“Cookies” and “activism” — those words don’t usually go together. But self-taught baker Jasmine Cho has managed to turn her cookies into canvases to tell deliciously compelling true stories about Asian-American changemakers.

The child of Korean immigrant parents, Cho says she grew up in Los Angeles feeling part of a demographic that was “invisible and narrowly understood.” This feeling came to a head in 2011, when she took a college course in Asian-American history and realized that she’d never heard of a single historical figure mentioned by her professor. “I was born and raised in one of the most multicultural cities in the entire world … but that’s when [I realized] how much it hurt to have been made invisible in the only country I call home,” says Cho.

Around the same time, Cho was getting her online baking business, Yummyholic, off the ground. She originally intended to focus on making “fun and light-hearted” cookies with cheerful images — something like Hello Kitty in baked form. But after that eye-opening history course and her friends began asking if they could have their own portraits put on her cookies, she wondered if there was something more she could be doing with her edible canvases. “I wanted to focus on something that made me feel most alive, that made my heart beat faster, including things that made me angry and frustrated,” she says.

Cho came up with the idea of telling stories through baking — Asian-American stories. She began crafting vivid cookie portraits of significant Asian-American individuals like Olympian Sammy Lee, social activist Grace Lee Boggs, and 9/11 flight attendant Betty Ong — people who haven’t made it into most school curricula in the US. “Privilege,” says Cho, “is when your history is taught as core curriculum while mine is taught as an elective.”

Cho’s goal, is to “bring more attention to Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders who I just didn’t see in media,” she explains. “I wanted to grab people’s attention with my cookies so that they could learn more and realize ‘Oh, I didn’t know!’”

Below is a gallery of her cookie portraits, with stories about each one and how she crafts them.

