Photographer Eman Mohammed captures the daily lives of incarcerated women and their children at one of the United States’ rare residential parenting programs.

Eman Mohammed was just 19 when she began covering her native Gaza for a Bethlehem-based news agency. She spent more than a dozen years navigating violence and gunfire — and sexism and harassment — to document the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in order to help others understand its toll on the people living there.

Now living in Washington, DC, Mohammed continues to pursue in-depth projects of what she calls “culturally sensitive communities,” trying to highlight the humanity of people who are often misunderstood. Recently, Mohammed, a TED Senior Fellow, decided to focus on a group of incarcerated women who live with their children behind bars as part of a US government program.

Herself a mother of two, Mohammed went to the Washington Corrections Center for Women (WCCW) in Gig Harbor, Washington, an hour’s drive from Seattle, to find out what life is like for these women, learn how they got there, and show how the program is helping bring hope to them and their young children.

With a child, a second chance

Crystal Lansdale and her son, Kershawn, share a moment while getting ready for the day. Crystal, who came from a poor background, was imprisoned for dealing meth with her partner (he was also incarcerated at the same time). She didn’t know until she went to prison that she was pregnant. Lansdale tells Mohammed, “I grew up feeling like a fugitive, I feared all authority figures and I was constantly avoiding cops. Living with an addict father didn’t scare me away from drugs; instead, I started dealing them. When you’re lost, you turn to what you know, and meth was what I knew. From that point on, my life snowballed.”

Women make up 9.8 percent of the more than 2.12 million people incarcerated in the United States, and many are mothers. Only 12 US prisons allow them to live with their young children in prison. Residential parenting programs were founded to encourage healthy mother-child bonding, promote infant health, teach parenting and work skills, and, hopefully, reduce recidivism.

Of the over 1,000 women held at WCCW, just 8 at a time are allowed into the residential parenting program (RPP) after rigorous screening. They must be minimum-security inmates with sentences of 30 months or less, and they either have babies when they arrive or they’re due to give birth shortly. By being in the RPP, the women avoid having their kids taken from them and placed in the foster-care system — which would have been Kershawn’s fate, says Mohammed. “Governmental institutions are trying to minimize the number of kids who are going to foster homes, which is not an easy, cheap or safe option,” she says. Lansdale adds, “The only time I felt I was given a second chance was when I had my son. I could bond with him, and I started feeling safe. Second chances don’t happen to everyone, so I’m holding on to mine.”

Infancy, in an institution

Cassandra Luthi holds her newborn daughter, Evelyn. She says, “I don’t think people understand how life-changing this is. I’m in prison, yes, but I feel so close to being free. My baby keeps reminding me of that.” Expectant mothers at WCCW go to a nearby hospital when it’s time to give birth, and after they’re discharged, they return to prison with their newborns. Each mother-child pair can stay in the RPP for no more than 30 months. WCCW staff strive to support the special needs and concerns of new moms, including postpartum depression. For example, “designated women known as caregivers are available to help offer a break for a couple of nights if a mother is not getting enough sleep,” says Mohammed.

Determined to stay together

Daidre Kimp adjusts her daughter Stella’s hat before she leaves her for the day. “Daidre was an accountant who was convicted of embezzling from clients,” says Mohammed. “She kind of breaks the mold for what you think is the stereotypical woman in prison — she is well-educated and has a son in college, but she got herself in trouble.” Kimp explains, “Every time I made an amount of money, I needed it to be higher, and my success became tied to a number that was never enough.”

When Daidre entered prison, she was not yet pregnant but she needed to be treated for uterine cancer. She received surgery to remove the growth, then found out she’d gotten pregnant during a prison visit with her spouse. Kimp’s husband is in active duty with the Navy, so he cannot raise the baby by himself. Mohammed says, “At first, he wasn’t supportive of Daidre keeping her baby in prison, but he’s coming around.”

A place where kids can still be kids

Kershawn reads a book with his daycare teacher. “He reads very well for a two-year-old,” says Mohammed. In many respects, life at WCCW is fairly normal for the families. Children and their mothers live together in their own apartments (complete with a lock on the door). After a mom drops off her kid at WCCW’s daycare service, she spends the day in apprenticeship courses and work, such as gardening or cleaning. She picks up her child at the end of the day, and they eat dinner together, followed by a bath and bedtime stories.

Maintaining a normal work day creates a rhythm that’s intended to prepare mothers and children for their future lives, according to Mohammed. “Breakfast is at 6:30 and 7:00, work and daycare begin at 8, and the day ends at 5,” she says. “When the women leave prison and return home, they’ll already be used to a realistic schedule that accommodates work and parenting.”

Gaining skills to succeed

Lansdale carries concrete blocks as part of the Trades-Related Apprenticeship Coaching (TRAC) program, a WCCW course run in partnership with local unions. “TRAC trains and certifies women in construction skills, which will make them employable when they get out of prison,” says Mohammed. “It involves a lot of hard physical training, as well as skills training,”

Women in TRAC are also required to show discipline and leadership skills, and any displays of bad behavior — including bullying, harassment and a lack of initiative — will cause them to be ejected from that program. If successful, each trainee will leave prison with a certification and “preferred entry” for union apprenticeships. “It’s a fairly high starting wage, about $27 an hour,” Mohammed says. “More importantly, not a lot of employers would hire ex-felons.”

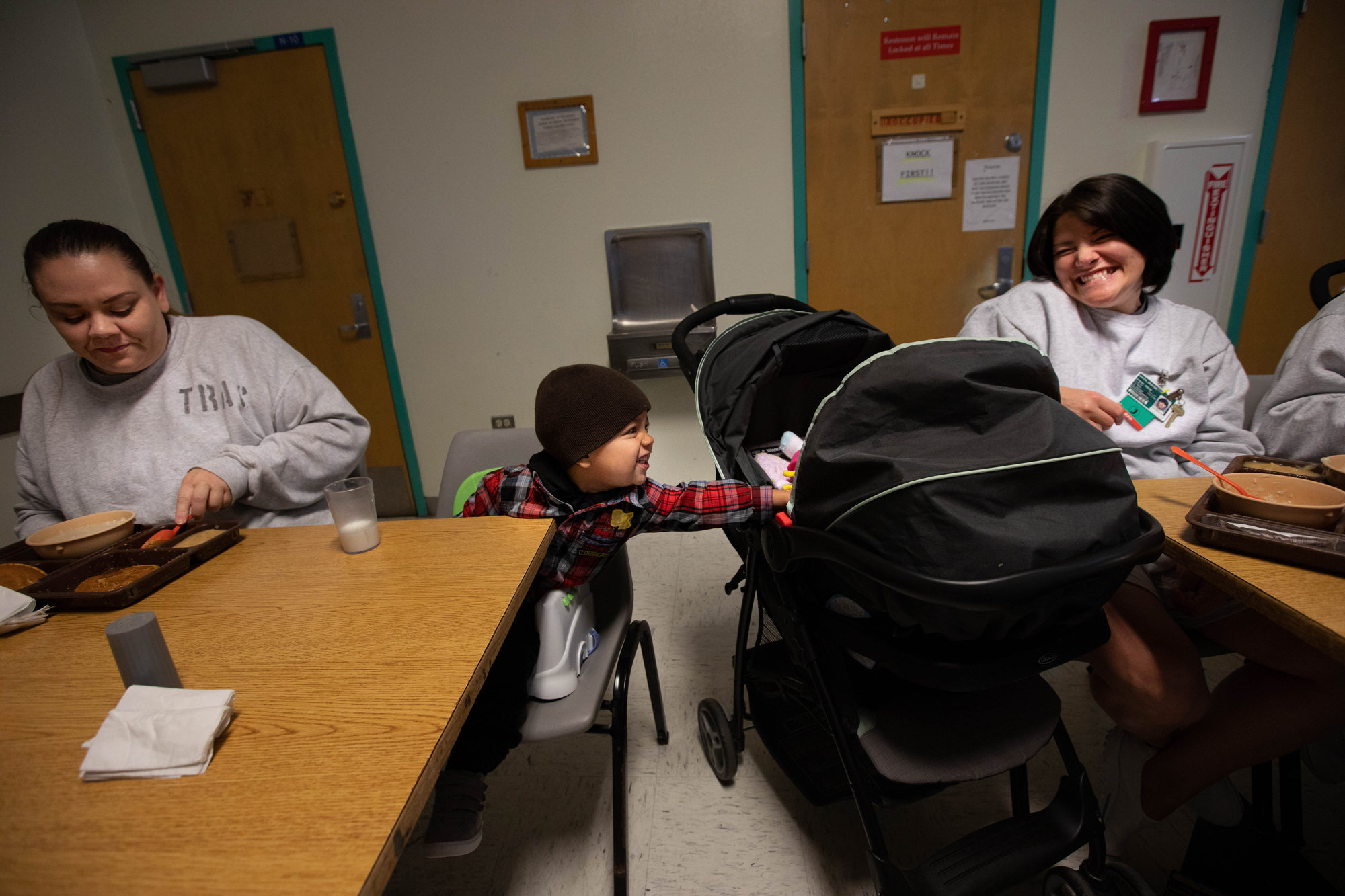

Sharing meals — and a life — together

During breakfast, Kershawn plays with a newborn in a stroller next to him. Children are provided with meals while at they’re at the prison daycare, and for “home” meals, mothers purchase and prepare their own food. Sometimes they receive financial help from family members, and they may also get state and federal assistance for low-income women, such as WIC (the nutrition program for Women, Infants and Children).

“I’ve never, in my whole entire life, seen a more well-behaved child than Kershawn,” says Mohammed. “I didn’t think they existed until I met them. He’s very affectionate, he hugs and kisses and loves, and he speaks nicely. He had a very minor tantrum once, but it was so mild. He and Crystal share a bond that you can’t help but see.“

Ensuring that young ones have room to run

Kershawn and his friend play with a sandbox outside the prison daycare. Within the minimum-security facility, their movement is restricted. Kids aren’t allowed to run freely in the prison halls, and they must be carried or contained in strollers. “It’s a safety issue,” says Mohammed. “Kids do get to walk within the daycare center, in outdoor areas, and inside their own apartments.”

The teachers frequently take the kids to visit their mothers and say hello during their lunch breaks. The children are also allowed out of prison on a weekly basis so they can visit with family members. “Grandparents can come pick up the kids on Friday, for example, and bring them back on Sunday,” says Mohammed. “This way, the child maintains bonds with the extended family and they never feel fully imprisoned.”

A friendship formed in adversity

Kimp and Lansdale walk with their babies through the WCCW grounds. The green cottages are where the women live, and the gardens are maintained by the inmates themselves. “It’s a very organized space, very spacious and well looked after,” says Mohammed. “It doesn’t have the look of a prison.” These two women have become good friends, according to Mohammed. “What landed each of them in the system is very different. They don’t have many interests or desires in common, but they have a bond.”

Being the best mom she can be

Lansdale lies in bed with her son Kershawn at bedtime. “Books are always available in the facility,” says Mohammed. People donate them, and mothers can buy books. There’s a lending library, too. She adds, “Of this picture, Crystal said to me, ‘I’ve never been the the type of mother who reads a bedtime story.’ It’s not that she’s a bad mother, but before she got to WCCW, she wasn’t that equipped to function well. Now, with Kershawn, she feels like she’s really been able to bond properly.”

Mohammed believes their bonding is due in part to the support they’ve gotten at the RPP. She says, “When you’re a new mom — and I speak from experience — you’re constantly doubting and questioning yourself. Having someone there to tell you that you’re doing things right and that things like bonding with a baby is often not instantaneous reduces the emotional and mental burden.”

Looking at the outside world, and the future

Charlee waits for her mother, Katie Hamilton, to come pick her up from daycare. Charlee spends every weekday there while her mother is in TRAC. Only about 10 percent of the women who complete the RPP end up committing crimes and returning to prison, and Mohammed attributes this high success rate to the holistic approach to care. “There were moments when I wished there had been such support for myself as a single mother,” she says. “No one would wish to be in prison, but if we were to take care of all women in society this well, far fewer women would end up in desperate situations and making bad decisions in the first place.”

She adds, “We all make mistakes, visible and invisible, against the law or not. I was so moved by these women’s intelligence and resilience. It’s hard work to fix your own mistakes, and they have to face up to them on a daily basis. That should be respect-worthy, regardless of the crime committed. Society is much harsher on women than men, and for that reason this program is amazing. It tells women they are family enough on their own, that they are not alone, and it gives them all the tools they need to succeed. That’s huge for any mother.”

All images courtesy of Eman Mohammed.

Watch her TED talk now: