News flash no. 1: “balloon art” is not an oxymoron. News flash no. 2: The man who invented the Fly Guy, that ubiquitous flailing balloon figure, is crafting some eye- and wind-catching pieces of balloon art. Take a look at these colorful creations from Doron Gazit.

Even though you may not know it, you’re probably familiar with the work of environmental artist Doron Gazit (TEDxVail: Sculpting the winds of change). Every time you walk by a car dealership or supermarket and see a balloon person bending comically in the air, you’re viewing a copy of a Gazit original. In 1996, the Israeli native was tasked to build an installation for the closing ceremony of the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, something that would excite and surprise audiences. The result was the electric fan-powered Fly Guy, a product that’s become an American advertising staple.

Today Gazit regards his most famous invention as “air under the bridge,” but its popularity supports the belief that has driven Gazit’s professional and artistic careers: humans are fascinated by balloons. When he was an industrial design student at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy, he helped pay his tuition by making and selling twisted balloon figures on the street. While he continues to construct elaborate inflatable attractions for tradeshows and big events like the World Cup and the Super Bowl with the company he founded, Airdd, he has also spent the last 30 years whipping up glistening wind tunnels and glowing tubes of light to draw people’s attention to the wonders — and abuses — of nature. “I’m looking for surfaces that tell a story and can be used as a canvas,” he explains. Here, he guides us through a photographic survey of his work.

Start with simple splashes of color

While in design school in the 1980s, Gazit took small latex balloons with him to the Judaean Desert in Israel, a beautiful, natural spot where he enjoyed creating wind art. This image shows some of his earliest work: bouquets of old-fashioned round balloons bloom from a salt formation near the Dead Sea. He says, “I just wanted to leave a touch of myself, but in a way where it wouldn’t be destructive.” (He removed them shortly after taking the photo.) The colors were chosen on a whim, and almost all of Gazit’s work is driven by spontaneity or a strong feeling, with even the scenic locales frequently selected at random.

Animate an “airbow”

To form this “airbow,” Gazit enlisted a group of students to stand on either side of a ravine in the Judaean Desert and hold up tubes of plastic as the wind was blowing. “At that moment, all the elements were like beautiful pieces of the puzzle that fell into the right place. One end of each tube was open, and the wind was inflating and animating them,” he says. Gazit’s installations are typically a collaborative effort. The plastic resin tubes he uses are heavy and cumbersome, especially when they are 300 feet long and must be stretched across a canyon. While relying on serendipity, projects also require some planning. Carefully choosing the right material — he also uses nylon parachute fabric and spinnaker cloth — is necessary since his work depends on the elements. “Sometimes, the wind can be too strong or there’s no wind at all,” he says. “The surface can be too rough and cut the inflatables.” He acknowledges there’s a bit of irony in being an environmental artist who works with plastics, but he tries to be responsible. “I use my plastic resin many times before I send it back to the manufacturer or local recycling centers.”

Pyramid by the sea

For Gazit, a day without wind is no deterrent — it’s when he can experiment with taller shapes. When the air is still, inflatables can be stacked vertically to form a structure. In this case, a pyramid of 50-foot balloons captures the glow of a sunset on Santa Monica Beach in California. The geometric shape of the pyramid was inspired by Buckminster Fuller, famous for his futuristic structures. While his projects require multiple people to execute, Gazit enjoys working with a group for a deeper reason. “When we are together, we are creating a kind of poetry with nature. Each time it’s different, never the same.”

A quiet dance on the water

In 1998, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Okayama Castle in Japan, the city of Okayama asked Gazit to compose a piece that would complement the elegant, temple-like structure. “I wanted the elements involved to have a simple, quiet dance on the water,” he says. He anchored a rainbow of plastic resin chutes to the bank of the Asahi River, inflating them over the water with electric blowers and PVC pipe. As with most of his projects, Gazit drew upon his industrial design background and technical know-how. “I had to make sure enough air flowed into the tubes and maintain enough pressure so the wind did not turn them into big sails and they fly away.” Here, he also needed to factor in the six-foot difference in water levels of the river between high and low tides. For Gazit, observing how the water and wind interact with the tubes is like witnessing a beautiful battle of the elements. This installation was in place for only two weeks, attracting people who would sit on the banks meditating next to the dancing lines.

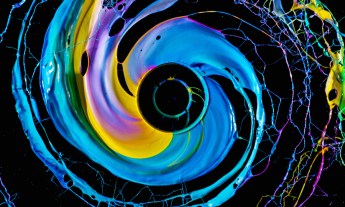

Visualize the invisible

Helpers clutch ribbons of sheer plastic tubing on the crests of the Nitzana sand dunes in Israel. Filled with the desert wind, the tubes act as weightless prisms, absorbing the colors of the sun. This image is from the first Sculpting the Wind installation, which Gazit did when he was a college student. Since then, he has staged similar installations a couple hundred times on different beaches, deserts and cliffs. Unsurprisingly, Gazit — as an artist who works with air and wind — is preoccupied with the unseen. “I’m very much attached to the invisible,” he says. “I call it ‘the in-between’.” He views the human creative process as similar to his shaping of the wind. “When we are inspired by something, it is in our brain and it’s invisible. Then we go through the process of turning it visible, which can be a beautiful poem, story, sculpture or a drawing. Everyone can be inspired in a different way.”

A dialogue between sun and wind

Gazit has been to the Burning Man festival in Nevada eight times, calling it “a fountain of creativity.” He’s built installations on cars and other temporary structures there. In 2012, he wanted to use inflatables to make a connection between science and art. While the black color of the tubes absorbed the heat of the sun, pulling them upwards, the wind inflated them, animating them horizontally. The 150-foot-long tubes floated over festival-goers like two beckoning limbs. Gazit described the end result as “visualizing a dialogue between the elements” of sun and wind. When he sets up his sculptures at Burning Man, attendees gather around him. “Seeing people’s personal experience with the wind, the elements, with Mother Nature — that’s what’s so fascinating and beautiful to me,” he says. “That something so simple can create such a beautiful interaction between human beings and the elements and nature.”

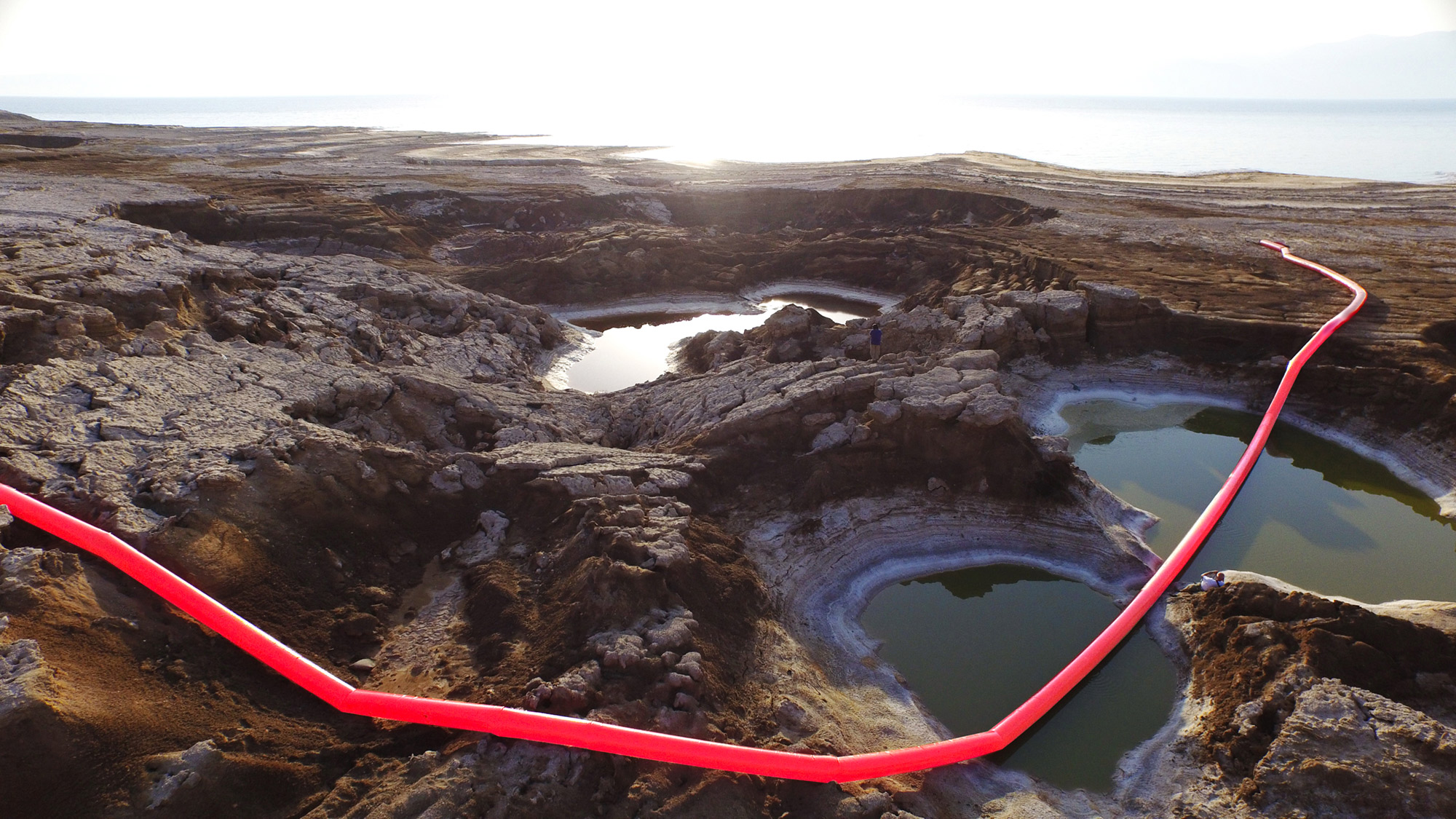

A call to action

Since 2014, Gazit has focused on The Red Line Project, a series of red balloon tunnels — metaphorical stand-ins for the veins of the Earth — winding through damaged areas. He chose the Dead Sea sinkholes in Israel (shown here) as one of the first sites for the project. He’d worked in the area for years and had seen the water recede by three feet every year due to the increasingly hot, arid climate and water mismanagement. As a result, huge holes speckle the sea’s coastline. Gazit says he found himself jolted to channel his art into activism. “When you see this devastation, when you see this happening, how it’s affecting human life, I could not sit still anymore. I knew that I had to rise to action,” he says.

A parched planet

The Red Line Project is not only about climate change, says Gazit; it’s also intended to highlight human misuse of the environment. Pictured here is cracked earth from the Salton Sea, an enclosed body of water that formed in 1905 when the Colorado River flooded California’s Coachella Valley and caused the state’s largest lake. Once an idyllic vacation spot, the lake and its ecosystem have been destroyed by salt pollution caused by agricultural runoff. To sustain water levels, water must flow into the lake and evaporate there, but since the lake has no outlet, the dissolved salt has nowhere to go and dries out the basin. Salt concentrations in the lake have reached 48,000 milligrams per liter, which is 30 percent saltier than ocean water. Because of its increasing salinity and warm — and warming — climate, the lake is shrinking and fish are being killed off. Gazit, who splits his time between Israel and California, regards the Salton Sea as one of his adopted state’s worst ecological disasters.

A line in the water

To work alongside a glacier had been a longtime dream of Gazit’s. “It’s the only place we can see global warming happening in front of our eyes,” he says. In August 2016, he traveled to the Knik Glacier in Alaska and performed a speedy guerrilla installation. With help from family members and fellow environmentalists, Gazit wrangled a boat and sailed near the block of ice. Over four hours, he fed a 500-foot red balloon into the water off the back of the boat, drawing with it on the water next to icebergs that had broken off the glacier. Gazit doesn’t usually wait for bureaucratic approval — he just works fast and leaves. “By the time someone comes to complain or stop me, I’m on my way back home,” he says. Gazit plans to take his project to other locations around the world affected by climate change and human intervention, such as northern Alaska, the Amazon River, Borneo, Sumatra and back to the Salton Sea. He describes the response from viewers as “overwhelming” and hopes his work influences a new generation of nature lovers. “If you are inspired, if you are curious, if you are asking questions of why, how, when, if, what can be done, then your life will be so much more beautiful. You’ll be an inspiration to other people,” he says. “That’s my dream, to inspire other people to make this world better.”

The Red Line project and the Dead Sea sinkholes: Shay Shapira. All other images: Doron Gazit.