What would you do if every photo you owned just disappeared? Would you panic? Cry? Would you feel like a part of you went missing? What if you lost your home or your hometown in the process too?

Our focus in the aftermath of natural disasters is on the immediate: the loss of life, of buildings and of infrastructure. But what about our memories?

After the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan — which occurred a decade ago on March 11, 2011 — Argentine photographer Alejandro Chaskielberg decided to explore these notions of loss and identity in Otsuchi: Future Memories, a collection consisting of portraits and found images of the community of Otsuchi.

Chaskielberg first found himself there a year and a half after the disaster, when the area was just beginning to recover. His Japanese curator, Ihiro Hayami, asked him if he would be interested in photographing a small town where some of Hayami’s relatives lived. Located in the Tōhoku region, the small fishing town had — according to the Japanese government — lost nearly 10 percent of its population to the tsunami.

From the outset, Chaskielberg was not interested in telling a straightforward story about devastation. “The challenge was,” he recalls, “what’s really the story that I’m going to tell?”

At first, he took only a handful of pictures. An image of car remains here, one of fishing supplies there, and many images of wrecked buildings. Soon after, he began to take portraits of survivors in those buildings — but specifically, the homes where they used to live. Accustomed to working in vivid color, his initial images of Otsuchi were black and white, for he felt “the scenes were so sad that they couldn’t have color.”

This all changed when, near the end of his trip, Chaskielberg stumbled upon a peculiar item. “I found a photo album,” he recounts. “It had been there for a year and a half without anyone picking it up. It was wet, heavy, and it smelled like a dead animal. It contained bubbles of color that leaked from the photos, and the colors blended with one another. I took a picture of it without giving it much thought and returned to Argentina.”

Many months later, he revisited the project with fresh eyes. “I saw those images again — but this time it looked like a painter’s palette. So, I took the photographs from that album to create my own and I used those colors created by the tsunami to color the images of the survivors.” With digital retouching, he tinted the images with his new custom colors. “All the colors you see in these images,” says the photographer, “were created by that force, by the tsunami.”

And, for Chaskielberg, “little by little, all the gray scenes started taking color. I used color as a bridge to connect the present and the past. As the link between their photos and mine.”

After coloring the first batch of images, Chaskielberg returned to Japan to find more photos. To his surprise, local NGOs and the Otsuchi government had a treasure trove for him: They had been recovering family photos that the tsunami had scattered all over the town, intending to send them back to their owners. “With the help and permission of the Otsuchi government, I had access to that impressive archive of thousands and thousands of destroyed photos. Contemplating those pictures, I realized the intangible damage that the survivors were facing. The damage to their memory and their identity — those blurred images were the expression of their loss.”

Chaskielberg also created a number of new images. For those, he used a long exposure (each of his original takes for Future Memories was exposed for around 10 minutes), a large format camera (“like the ones your great-grandparents may have had their pictures taken with”), and the moon’s light as the main source of illumination. He chose to shoot portraits of people in black and white, while landscapes were shot in color.

His final collection is an attempt to help heal the incredible loss experienced by the residents of Otsuchi. “When we lose a childhood photo or a picture of a loved one,” Chaskielberg says, “we feel like something is missing.” He adds: “Going back to our photos from the past is like opening the doors to a dimension where lots of memories we seem to forget, remain. Those images from the past — those cherished treasures — can help us propel ourselves into the future.”

Here are some of his selects from Future Memories:

