Millions of women singlehandedly raise their children in the war-torn country, but their stories are rarely told in the media. Photographer Kiana Hayeri captures their struggles and strength in these photos.

Malika is 28 years old. Just 14 when she was married off by her family, she lives with her five children in a small room in the Wazir Abad neighbourhood in Kabul, Afghanistan. Malika is also a single mother — when she was eight months pregnant with her fifth child, her husband was murdered, and she now supports her family on a monthly income of 800 afs, or $12, from washing clothes. The hardest part of being a single mother, Malika says, is watching her children go to bed hungry.

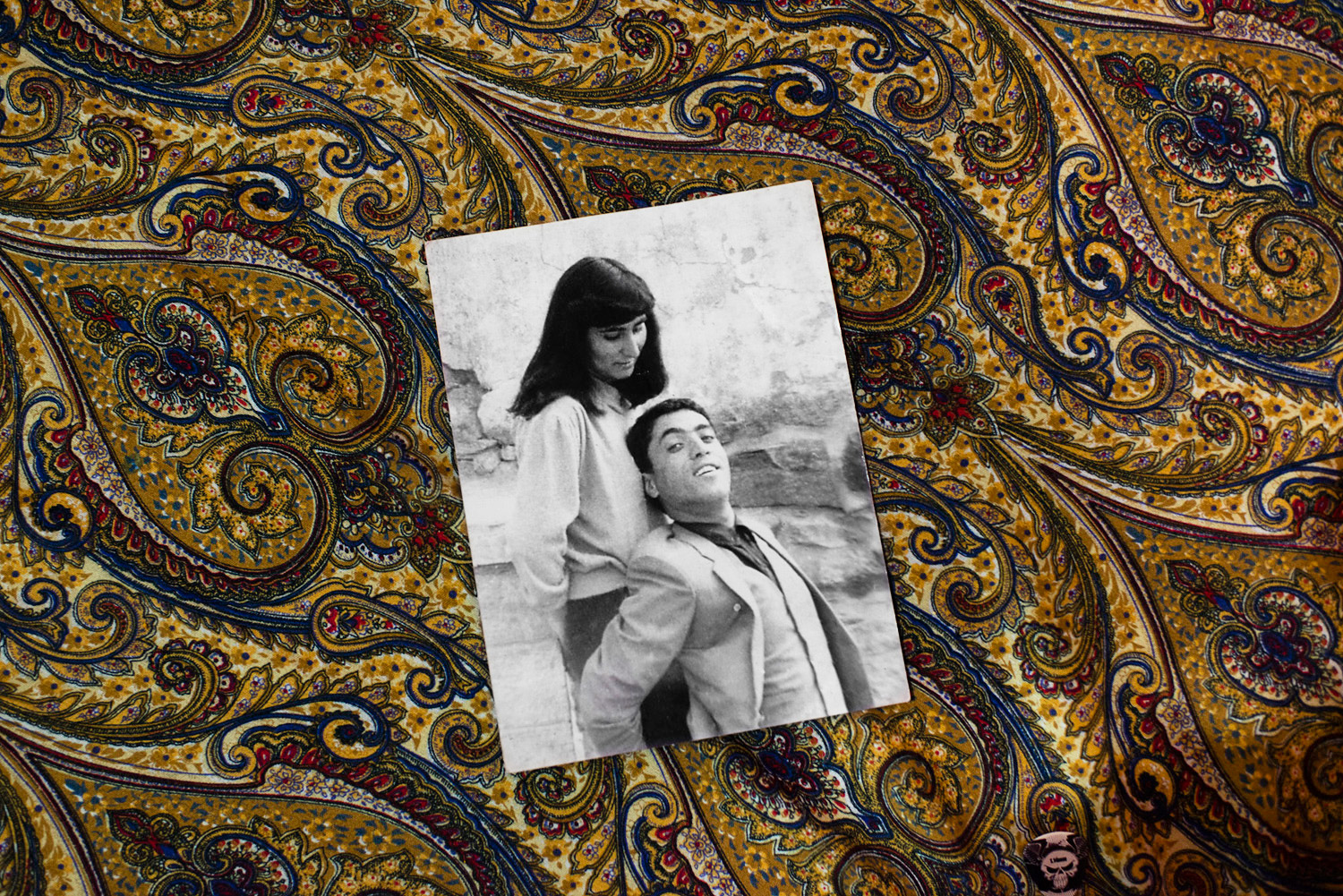

Photographer Kiana Hayeri, a TED Fellow based in Tehran, Iran, was the same age as Malika when she spent one month last summer photographing the intimate and scarcely seen daily lives of around 30 single mothers in Kabul and at a women’s prison in Herat. “When you ask somebody outside of Afghanistan what they picture when they think of the country, everyone talks about war, land mines, men with beards,” says Hayeri. “But never mothers, and especially single mothers.”

Culturally, women in Afghanistan are expected to be modest, which means most are reluctant to be photographed. But Hayeri believes that because the mothers in her images did not have husbands, they were more willing to welcome her into their homes and tell her their stories. “A lot of these women are very lonely, so for them, it was nice to talk about everything and vent out their frustrations at the difficult parts of life,” she says.

Hayeri, a TED Fellow, has an eye for under-the-radar stories like these — stories of everyday life from places around the world known to most outsiders for their civil strife or extreme violence. She has photographed queer teenagers in her home country of Iran, ex-child soldiers learning capoeira in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Syrian refugees seeking asylum in South Africa.

Nearly four decades of war, terror and internal conflict in Afghanistan have left Malika and millions of mothers like her without husbands. Yet there is no word for “single mothers” in Dari and Pashto, the languages spoken in Afghanistan. “Single moms are described only by the status of their husbands,” Hayeri says, “so they’re either widowed or divorced. But their motherhood is not recognized.”

Although more Afghan women in urban areas have started going to school and getting jobs in recent years, 85 percent of women in the country are still illiterate and only 20 percent are employed. “Women really don’t have lives outside of their homes,” Hayeri says. When a woman’s husband dies, she is often forced by family to marry a brother-in-law, usually as his second or third wife, so she will have a man who can take care of her family. But what happens to those who don’t remarry? “Unfortunately, in Afghanistan, and even in Kabul, a woman without a man in the house is considered immoral or available,” Hayeri says. “Single mothers endure serious harassment, abuse and threats, usually coming from neighbors and shop owners.”

Most of the single mothers Hayeri met were either unemployed or barely able to provide for their families with jobs cleaning homes and washing clothes for the wealthy. When one women she photographed, Mina, was pregnant with her fifth child, she was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis and became paralyzed from the waist down while giving birth; the child did not survive. Her husband kicked her and their children out of the house, and he re-married. Jobless, Mina has attempted suicide multiple times and told Hayeri she resented her own daughter for saving her life.

Afghan single mothers receive very few social services from their government, and media coverage of the ongoing war as well as international aid for women have both declined in recent years. Only a small fraction of the single mothers that Hayeri met have defied the odds and found success. Aziza, 52, for example, has a good job at the National TV and Radio of Afghanistan. She lost her husband to cancer in 2006 and has brought up her four children on her own with the support of her brother-in-law, a prominent musician.

Unsurprisingly, the children of single mothers in Afghanistan are forced to grow up very quickly, and their lives are stressful and their opportunities constrained. Often, the oldest daughter will be forced to leave school to assist their mother. “The daughter of one woman I met, Shakar, was very resentful and bitter to her mother, because she made the decision not to pull out the oldest son from school, but to pull her out instead,” Hayeri says.

After speaking to so many single mothers and observing them and their families, Hayeri believes that education is key to changing their fates. Ensuring that young women remain in school will help a new generation of women enter the workforce and achieve greater independence and better jobs. And while not all educated Afghan women are able to find employment, they tend to allow their children more freedom and let them stay in school for as long as possible.

Of course, the culture cannot change if the men don’t too, acknowledges Hayeri. A staggering 87 percent of women in Afghanistan have reported experiencing physical, sexual or psychological violence, and most of the men Hayeri met showed little respect for women’s rights. She did, however, observe that the sons of single mothers exhibited a deeper appreciation for the role women play in Afghan society. “All of the men I met who were brought up by single moms have more respect for women, for their wives, even for their own mothers,” she says. “If women can teach their sons to have respect and value for their wives and their sisters and their mothers, the next generation will be a little bit better.”

Hayeri’s photos, which were published in Harper’s Magazine in May, won her the International Academic Forum’s grand prize in documentary photography earlier this year. But she says that most of the single mothers haven’t seen their published photographs yet — and probably won’t, because they lack access to smartphones or the Internet. Hayeri recalls many of her subjects asking how their lives would change after she took their photographs. She remembers telling them, “I honestly don’t know. But I think sharing your story will touch some people, so hopefully in the bigger picture it will make changes.”

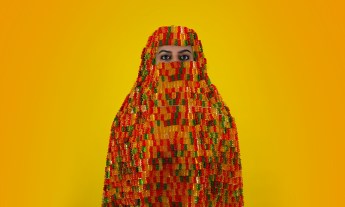

What’s next for Hayeri? She is working on a project that profiles women in Afghanistan as agents of change, as opposed to victims of circumstances. Her subjects include a successful TV host of the first women-focused station in the country, women in the police force and military, and a judge who works on child abuse cases. “At a time when international interest in Afghanistan is diminishing, it’s crucial to illustrate the progress that Afghanistan has made in the past 15 years,” Hayeri says. “It is important to show there are still people thriving inside the country — especially a younger generation that has seen nothing but war — whose lives could drastically change if they just have the opportunity to change them.”

All photos from Kiana Hayeri.