Photojournalist Anastasia Taylor-Lind went to Bangladesh to help document the Rohingya refugees fleeing violence and persecution in Burma. Here’s what she saw.

In eastern Bangladesh, where there once were verdant green slopes covered with trees, there is now bleeding red earth. “As far as you can see, the rolling hills have been deforested,” says photojournalist Anastasia Taylor-Lind, who travelled to the city of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, in early October. The hills have been cleared for thousands of makeshift tents that house hundreds of thousands of people who have made a desperate, dangerous journey there in search of safety.

These refugees are Rohingya, a mostly Muslim minority in their home country of Burma. The Burmese military, who refer to the Rohingya as “Muslims” or “Bengalis”, claim they are “terrorists” and are currently targeting them; more than 200 Rohingya villages on the west coast of Burma have been burned down by the country’s troops since the end of August and perhaps thousands of Rohingya have been killed or injured. More than 600,000 Rohingya refugees have fled to Bangladesh to escape this violence in the last two months alone, according to the United Nations. “The number of people fleeing over such a short time is almost unprecedented,” Taylor-Lind says. “This refugee camp is growing day by day.”

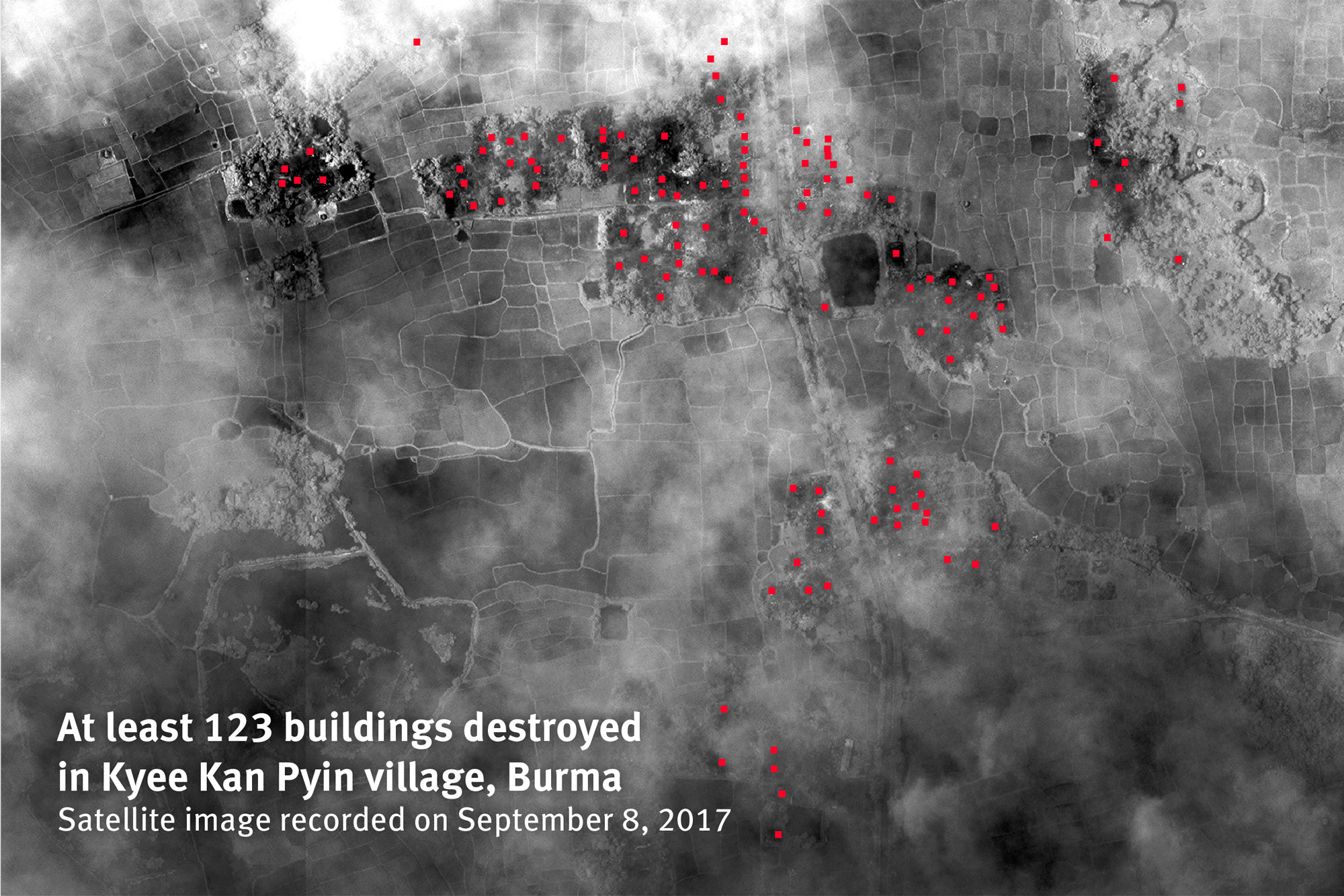

Taylor-Lind, a London-based TED Fellow, went to Bangladesh on a fact-finding mission with Human Rights Watch (HRW), which is investigating and documenting what they’ve labeled ”crimes against humanity” by the Burmese security forces against the Rohingya people. Because the Burmese government has blocked access to the country for journalists as well as humanitarian aid organizations, HRW is collecting the stories of massacre survivors at the camps in Bangladesh, as well as using satellite images to measure the destruction in Burma. “My job is to find a way to visualize what is happening there,” Taylor-Lind says. “The majority of my time is spent making portraits of survivors who are here in exile in Bangladesh and have given eyewitness testimony.”

