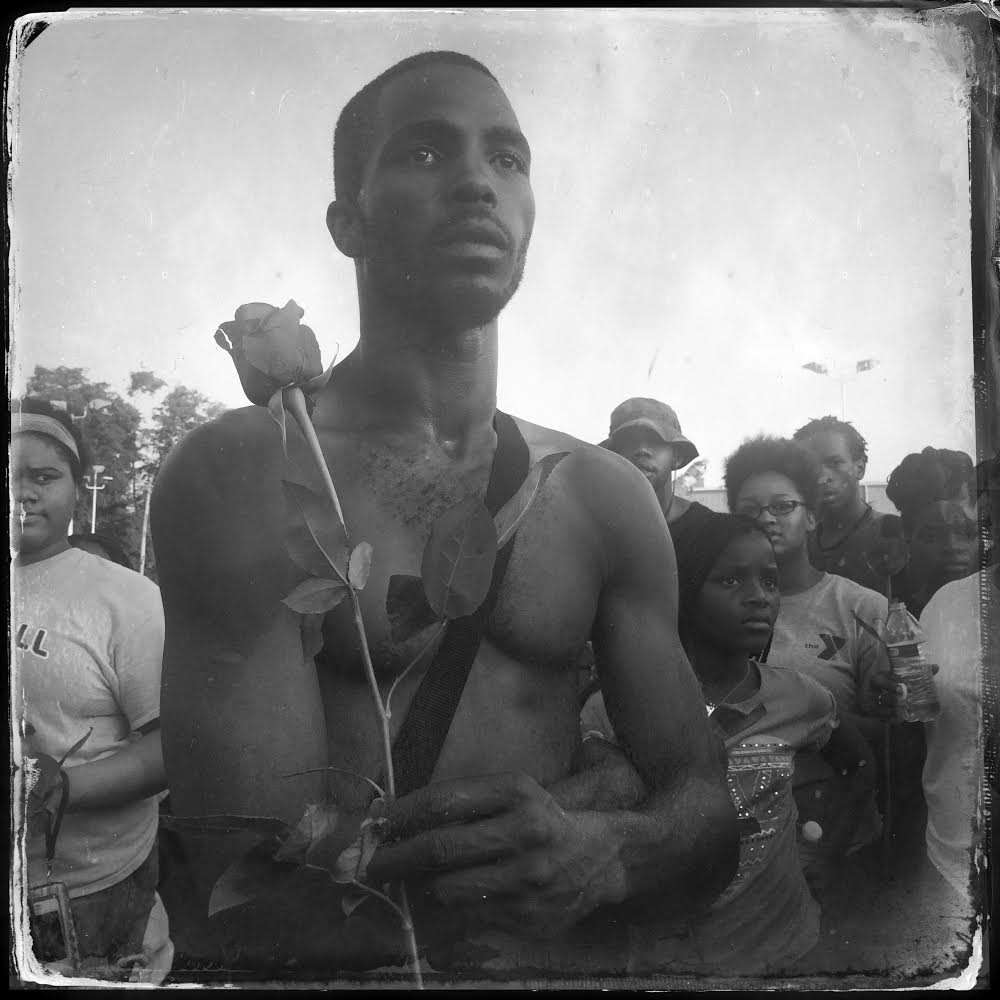

In Ferguson, Missouri, a grand jury will soon decide whether to indict police officer Darren Wilson for killing an unarmed teenager in August. Photojournalist Jon Lowenstein talks about what happened.

Soon after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, photojournalist (and TED Fellow) Jon Lowenstein traveled to Ferguson, Missouri, on assignment with TIME magazine to document the effect that the young man’s death had on the town. During those first volatile days and nights in Ferguson, Lowenstein also made a short film — commissioned by the UK’s Channel 4 — that starkly depicts the anger, tension and power disparities he saw there. (Watch the film here.) Both police violence and and citizen protests have continued in the months since, and in St. Louis in October, another teenager was killed by another officer. We asked Lowenstein to tell us about his personal experience of Ferguson’s civil unrest.

You do a lot of work documenting poverty, violence and racial tension in Chicago and elsewhere, and you’ve seen a lot of police violence against people in poor communities. Yet Ferguson hit the world media in a way that most of your subjects have not. Why do you think this story in particular has drawn so much attention?

This issue has been brewing for many, many years. I think the killings of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and many other people over the last few years set the stage for the anger over Michael Brown’s shooting and the disproportionate use of police force in response to the subsequent protests. This kind of state power has been carried out against individuals in poor communities throughout the U.S. — but it seems Ferguson finally woke up people outside of those communities, not just in the U.S. but outside it, to what’s been going on.

It wasn’t just that Brown was unarmed, but that the police response was so disproportionate. Darren Wilson clearly made a mistake, and the police in Ferguson stood behind him 110%. If you compare it to the Eric Garner case, there was immediately admission that the chokehold was illegally used.

From what you observed on the ground, did you get the impression that, had Ferguson police apologized right away, things would have gone differently? Or was tension already so high that it would have happened anyway?

I think what got people really upset was the intense, militaristic response. They were drawing down on people in military garb with fully loaded weapons. But in general, the levels of social violence within the overall community of Ferguson are not high. There’s more in nearby St. Louis, where Vonderrit Deondre Myers, another young man, was recently killed by an off-duty police officer. So it started with Ferguson, and then it grew. People from other communities came in. Young people came out and took over the street. There was some looting, but the majority of the people just wanted to protest peacefully. On the first Thursday night that I arrived, people were cruising up and down W. Florissant, along with thousands of people protesting. Later that night is when the tear gas started.

It was a real mix of emotions for people. On the one hand, there was a release of a real sense of repression and anger directed at the reality that, out of the 53 police officers there, three weren’t white — as well as anger at the very punitive court system that exacts high court costs on mostly poor people. All these little things add up over time.

What was the makeup of the crowd in the streets, racially speaking?

It was mixed, but it was definitely more black folks overall. But they were from all over the whole St. Louis area, and then people from other communities all over the country started to arrive. This led to a kind of conversation on the street about whose voice was being heard, and the best way to protest.

At first it was young people who were protesting in a very confrontational way. “We want change; we want justice for Mike Brown.” When the police responded with a show of force, it became a head-to-head situation. Interestingly, there was very little political ideology in the message at first — it was just a pure moment of reaction and rage, of truly honest dissent. So the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” response was a very strong way to be in the face of the police, in the face of the guns. Then came a wave of preachers and older community leaders, who organized in Ferguson to try to keep the peace and, in some ways, to tamp down the more forceful and confrontational message being put forth by the young folks.

Then came outsiders from Chicago, New York, and different areas of the country — and these people did have a more defined political ideology: “It’s not just about ‘Mike Brown’, but they’re about all of the people who’ve been shot by police,” and so on. By the time they arrived and were doing that, some members of the community were saying, “No, we don’t need more direct confrontation. We don’t want that confrontation with police, and we’re the ones who have to deal with that once you leave and go back to wherever you’re from.” Or, “You are here as an outsider, and you’re not really respecting where we are at, at this point in the protest.”

How did this show up in the film?

The three forces at work in the film were the protestors, the police and the media. At first it was protestors versus police. Yet, as the media grew in numbers, they became their own force within the whole story. That’s why I included how the police were attempting to manage the media. The police were not always restrained with the photographers and journalists. They arrested several journalists and also hit some photographers. And the protestors understood the need for us to be there. It was a really interesting moment in America — in American history, I would say.

Today, this issue is not going away. Just recently a 17-year-old was shot and killed by a member of the Chicago Police Department. Unlike Mike Brown, he was armed with a knife. It’s reported that none of the officers present had a taser. Either way the young man is dead and we, as a country will have to deal with that sad reality. How we choose to deal with this issue will help define who we are individually and as a nation.

[vimeo 104197761 w=500 h=281]

You can also follow Jon on Instagram: @jonlowenstein.