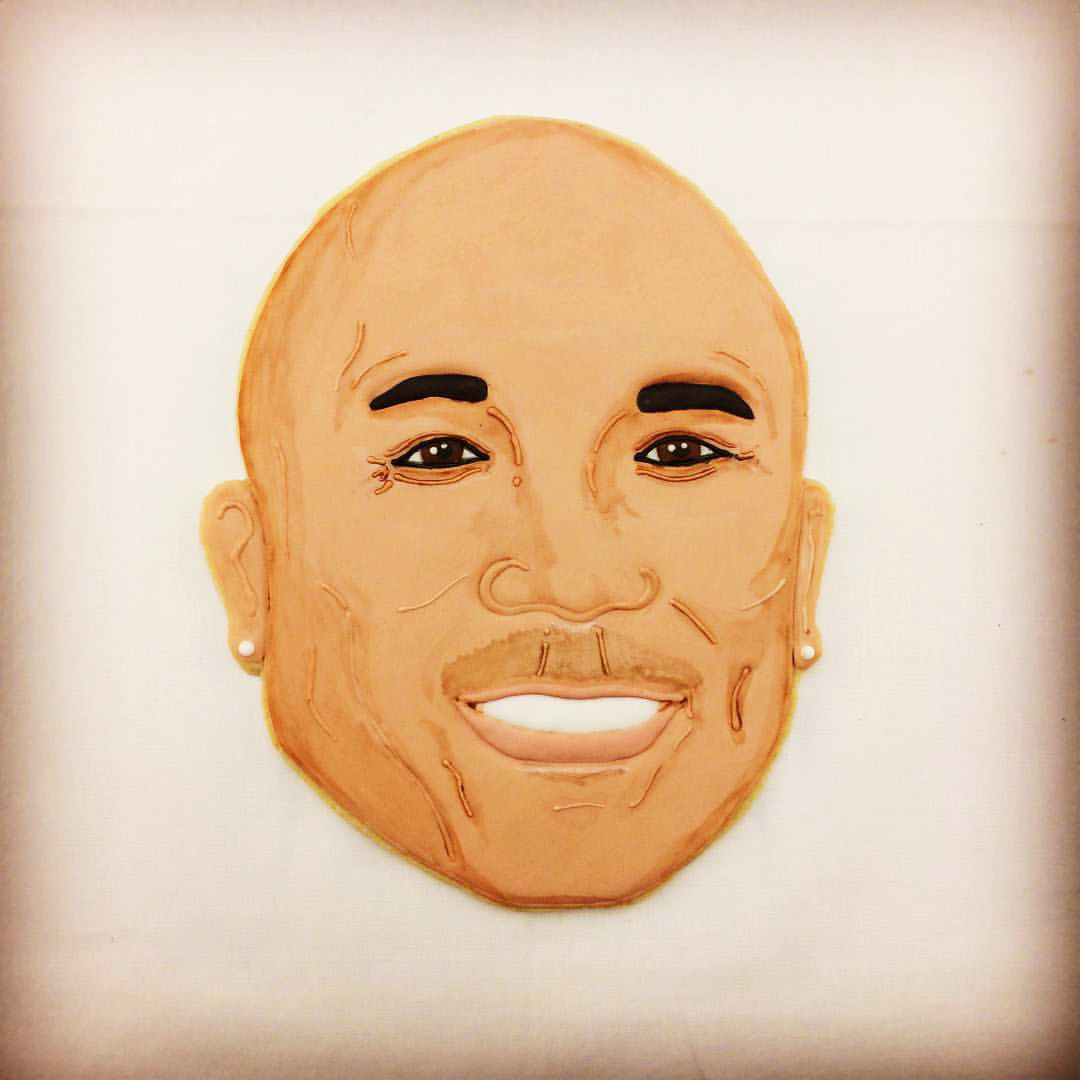

Hines Ward, football player and philanthropist

Ward wasn’t at the market the night when Cho put him on display, but she was able to give him his cookie a year later, in mint condition. “When I do the framed cookies I use Gorilla Glue, so they’re not edible,” she explains, “I let the cookies dry out so they turn rock hard, then I put glue on them and stick them onto a cake board that I mount into a frame.” Ward’s reaction? “He was speechless, with his million-dollar smile,” says Cho. Just like on his cookie.