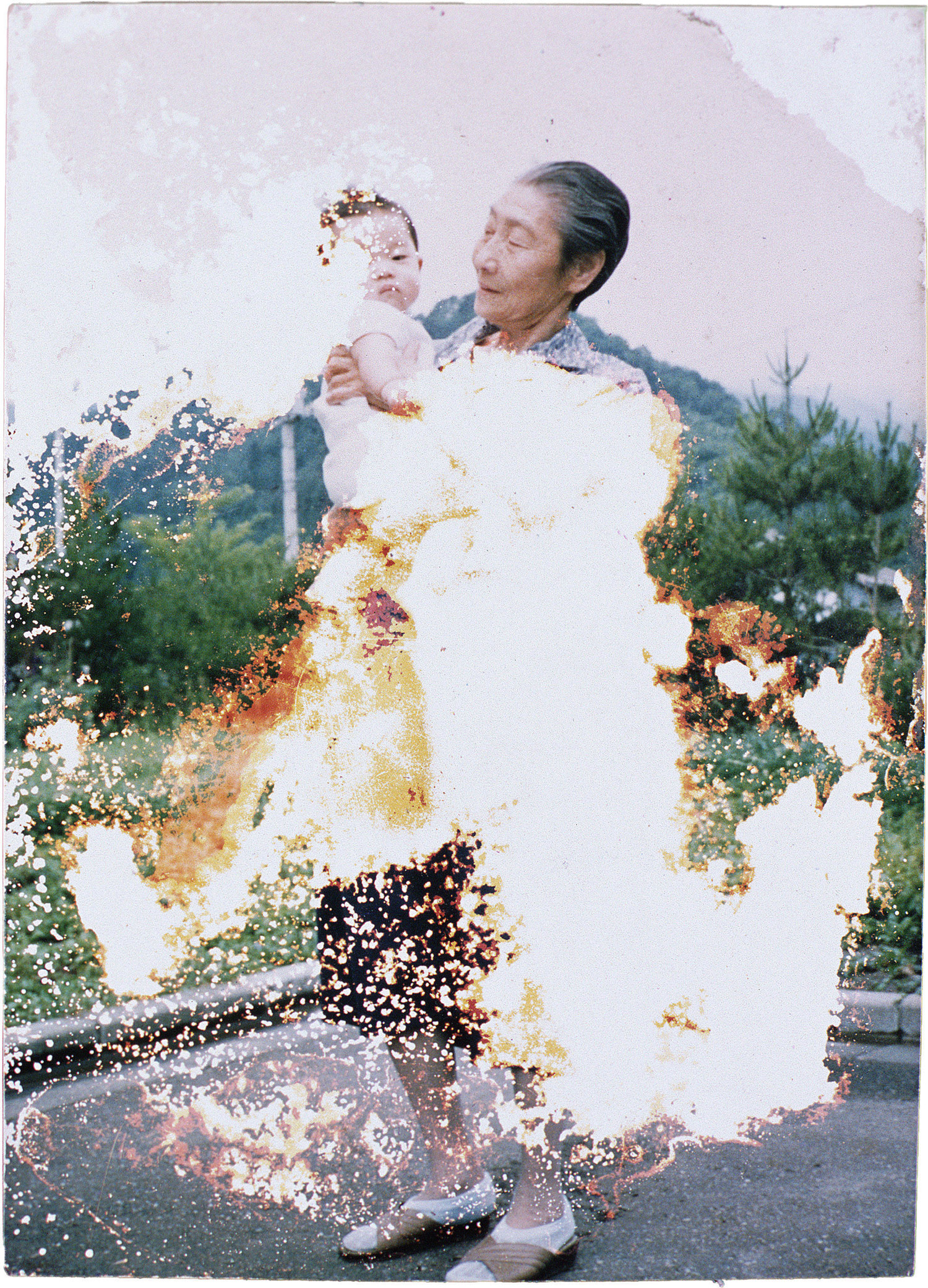

Recovered image of a grandmother with grandson

This found image could be “of a grandma with her grandson or a great grandma with a great grandson, we don’t know,” says Chaskielberg. “It interested me from the beginning because it looks like she’s surrounded by fire. These are the two generations at two extremes, and then there’s this fire or something that engulfs them, that was something completely random.” In the same way that the colors from a ruined photo album birthed a new palette, these damaged photos and the way they were damaged led to a new story to be born out of the wreckage.

Recovered image of a Japanese bride

“When brides get married,” says Chaskielberg, “they get photos done in studios with kimonos. This one was taken in a studio with a light and flash, all perfectly done.” Similar to the previous image, Chaskielberg was most intrigued by the way the photo was damaged. With this one, the bride was left floating in the air in that kaleidoscopic kimono, but with her face perfectly clear and intact. “I have the sensation that when someone cleaned this photo or it was dried, the movement that cleaned it was the one that erased the colors, too,” he adds.

“Floating house”

This family’s house was partially destroyed by the tsunami, and then subsequently consumed in a fire ignited from the post-tsunami debris. In the remaining foundation, the woman in the center posed with her son to her left, her brother to her right, and her husband in front.

After the tsunami, the family decided not to move into temporary housing; instead, they stayed in a small half-constructed house nearby (from where Chaskielberg took the photo). Their former house was at the base of a hill; when the tsunami came, the family climbed 66 feet, or 20 meters, up to the top and escaped to safety.

This was the first original photo that Chaskielberg took for the project, and he remembers feeling apprehensive as he began. “I felt so anxious for that situation, for those people that were in those destroyed places,” he says. It felt like “a spiritual moment.”

Because of the long exposure time, the people whom he photographed had to be completely silent and still for 10 minutes at a time — they had to sit with their trauma. But for some of his subjects, it gave them an opportunity to create something new from this raw and emotional place. Chaskielberg explains, “People could go to these places, where their history had been, and be together as a family, creating a new image.” Although this image was taken in black and white, Chaskielberg used the custom color palette he had made to digitally tint the image.

Two boys pose by the fallen tracks of the Sanriku Railway

“These two boys were introduced to me by a teen I had photographed,” the photographer says. Behind them, still standing in the Otuschi river, are the pillars that once held the Sanriku Railway railroad tracks and that were swept away by the tsunami. The boys told Chaskielberg about how before the disaster “they’d hang around the river, underneath the tracks. They’d go chat and play.” The rock-like piles they sit on for this portrait used to sit atop the pillars. The photo took them about two hours to create, using lanterns for lighting. Rebuilding after the tsunami, the government decided to leave the cube-like pieces where they’d fallen.

“Benten shrine”

The Benten Shrine is a sanctuary found on the small island of Hraoijima, which is accessible from Otuschi via a narrow walkway. Benten, also known as Benzaiten, is a Japanese deity worshipped by many — there are probably thousands of shrines to her scattered all across Japan, and this goddess is associated with literature and music, wealth, femininity and the sea. Even though Hraoijima was completely covered by water, miraculously the wooden shrine survived.

For Chaskielberg, this astonishing resilience spoke to him “of the power of faith.” In Japan, he says, sanctuaries are often placed in spaces where there are earthquakes or tsunamis, as protection. The red lighting that he used to illuminate the trees shines from another symbol of safety — a nearby lighthouse, from where he took the photo.

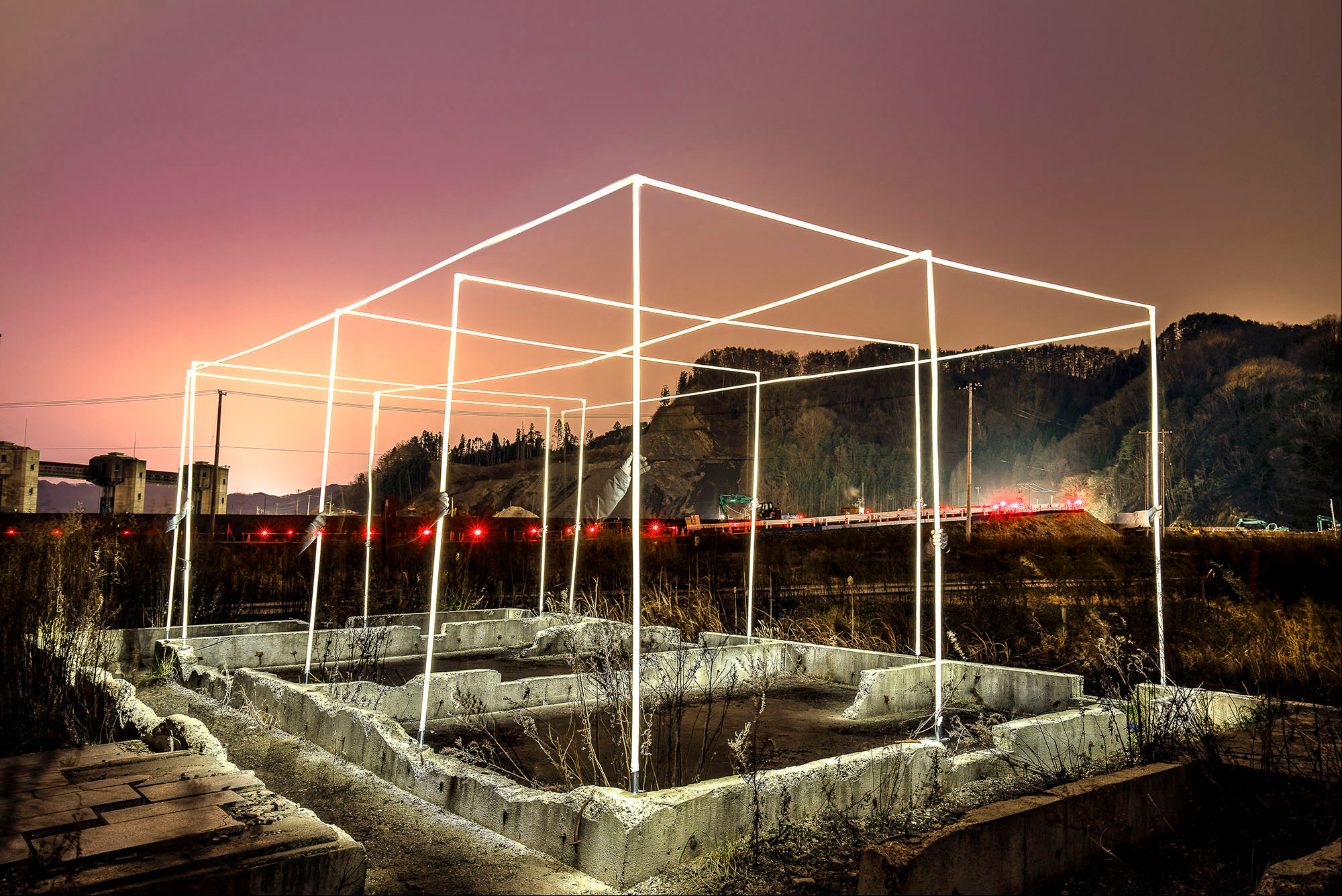

“House of light”

This image was the last that Chaskielberg shot for the project. Shot in color, it is especially important to Chaskielberg because his photography assistants, Mayumi Susuzki and Kazuhiko Chikaoka, made the image with him. You can see their hands holding up the light tubes that form the house’s shape. He met them when they took a photography class that he was teaching while he worked on Future Memories. They both lost their parents in the tsunami, “and they decided to work with photography because of it,” he says.

Chaskielberg and the pair obtained the materials for this image at the supermarket. He says, “I had this idea of constructing a house in the air with tubes of light, so we bought some PVC tubes and made a frame of the width of the house.” The day of the shoot, the temperature was 10 degrees below freezing. His assistants held up the rectangular frames, while Chaskielberg lit them with lanterns. Between takes, they all warmed up in his car.

Chaskielberg emphasized the importance of the visible hands in the photograph being his assistants’. As he puts it, “They are the ones who are reconstructing their history, they are reconstructing over destruction, and they are reconstructing with light. It’s not just anyone who is holding those tubes — it’s them.”

The themes of memory and identity explored in Future Memories are “photograpy’s function — the function of remembering and of generating our own identity,” says Chaskielberg. “We are, in a way, what we have lived and what our history is. And so how do we know that history? It’s in the images, the ones that take us to those places, to remember.”

All images: Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg. See more of his work at his website.

Watch his TEDxRiodelaPlata Talk (in Spanish) here: