In these bold, black-and-white images, unrecognized people from many countries get a chance to be seen, thanks to the work of French photographer and artist JR.

In 2004, French artist JR found an abandoned camera on the Paris metro. Ever since, he’s been taking black-and-white portraits of people and pasting these oversized images on walls, scaffolds, rooftops and other surfaces around the world. In Paris, his images have humanized young people living in the projects; in the Middle East, his display stressed the commonality between Israelis and Palestinians; and in cities like Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Kibera, Kenya, his floating eyes celebrated the incredible strength of women. JR sees portraits as transformative for the person pictured. “They are a way to say, ‘I exist,” he explains, but they are bigger than that. They serve as a reminder of the inherent dignity of every individual and can safeguard against the instinct to distance and dehumanize.

As the winner of the 2011 TED Prize, JR decided to share his methods with the world through a project called INSIDE OUT. He invited anyone, anywhere, to take portraits in their community and with a social message in mind. His studio then prints them up as large-scale posters and mails them back to be displayed in a public space. More than 300,000 posters have now gone up in 140 countries, and a new book, JR: Inside Out, has just been published that celebrates the breadth and impact of these actions. “Six years later, I am still amazed every day by the creative power of participants,” says JR.

Witnessing a revolution

Shortly after JR launched INSIDE OUT from the TED stage, he traveled to Tunis, Tunisia, to be part of the first action. It was during the Arab Spring, and a group of local organizers wanted to paste over images of deposed president Zine el Abidine Ben Ali with images of everyday citizens. They called their action, “Artocracy in Tunisia,” and 15 photographers, including Aziz Tnani, captured 600 images for it. “When JR came to meet us with the first rolls of pictures, the sensation was amazing,” says Tnani. “I felt proud to be part of the project and to give this image of hope and democracy.”

The action didn’t go quite as planned, however. People were suspicious of the new images, and some were pulled down. “Tunisians had just managed to take down the president’s pictures, and they saw this as someone trying to impose new pictures on them,” says Tnani. But the organizers soon saw something hopeful. “If, at first, we took it for a demonstration of hostility,” says JR, “we soon felt that it was the expression of a new freedom, the right to say ‘no.’”

One image from the action became iconic. Inside a police station that was burned during a protest, Tnani pasted a photo of a man he’d met in the city of Kairouan. Littered all around the image were the ID cards of people who had been tracked by the authorities. “I was proud that this portrait overlooked that, as if Tunisians were discovering all these hidden files,” said Tnani. “It made me feel a part of the change.”

Visibility for garment workers

On April 23, 2013, cracks appeared in the walls of Rana Plaza, a massive complex that housed five garment factories in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The next day, the building collapsed in the world’s deadliest garment-factory accident and 1,134 workers were killed. Most of them were women, who had been making clothing to supply international chain stores like Primark and Benetton. Journalist Jason Motlagh and producer Susie Taylor set out to investigate, creating a powerful interactive story for VQR magazine. But they wanted to do more. “Imagine meeting women who were losing sisters and children because fast-fashion trends in the United States and Europe were stoking unprecedented demands,” says Taylor. “When we landed in Dhaka, there were three to four factory fires a week.”

They teamed up with local photographers to take portraits of garment workers, and in May 2013, they installed their INSIDE OUT images in the Korail slum. “We wanted workers in the garment industry to know that we cared,” says Taylor. “So when they came out, I welled up.” The attention was meaningful for the workers — and it also led to action. “In the months after, various trade associations stepped up alongside President Obama to call out unsafe work practices in the name of those who had died,” says Taylor. “The unions in Bangladesh were given a real fighting chance to support workers, and new building codes were put in place.”

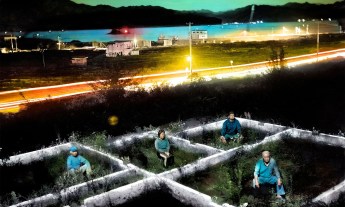

Guardians of the stone

The word “artist” evokes images of da Vinci, Picasso, O’Keefe — icons whose work are part of the canon. But with an INSIDE OUT action in 2014, production manager Odette van Rensburg and photographer Eric Gauss wanted to celebrate a group of artists who rarely got acclaim: Zimbabwe’s stone sculptors. They create beautiful work, yet face tremendous economic hardship. They photographed stone sculptors of all ages from the village of Tengenenge, then posted their portraits in a rock quarry in the capital, Harare. “Having spent time with them, I felt that — in front of a block of stone — they just light up. So that’s where I wanted to paste,” says van Rensburg.

To see this installation, people had to travel to a place they wouldn’t normally go, traversing the steep quarry paths. So van Rensburg was thrilled to see so many people flock there, especially school groups. “People had to smell and feel the stone,” she says. “I hope it encouraged them to spend time with the sculptors — artists who have an undefined place in society, even though they have so much to give.”

One portrait stood out to van Rensburg: that of 102-year-old stone sculptor, Amali Malola. “He never left the village and had never been to the capital, but he passed on his love for the stone to his wife and daughter. He would caress the stone, even though he was almost blind,” says van Rensburg. “He died last year, and was for the first time recognized as one of the greatest sculptors. He even had an exhibition at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe.”

A strong woman, showcased

In 2013, Josh Mojica waited for hours to have his portrait taken when INSIDE OUT’s photobooth truck stopped in New York’s Times Square. Three years later, the flight attendant and photographer read about the Syrian refugee crisis — and decided to take action. He flew to Thessaloniki, Greece, with a mission: to listen to refugees’ stories, take their portraits, and return with posters for pasting. While there, he met Amel, a Syrian refugee nicknamed “Strong Woman” in her camp. Initially, she wasn’t interested in being photographed. Mojica convinced her, and he thinks she said yes mainly because she didn’t expect to hear anything about it again. “When you go to a refugee camp,” says Mojica, “people assume you’re not coming back.”

He returned six weeks later with Amel’s portrait, and she was floored. She asked another woman to watch her children and joined Mojica to paste the poster in downtown Thessaloniki. “It was amazing to watch her fearlessly plaster her own and others’ faces on the walls of a city where she’d been seeking refuge in for over a year,” says Mojica. “It made her feel important.” This experience was powerful for him, too. He has since made 11 more trips to refugee camps in Greece and Serbia, photographing refugees for a project called, “The Struggle Is Real.” He’s taken about 500 portraits so far, and in addition to displaying them locally, he holds exhibitions in the US. “The goal is to help people see refugees as individuals fighting for a better life,” he says.

The homeless get noticed

Photographer Jerry Cordeiro never noticed how many of his fellow citizens in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, were homeless — until he started a Humans of Edmonton Facebook page in 2014. “I started talking to them and listening to their stories,” he says. “They were former professional boxers, lawyers, family men and women. Something just changed in their lives that caused things to spiral out of control.”

Cordeiro launched an INSIDE OUT action, and in May 2016, pasted up portraits of homeless men and women in the city. The impact was instantaneous. “People loved seeing themselves up [on the walls],” he says. “Many of them had not had a photo taken in years.” City residents started showing a genuine interest in those pictured. “People walking downtown to work have stopped and said hi to them by name instead of just ignoring them,” says Cordeiro. The site where he pasted became the backdrop for a temporary pop-up store supporting the homeless population. “Clothing and food was delivered to those that need it,” he says. “People have even bought bus tickets for others to see their long-lost families.”

The eyes of a dreamer

While INSIDE OUT has taken on a life of its own, JR continues his own work. In September 2017, he unveiled two installations across the US-Mexico border. The first showed a one-year-old named Kikito, peeking over the side of his crib — only his image was 40 feet tall and he was peering over the wall separating Tecate from San Diego. Kikito’s family was excited to see his image go viral in September. It resonated deeply in a moment when the wall has become a charged symbol, and Kikito’s mother said it was helping them reclaim their identity from the fray. “She told me, ‘I hope in that image they won’t only see my kid. They will see us all,’” JR told the New Yorker.

Then, in October, JR held a “Giant Picnic” with people on both sides of the border wall talking and sharing food through the slats. Everyone sat around a long picnic blanket printed with an image of a woman’s eyes. Those eyes belong to Mayra, 32, a so-called “dreamer” whose mother crossed into America 28 years ago when Mayra was a toddler. “I was born with a lazy eye,” says Mayra, who still lives in the US. “It was only a few years ago when I received DACA and got a job that offered health insurance that I was able to get surgery to open my eyelid.”

Mayra and her mother attended the picnic, and Mayra says seeing so many people gathered on her eyes made her feel … seen. “People embraced me in their arms, one after the other, and they shared their migration stories,” she says. “My mom told her story for the first time to people outside of our family. I came back feeling a greater sense of responsibility to stand up for who I am. For 25 years, I have lived a reality that feels like a dream — I traveled, I attended college, I dated, I went to the movies. In any of those 9,125 days, I could have been detained and deported. The ‘dreamer’ label is a reminder of that.”

The coal miner’s daughter

In the documentary, Faces Places — now showing in independent theaters in the US — JR road-trips across the French countryside with Agnès Varda, the French New Wave film director. As they pass lavender fields and sing along to “Ring My Bell,” they stop at French villages — some thriving, some declining — and paste up residents’ portraits. A farmer’s photo becomes larger than life on his barn; a group of dock workers’ wives are transformed into totem poles on a sky-high stack of shipping containers. In a celebrity-soaked world, it’s a celebration of everyday people — like so much of JR’s work.

In one of the most powerful moments in the film, JR and Varda visit Jeanine, a coal miner’s daughter in the town of Bruay-la-Buissière. She describes herself as the “sole survivor” on a block of rowhouses now slated for demolition. “They won’t throw me out,” says Jeanine. “I have too many memories here.” JR and Varda bring the block back to life with vintage photos of the workers who once lived here, pasting them up in neat lines — as if they were reporting once again to work at the mines. JR places Jeanine’s face on her building, marking it as hers. When she sees her image for the first time, her hand flies over her mouth. “I don’t know what to say,” she says, and cries.

You can find more images and stories in JR: Inside Out, from Rizzoli Publications, or you can also participate in the Inside Out project.