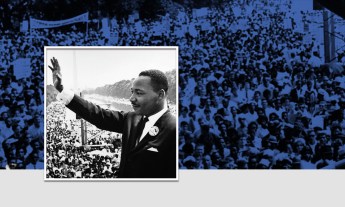

In Selma, director Ava DuVernay chronicles the 1965 marches that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. With Martin Luther King, played by David Oyelowo, front and center, the film has won plaudits, controversy, awards and, most recently, an Oscar nomination for Best Picture.

Alison Prato caught up with Ava to talk to her about her film and get her impressions of the man she’s been thinking about for so long; an edited version of their conversation, which took place in early 2015, follows.

What do you remember learning about Martin Luther King, Jr. in school?

I went to Catholic school in Southern California, so I learned the basics: “I have a dream;” he believed in peace, and he died, which I think are the broad strokes of what most people learned. I don’t think it’s much different from what you learn in schools about most events — very top line, a homogenized view of a radical mind. With Selma we were hoping to illuminate the nuance of his approach, his theory, his humanity. To take him down off that pedestal and break that marble open and really understand that he was an ordinary man who did great things. Most people see him as “Martin Luther King, Jr.” That’s not a real person, that’s a big idea that feels unattainable.

MLK’s a catch phrase: “I have a dream.” He’s been reduced to four words.

David Oyelowo has said that he doesn’t love that MLK has become a day, and that he was proud that the film made him back into a man.

Beautiful. We’ve said this quite a bit: He’s a holiday, he’s a stamp, he’s a street name in black neighborhoods, he’s an elementary school in some parts of the city, he’s a catch phrase: “I have a dream.” He’s been reduced to four words. People don’t even know his regular speaking voice, they only know his speech voice. They don’t know what he sounded like in normal conversations, or that he had four kids, or that he died at age 39, or that he had no intention of being an activist in this way. He was a regular preacher from Atlanta who got swept up in this movement when he moved to Alabama. So yeah, David said it exactly right. And that was our goal every single minute of every single day, with every single frame, every single line in the script: To try to portray him as an ordinary man who did great things. It was about adorning him with all of the beauty of that movement and not letting it just sit with him, which is another disservice to his legacy, and something that he would’ve hated.

Why would he have hated that?

He was always deflecting the light from himself, always trying to be inclusive of the movement, always calling out his friends in speeches, always saying, “I am one of many.” And so the fact that he’s come to represent a whole movement was in many ways a negation of other key leaders of that time, especially those around him. It’s something he would not have liked, and yet it happened. And so that was one of the first orders of business when I came on board the project: to open up the scope of the picture, from just a mano a mano between King and [President Lyndon B.] Johnson to what Selma really is about — the power of the people.

The fact that MLK has come to represent a whole movement was in so many ways a negation of other key leaders of that time

Free screenings of Selma are being offered to thousands of school kids around the country. How did that come about?

This whole movement happened quite organically from black business leaders, headed by this man, Charles Phillips, in New York. He saw the film and said, “Gosh, we have to do something.” So he started calling his friends, and those friends called more friends, and a few days before the movie opened wide, they were offering free tickets to 7th, 8th and 9th graders. They ended up having 75,000 requests from kids on the website. They honored them, and then it just kind of spread to a bunch of other cities. It’s the most moving thing that’s happened. In a week of Golden Globes and dresses and reviews and all of that, it’s been the most lovely part of a really lovely experience overall.

I love how on The Daily Show, Jon Stewart asked you, “How does it feel to present a movie like this now that racism is over?”

[Laughs.] Yeah.

In all seriousness, when it comes to Ferguson and Eric Garner and Black Lives Matter, how far have we come — and how far do you feel we still have to go?

This stuff takes time. There’s been a maturity and a blossoming that we all can clearly say we benefit from each and every day. But there are systemic issues that have also blossomed and matured, and the challenge is for freedom fighters and people who believe in justice and dignity to continue to push against those. So yes, laws were passed that allow us all to sit in restaurants with one another and that allow me to be able to vote. I mean, can you imagine? I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to sit on a jury, or to determine who governs me? It’s a jawdropper, it’s amazing, it’s absurd, and it’s in our recent living memory — just 50 years ago.

I’m really bolstered by this time, where these tragedies have really ignited a sense of action.

So to say nothing has changed is to be disingenuous about what really was happening at that time. In so many places it was state sanctioned terrorism, and that is no longer happening in the pervasive way that it was. But there are still systems and institutions in which policies are blossoming and maturing that are not for the good of the people, and so the people have to do the work. I’m really bolstered by this time, where these tragedies have really ignited a sense of action. It’s something I haven’t seen in my adult lifetime and my hope is that it can move beyond being a moment to a movement. And I believe it can.

You used Twitter to make a few statements about the portrayal of Lyndon B Johnson in the movie, which some have taken issue with. For example, “LBJ’s stall on voting in favor of War on Poverty isn’t fantasy made up for a film,” and, “Bottom line is folks should interrogate history. Don’t take my word for it or LBJ rep’s word for it. Let it come alive for yourself.” How has social media played a role in your moviemaking and in communicating with moviegoers and the world?

It’s a part of my process. I do not see Twitter as an extra burden thing I have to do. It’s like stepping into a room and listening to what people are saying. I’m walking around this house, which is my day, and at some part of my day I go into that room and listen to what’s going on, or I jump in for a second and then I step out. I think it’s powerful, I think it’s connective. If you see Twitter as something you have to do for branding, or something you have to do because people tell you you have to do it to promote a film, that’s a certain energy you’re bringing. For me, it sits with my whole idea of films being a collaboration, not only with my fellow craftsmen on the film, but the audience. Then when it comes to something where I need to speak my mind, or I need to set the record straight, I’m able to do that without having to go through other channels.

You should know about those, having once been a publicist.

Yes, I was one of those channels for a long time, and every time you go through a channel, you lose your message a little bit more. I think Twitter is an amazing tool for people to have their voices directly heard. And I saw the power of that, especially around the opinions of some people regarding aspects of our film.

The random idiot doesn’t deter me.

Isn’t the negative side of social media unavoidable?

Twitter has this great thing called “blocking,” and I use it very often [laughs]. I don’t let that stuff get into my bloodstream. There are nasty, nasty things on there, but gosh, there are 100 times more bits of beauty, 100 times more bits of information, 100 times more bits of illumination. The random idiot doesn’t deter me from being able to get on and treat it as a news feed, or treat it as a conversation, or treat it as a platform to get my voice heard.

TED recently published a talk by the diversity advocate, Vernā Myers: How to overcome our biases and walk boldly toward them. Did you discover any biases within yourself that you maybe didn’t even realize you had until you started exploring this subject matter?

I mean, we all have them. That’s just a fact. Someone says they’re color blind, they are actually blind to their own humanity, you know? Unless you’ve evolved to the status of saint, unless you’re actually physically blind, the society that we live in doesn’t allow us not to engage with one another within certain ideas about what that other is. We might be liberal progressive people, but we exist in a society that has systems and a history that’s not liberal and progressive. And so we have been stained by that in some way, and our job as progressive people is to continually challenge ourselves on those things. Just because you have those biases and those prejudices and those assumptions about people doesn’t mean you’re that person. The question is, “Are you challenging them within yourselves?” That’s our job at every turn. It’s hard. It’s a constant struggle, but I see a lot of people doing it; I certainly try to do it. Sometimes we fail, and we do better the next time.

Featured image of David Oyelowo in Selma courtesy of Paramount Pictures.