HRW Emergencies Director Peter Bouckaert, impressed with the portraits Taylor-Lind made in Kiev during the 2014 revolution in Ukraine, hired her to take photographs of the Rohingya refugees — images that will accompany his group’s investigation. “Our work at Human Rights Watch is not just about documenting the horrors,” Bouckaert wrote in an email to TED. “Just as importantly, it is about trying to stop the killings while they are still going on. We can’t do that with words alone: powerful photography is central to what we do.”

This conflict appears to be built on centuries of ethnic tension between the Rohingya Muslim minority and the Buddhist majority in Burma (which is also called Myanmar). The current crisis began on August 25, 2017, when a Rohingya militant group staged a series of attacks on a military camp and 30 Burmese security outposts. In retaliation, HRW reports that Burmese security forces began to commit massacres in Rohingya villages in northern Rakhine State, which borders the Bay of Bengal to the west and Bangladesh in the north.

Eyewitness accounts detail these atrocities, and satellite images show that after the Rohingya were driven from their homes, the Burmese military burned entire communities to the ground. While the Burmese government contests the international media’s depiction of the current crisis, human rights organizations worldwide have condemned the actions of the Burmese military, and the United Nations has deemed their actions “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

“I photographed children with machete wounds to the head and many young men with multiple bullet wounds, and children also,” says Taylor-Lind, who has shared a number of her Rohingya portraits on Instagram. “I’ve photographed women and children who’ve arrived here with horrific burns, and women who’ve had their children murdered in front of them — beaten to death, and in some instances, their babies pulled from their arms and killed in front of them.”

Most of the Rohingya who have survived the massacres flee Burma at night and cross the Naf River in groups to reach Bangladesh. Bangladeshi border guards then escort the refugees to loosely defined camps, where, Taylor-Lind says, “they are loaded off a truck on the side of the road and left there.” Food and water are scarce, she reports, and with few latrines, the sanitation conditions are desperate. Medical care is insufficient, and due to the fact that it’s the middle of monsoon season in Southeast Asia, there’s frequent flooding and lots of mud. Most people live on the bare earth under makeshift tents made from black plastic sheeting held up by bamboo poles. “It’s a pretty dire situation,” Taylor-Lind says. “People are destitute, hungry, traumatized, and often hopeless. I have never seen anything like this before.”

At the camps, Taylor-Lind made dozens of portraits of Rohingya men, women and children who had survived massacres in their village. After a refugee was interviewed by HRW, Taylor-Lind would ask the survivor through a translator, “Can I make your picture? Can I show it to people? Can I tell your story?” The refugee sat as Taylor-Lind tested the light, composed the shot and adjusted the aperture, while the translator held the reflector. “I talk out loud while I’m working, and explain everything I’m doing,” she says.

The portrait sessions, which lasted about 30 minutes each, tended to be quiet. “I wanted to create an atmosphere like a church or mosque,” Taylor-Lind says. “I wanted to reduce the clutter and clamor of the camp in the hopes that I might glimpse a moment in which their experience passed across their face — in the way they looked or the way they looked at me — and show what I cannot photograph.” When she finished, she’d show the survivor their image in the back of her camera. Later, she had the portraits printed at a local shop so she could give each subject a photograph they could keep.

“Most people don’t have photographs with them, because they leave their home with nothing,” Taylor-Lind says. “Most people don’t have photographs of anyone they lost. Can you imagine that? To not have a photo of someone who died? To only be able to rely on your memory to know what their face looked like?”

Taylor-Lind sees these portraits as a collaboration with the survivors — an opportunity to give the Rohingya, after losing so much, a voice. “I don’t think these are necessarily my pictures,” she says. “This isn’t just my picture of Rashida; this is a picture we made together. It’s a collaboration.”

After 26 days at the camps, Taylor-Lind is back in London, editing the photographs she took in Bangladesh. Beyond raising international awareness about the crimes being perpetrated in Burma, she hopes that her portraits, in conjunction with the testimonies collected by HRW, might one day provide evidence of those crimes — the first time her work would be used for such a purpose. “It is important that those who are responsible for these crimes are held accountable,” she says. “And when that happens, this evidence, these testimonies and these photographs may be able to contribute.”

Taylor-Lind also hopes that, in a small way, her portraits might help reaffirm the humanity of Rohingya survivors who are, for now, living in the mud in Bangladesh. “What struck me so much about working there was people’s willingness, their desire, to be photographed,” Taylor-Lind says. “This is ethnic cleansing, and I am photographing the people who survived. Maybe a photograph is proof of life, in some way.”