae. Tobias (above) is a specialist in finding them. In one test, WD4C dogs identified 100 percent of the boats with mussels aboard (human screeners spotted 75 percent). The dogs did the job more quickly, and they could also detect the mussels’ microscopic larvae.

Former shelter dog Seamus (shown at the top of the post), a border collie, is an expert in searching out dyer’s woad on Mount Sentinel in Montana. Humans have tried to eradicate the invasive weed by spotting its flowers and pulling out plants by hand, but these attempts barely made a dent. By the time it’s found, it’s often already seeded (and a single plant can produce up to 10,000 seeds). Seamus’s keen nose, along with those of three canine colleagues, learned to sniff out woad before it flowered, a time when it’s extremely hard for human eyes to see. They also found root remnants left in the ground. At a recent checkup, just 19 of the invasive plants were found on the mountain. “It will be a complete extermination,” says Parker. “It’s just going to take a long time because we don’t know how long their seeds last in the soil.”

The dogs’ hunting grounds even extend into the water. Although prized in their native habitat, brook trout are an invasive species elsewhere; in some places in the Western US, they are pushing out the native cutthroat trout. WD4C was brought to Montana by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Geological Survey and the Turner Endangered Species Fund to see whether their animals could learn to sniff out live fish in moving water. Reports Parker, “This project confirmed what we long suspected: that dogs can detect and discriminate scents in water.”

Pepin (above), who worked on the brook trout project, is part of an ambitious charge to train the dogs to detect infectious diseases in animals. “He’s done the first of a lot of things for us, because he’s so game,” says Parker. Some wildlife carry brucellosis, a bacterial disease that is particularly harmful to cattle. It’s difficult to tell when animals are first infected because they typically don’t display symptoms, so in areas where the disease is prevalent, ranchers tend to keep livestock and wildlife as far away from each other as possible — severely limiting the territory and movement of both kinds of animals. The hope is that dogs could provide a fast, reliable way to identify infected herds. So far, Pepin has shown he can discriminate infected elk scat with higher and lower concentrations of the bacteria, and W4DC is eager to explore this use of dog power. “We have proof of concept,” says Parker. “I’d like to move that work forward.”

There are so many other unexplored capacities and environments where dogs could help, Parker believes. To that end, WD4C started a program in 2015 called Rescues 2the Rescue, which aims to help shelters around the world identify would-be detection dogs and place them with wildlife and conservation organizations. What kind of dogs are they looking for? Ones that are, uh, crazy.

To clarify that adjective, we’ll close by telling you about Wicket, a black Lab mix who retired from WD4C in 2017 at the top of her game, having detected 32 different wildlife scents in 18 states and seven countries. Wicket languished in a Montana shelter for six months, barking up a storm and scaring away potential owners, until WD4C cofounder Aimee Hurt found her there in 2005. When she went to adopt her, the shelter director said, “You don’t want that dog — that dog’s crazy!” To which Hurt replied, “I think she might be the right kind of crazy.”

All photos courtesy of Working Dogs for Conservation.

Watch Megan Parker’s TEDxJacksonHole talk here: