When Jane Chen and her team arrived in India in 2008, it was with a bold idea. They wanted to develop a simple, affordable solution to a terrible problem: infant mortality.

They went to the right place. According to a recent Child Mortality report, produced by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, India accounts for more than a quarter of neonatal deaths worldwide, about 725,000 babies in 2012 alone.

Infant mortality is the result of many factors; Chen and her team decided to focus on the fact that many premature and low birth weight infants are especially vulnerable to hypothermia, and they came up with a design to address this problem. Embrace is a sleeping bag-style baby warmer that can be used when high-tech, hospital-based incubators are not available to mothers who either can’t afford to pay for a hospital stay or who can’t afford to remain away from home (and work) for long periods of time. In contrast, Embrace is portable, affordable and low-tech.

“My team and I realized there was a need for a low-cost, locally appropriate solution to this problem,” Chen said in a talk in early December 2013 at TEDWomen in San Francisco. “It had to be extremely easy and intuitive to use and able to function without a constant supply of electricity.”

But, for all they thought the idea was a good one, the Embrace team knew there’d be no substitute for observing target users on the ground and in the field. “There are so many nuances that are critical to design and effective implementation, so many nuances that you don’t understand unless you’re there and living and breathing that culture every day,” Chen, a TED Fellow, said in a recent telephone call. Appreciating this critical part of the development process prompted her to leave San Francisco in 2009 to live and work in India full-time. The first demo of the warmer was a success, garnering acclaim, news stories and even a TED Talk — but she knew this was just a beginning. That original design was made for local health workers. What about making it useful for moms directly?

The hunch was backed up by product tests, which showed that mothers, even those who are illiterate, did even better at using the Embrace warmer than their local health care workers. Which makes sense, says Chen: “Who fights harder than a mom for their child?”

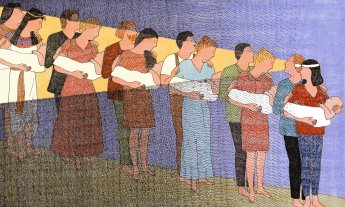

So Chen and her team went to India to listen to the direct feedback of the mothers who’d actually use the product. Not the nominal nod at a focus group of so many design programs, this was an exhaustive, intense process, with mothers having a say over everything from the straps on the baby warmer to the instructions printed on its front. “Mothers would say, ‘We don’t trust western medicine. If you told me to give a certain dosage of medicine to my baby, I’d cut it in half, because it’s probably too strong. If you told me to keep the baby warmer at 98 degrees, I’d keep it at less than that, because it’s probably too warm,'” Chen recalled. The new Embrace solution: remove any chance of unintended user error. For instance, by swapping out the numerical thermometer for a simple red/green light. The Embrace warmer is either warmed to the correct temperature to use or not.

Chen’s team also designed the product to complement practices like skin-to-skin care, or putting a baby on a mother’s bare chest. This is an extremely effective form of thermal regulation that provides other benefits to the child — but it can be difficult for mothers to provide this type of care continuously throughout the day. As such, the team designed the product to allow for easy access to the baby, so mothers could provide skin to skin care and breastfeed when possible.

As with any design, the product itself is just one part of the story. Spending time in the homes of their target users also uncovered the social and cultural conditions at work around the arrival of a new baby. “Oftentimes the mother-in-law is the decision maker,” Chen said. “So we needed to figure out how to involve her too, whether by having her heat the water or replacing the wax pouches. Really, the biggest question is how you think about the system as a whole, not just from a technology perspective but from a usability perspective, and that requires understanding the social dynamics of systems.”

Creating a system to distribute baby warmers to those who need them has also been a complex, lengthy process. So too developing a business model that would allow the company to grow while still reaching women who often rank among the poorest in the world. That’s why Embrace now has both a nonprofit arm, which donates the product to those in need and runs educational programs, and a for-profit side, which sells the baby warmers to government entities and private clinics. It’s a two-pronged approach Chen hopes can meaningfully combine reach and scale.

Embrace the company won’t remain devoted only to baby warmers; plans are under way to develop products or services that might tackle some of those other factors that cause infant mortality, perhaps diseases such as meningitis or pneumonia or infections such as sepsis or diarrhea. “Embrace really goes beyond the baby warmer,” says Chen, who recently moved back to San Francisco to work on developing strategic partnerships, confident that the team in India is set up to enjoy success rolling out the company’s first product — and that they’ll continue their research with mothers. “We’re back on the ground working to understand where the gaps in the market are — and where else we might meaningfully help through human-centered design.”