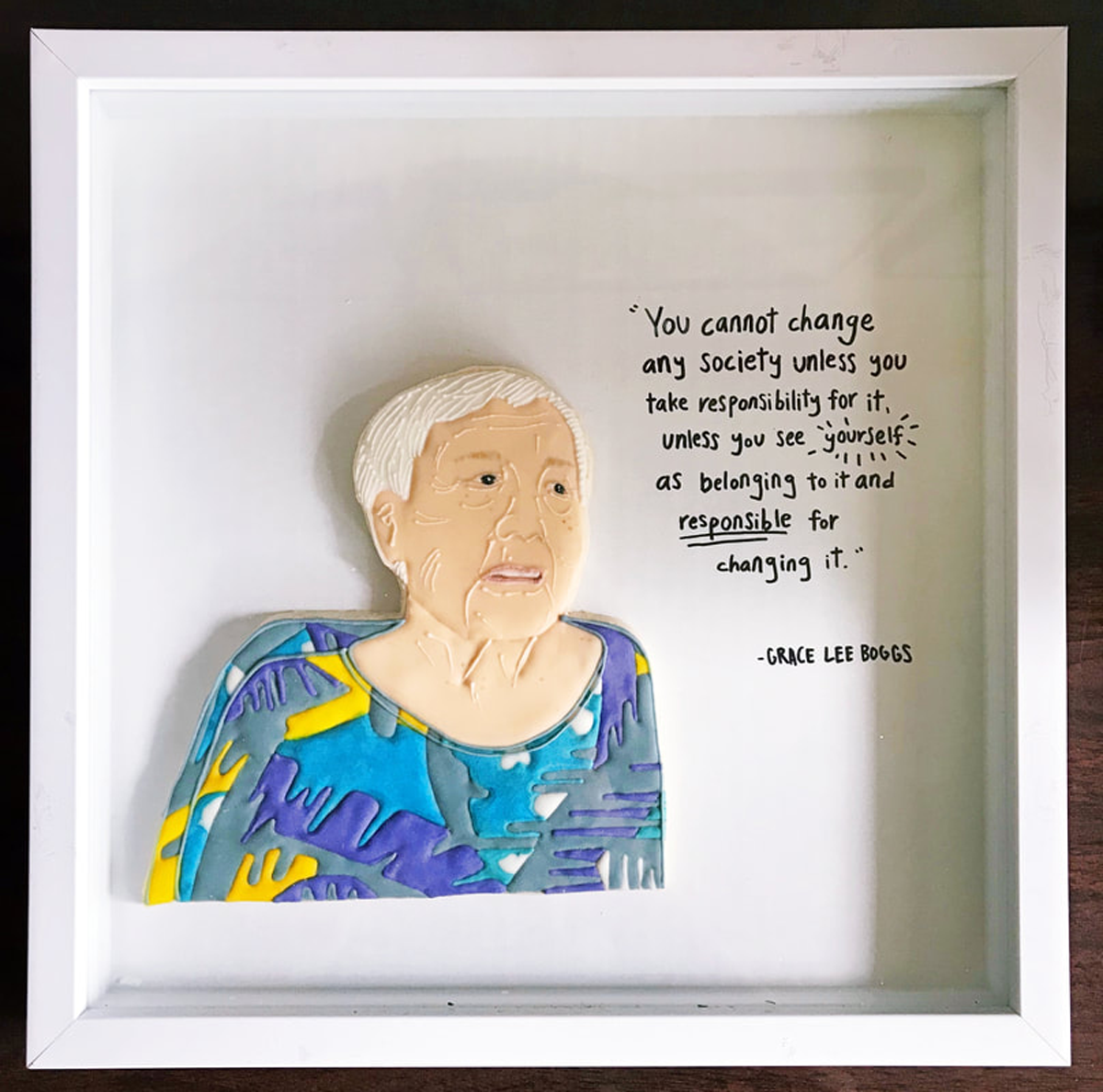

Grace Lee Boggs, lifelong fighter and feminist

Before beginning her baking career, Cho worked as a program coordinator in an elementary school so the cookies she chooses to make are likely to depict Asian Americans typically not covered in lessons in US classrooms. That includes Grace Lee Boggs, a Chinese-American feminist and community activist who lived in the Midwest and fought for civil, social and environmental rights from the 1940s until her death in 2015. Boggs fought for tenants in Chicago at a time when people of color were forced to live in substandard housing, and she established an organization that connected Detroit youth to community service projects. She wrote her fifth and final book, The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-first Century, at the age of 95.

Given the Chinese name Yu Ping when she was born, Boggs married African-American union activist James Boggs in the 1950s and together they focused on community activism, civil rights and the Black Power Movement in Detroit and Chicago. “They were this interracial power couple in Detroit,” says Cho. “That in itself is just remarkable to me.” Referring to modern activism in 2011, Boggs wrote: “We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for.” Cho takes this statement very much to heart. “We’re all part of this history being made,” she says.

Anita Yavich, the “resistance auntie”

Cho’s portraiture encompasses both historical figures and those who embody a current moment or movement. Take her cookie version of Resistance Auntie (based on an illustration from Asian-American artist Shing Yin Khor). “I follow a lot of Asian Americans on Instagram,” says Cho. Two years ago, “[this illustration] was just blowing up on my feed. I noticed it everywhere.”

It’s of Anita Yavich, a New York City-based costume designer and professor whose image went viral when she was photographed protesting Trump’s inauguration in Washington DC in January 2017. “She just happened to be snapped while giving two middle fingers,” says Cho. The community quickly dubbed her “Resistance Auntie,” a name that paid tribute to Anita as an elder and highlighted her defiance of the stereotype of Asians as the “model minority.” Cho framed Yavich’s torso and her defiant two-gun salute with bright, dainty flowers and a banner.

Before baking, Cho wields an X-Acto knife and considerable patience, tracing and hand cutting the person’s outline, then adding a base coat of royal icing (made from a simple mixture of confectioner’s sugar and water with either meringue powder or raw egg whites). Once it’s dry, the royal icing provides a sturdy, glossy surface to which Cho can add finer details. As with all of her portrait cookies, “Resistance Auntie” was made using standard sugar cookie dough. “Using sugar as a vehicle for storytelling is actually very connected to my heritage as a Korean American,” Cho points out. “The first Koreans who came to the Americas worked as laborers on the sugar plantations of Hawaii.”

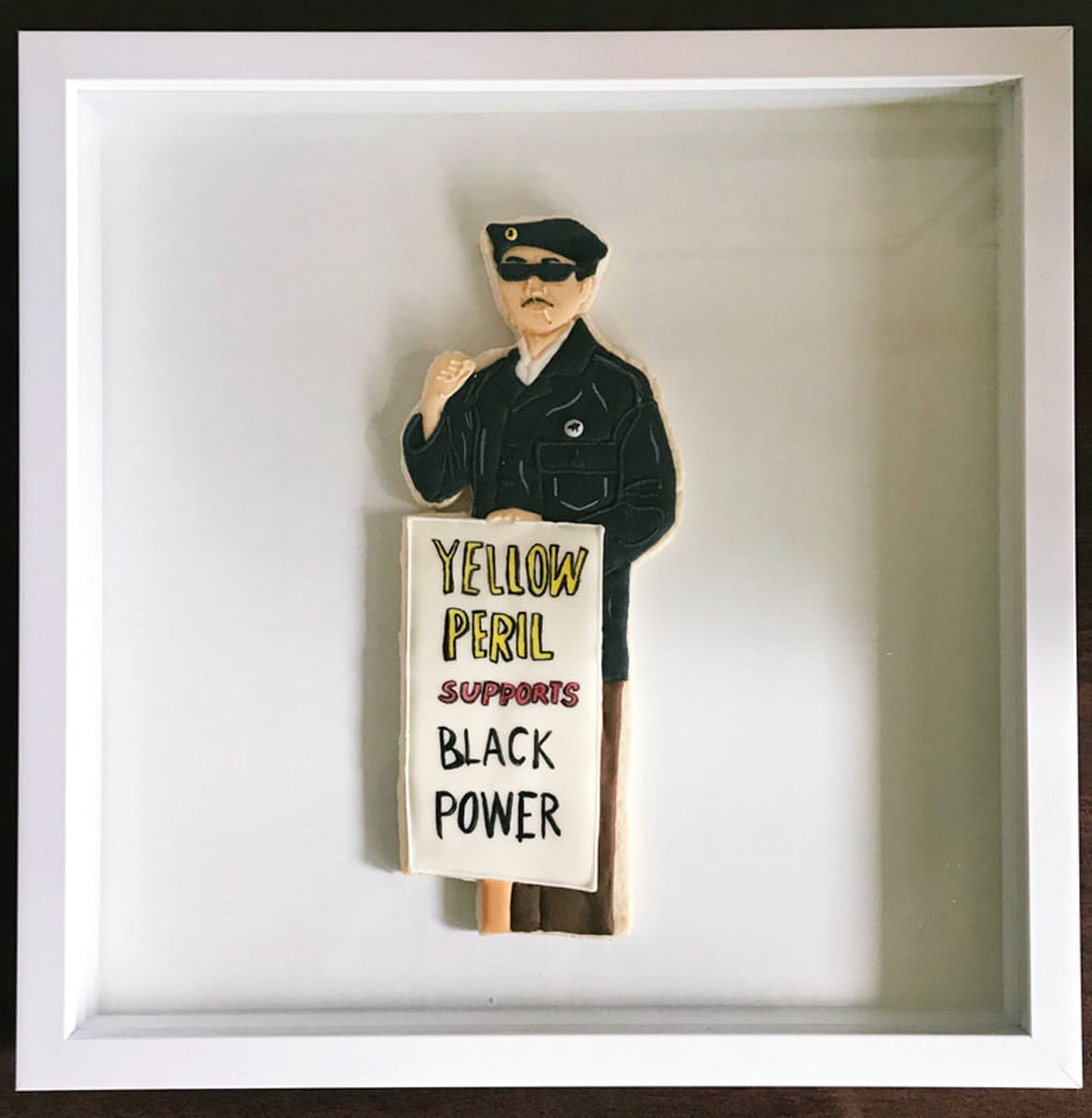

Richard Aoki, revolutionary activist

Overturning the stereotype that Asian Americans are all quiet, hardworking people determined to succeed without disrupting the status quo is a favorite theme for Cho. Japanese American Richard Aoki is perhaps the most controversial cookie in Cho’s portfolio. Aoki was a revolutionary activist who became a Field Marshal for the Black Panther Party in the 1960s; he was later accused of being an FBI informant.

For this cookie, Cho projected his image onto the surface of a cookie (using a palm-sized pico projector), and she painted his hair, skin tone, and clothing. For the paint, she uses food coloring blended with cheap vodka (substituting alcohol for water allows the cookie and icing to withstand the moisture without crumbling). With a tiny paint brush, she lightly shadows, highlights and, when the occasion calls for it, swipes a little blush on the cheeks of each portrait.

As for Aoki’s story, Cho herself isn’t sure what to believe or how to define him, which is why she made him into a cookie. “I’ve heard about two different sides to this person,” she says. “It’s a great reminder that this is who we are as humans.”

Afong Moy, the first Chinese-American woman

In her work, Cho acknowledges earlier Asian American history, as in her rendering of Afong Moy. Moy is believed to be the first Chinese woman known to emigrate to the US. She arrived in the country in 1834, and traders Nathaniel and Frederick Carne labelled her “The Chinese Lady,” exhibiting her as a tiny-footed wonder to gawking audiences up and down the east coast.

Cho relates to this history. “One of the pervasive stereotypes that Asian women face, in particular, is exoticism,” she says. Although not many people today know Moy’s remarkable story, “it set the precedent for how Americans viewed Asian women, and for their understanding of Asian women having tiny feet or tiny features.”

Cho modeled her portrait after the only remaining depiction of Afong, a lithograph of her sitting in an exhibition space. Through this cookie, she is trying to give people an idea of the rich and varied stories — including people like Afong — that exist in and around the Asian-American community. “One of the most powerful forms of civic action is education,” says Cho.

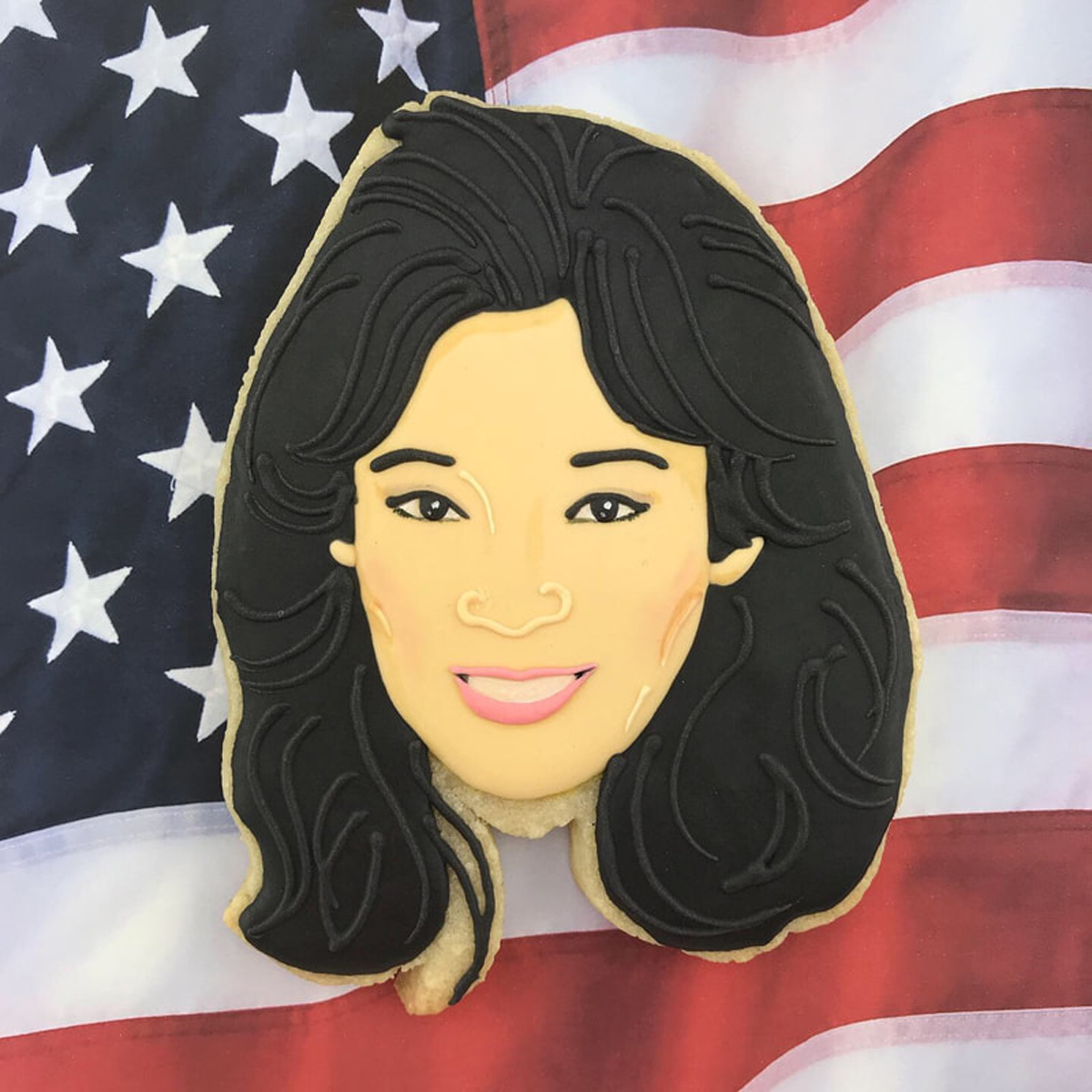

Awkwafina, actor and rapper

Cho’s artwork can be characterized by its clean lines and bold blocks of color, as in this portrait of Chinese-Korean American actor and rapper Awkwafina (whose birth name is Nora Lum). In Hollywood, where Asian and Asian-American actors are often relegated to playing stereotyped roles, “I feel activated by Awkwafina,” says Cho.

So much so that she decided to whip up her cookie portrait when the actress visited a Pittsburgh university in 2018 to discuss mental health, feminism and cultural identity. “She’s just the type of representation of Asian-American identity that I haven’t seen throughout my life,” says Cho. “She’s trying to elevate mental health awareness specifically for the Asian-American community… using her platform to talk about anxiety and issues that are really kept hush hush in the Asian-American community.”

With her multitude of talents and her sense of humor, Awkwafina resists attempts to be fit into a pigeonhole, something that’s true of so many people. “She’s not your average Asian,” says Cho, “At the same time, she is.”

Betty Ong, a 9/11 she-ro

Recently, Cho decided to honor Betty Ong — a 45-year-old Chinese-American flight attendant aboard AA Flight 11 on September 11, 2001 — with a cookie. Ong’s calm and clear communications with airline ground crew immediately alerted them to the hijacking, gave them vital information about the hijackers on board, and caused the FAA to close US airspace. “I want us to remember Better Ong’s name, her face, her courage and resolve, and also her vibrancy and life,” she wrote on a commemorative Instagram post on 9/11 of this year. “She’s one of the she-roes of 9/11.”

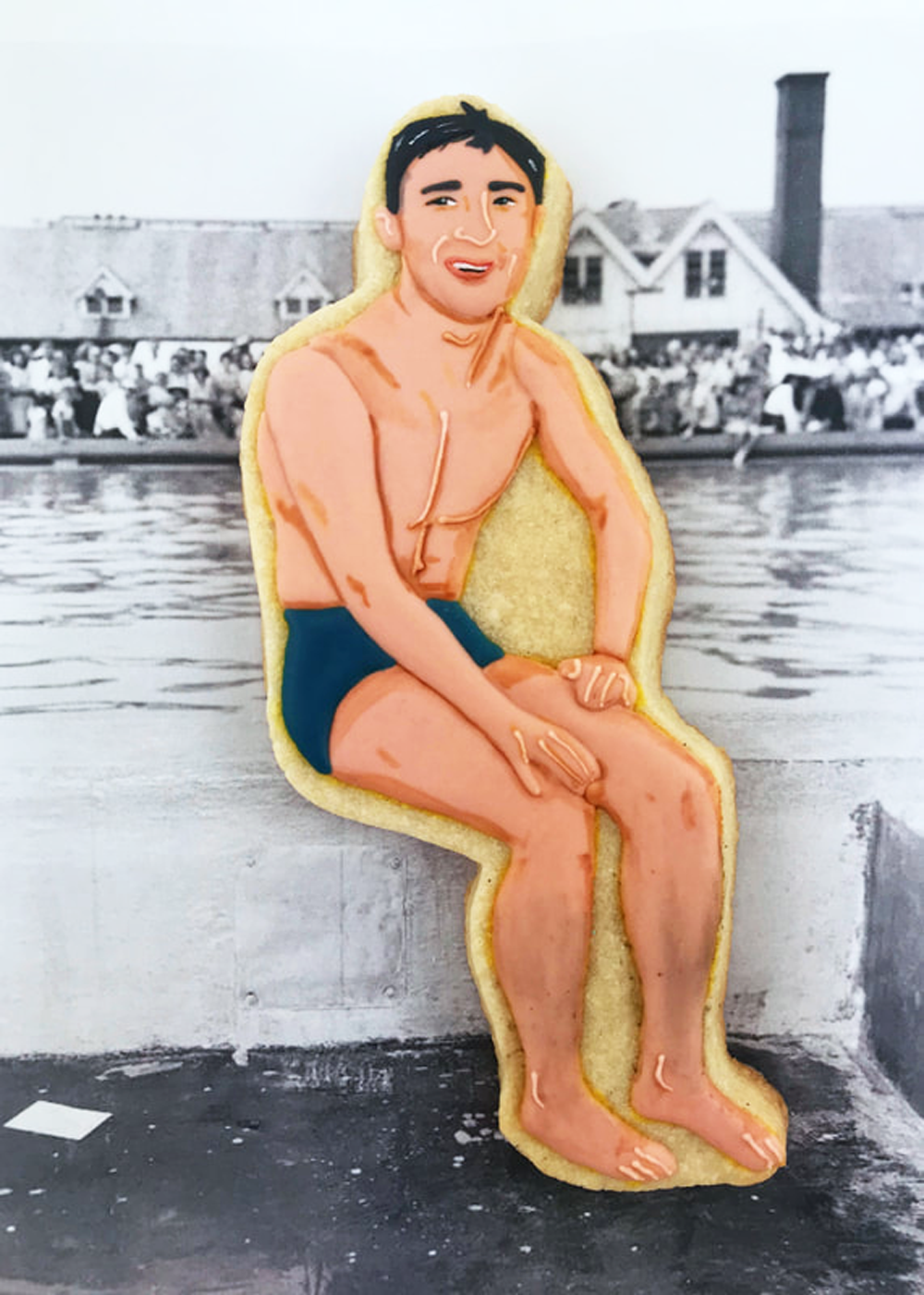

Sammy Lee, an Olympic diver and a doctor

Earlier this year, Cho happened upon a children’s book about Sammy Lee, a Korean-American Olympic diver. In 1948, he became the first Asian-American man to earn a gold medal for the US; he was also the man to win back-to-back gold medals in Olympic platform diving (he won in the 1952 Olympics, t0o). Not only was he a world-class athlete, Lee was also a physician who served in the US Army Medical Corps during the Korean War in the 1950s.

Yet despite his achievements and military service, Lee was a victim of the discriminatory practice of redlining and barred from buying property in white neighborhoods, just as he had been barred from swimming or practicing in public pools as a teenager because he was a person of color. (Instead, hard as it is to believe, he practiced diving into a sandpit that his coach built in his backyard.)

“Sammy Lee grew up in America during the 1930s,” says Cho. “When I grew up in America during the 90s, I learned a lot about the discrimination that happened against the black community, but I didn’t quite learn how that impacted other minorities and communities of color.” She recreated Lee using favorite photo of him, which features Lee with a wide grin, his hair still damp from the pool. “I’m Korean American, how did I never hear about [Sammy]?” is a reaction that Cho hears whenever people see his portrait.

While Cho’s business consists primarily of baking edible cookies, she plans to continue taking the time to create portraits like these. In fact, her next step involves making a lot more of them — for a book of cookie art portraits illustrating Asian American history and also for a stop-motion animated short film that tells the story of the Asian-American diaspora through sugar plantations. Expressing her activism through her portrait cookies “is something that I can literally manage,” says Cho. “It’s like taking one bite at a time. One cookie at a time.”

All images courtesy of Jasmine Cho.

Watch her TEDxPittsburgh talk now: